IJCRR - 13(13), July, 2021

Pages: 162-167

Date of Publication: 05-Jul-2021

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

Identifying Risk Factors for Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

Author: Rohit B Gadda, Keerthilatha M Pai, Yogesh Chhaparwal

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Introduction: Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) encompass several entities, which may have differing etiologies Aim: To identify risk factors for painful TMD among the Indian population presenting to the dental outpatient. Methodology: Subjects with Painful TMD were classified into one of the following three groups: Group 1 (n=24): myofascial pain only, Group 2 (n=38): arthralgia only and Group 3 (n=41): myofascial pain and arthralgia. Forty-one subjects were included in the asymptomatic control group. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) were calculated from multiple logistic regression models that included the relevant risk factors. Results: Increased risk of myofascial pain with arthralgia was significantly associated with clenching (OR: 7.9, CI: 2.1-30), trauma (OR: 12.3, CI: 2.1-69.9), third molar extraction (OR: 3.7, CI: 1.1-12.6), and nonspecific physical symptoms (NPS) with pain (OR: 8.1, CI: 1.8-35.4). Increased risk of myofascial pain only was associated with clenching (OR: 5.5, CI: 1.3-23.3), trauma (OR: 13.2, CI: 2.2-77.5), and NPS with pain (OR: 6, CI: 1.3-26.7). Increased risk of arthralgia only was associated with trauma (OR: 9, CI: 1.8-45.4). Conclusion: A high proportion of subjects with painful TMD reported having clenching, trauma, NPS with and without pain, and depression.

Keywords: . Key Words: Temporomandibular disorders, Risk factors, Myofascial pain, Arthralgia, Clenching

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a collective term embracing several clinical problems that involve the masticatory musculature, the temporomandibular joint and associated structures, or both. Signs and symptoms of TMD have a higher incidence in the general population (20–75%) than the proportion of the population who present for treatment (2–4%).1

Painful TMDs are classified into the Myofascial pain group and Arthralgia group according to Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD).2,3, 4 The aetiology of TMD remains unclear, but it is likely to be multi-factorial. Five major factors associated with TMD are occlusal factors, trauma, emotional stress, deep pain input and parafunctional activities, but these have been the subject of much debate.

G J Huang et al.2 investigated risk factors for three diagnostic subgroups of painful TMD in Washington. Their study consisted of 97 subjects with myofascial pain only, 20 with arthralgia only, 157 with both myofascial pain and arthralgia, and 195 controls without painful TMD. Trauma, clenching, third molar removal, somatization, and female gender were identified as risk factors for subjects with myofascial pain as well as for subjects with concurrent myofascial pain and arthralgia. Analysis of various risk factors associated with subgroups of TMD has been carried out in various studies mostly in the western population. Several studies have categorized painful TMD into subgroups like myofascial pain, arthralgia and concurrent myofascial pain and arthralgia.2, 5-8

Since TMD is a common complaint of patients attending dental outpatients, knowledge of risk factors is useful in the management of the condition. Thus, this study aimed to investigate risk factors for the diagnostic subgroups of painful TMD among the Indian population presenting to the dental outpatient. The objectives of the study were to determine the prevalence of various subgroups of painful TMD, to describe the demographic characteristics of patients with painful TMD, to describe various risk factors associated with painful TMD, and to identify risk factors that are more frequently associated with painful TMD.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This study was carried out in the department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, of a dental hospital. Approval to carry out this study was obtained from Institutional Ethics Committee (Letter No.: IEC 146/2008). All subjects in this study were recruited from the dental outpatient department and enrolled for the study after obtaining informed consent. A total of 14,287 patients visiting dental outpatient was screened and those reporting pain in the jaw muscles or the joint in front of the ear or inside the ear (other than ear infection) were enrolled as cases (n=103) after satisfying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Concurrent controls (n=41) were selected from the same outpatient department. They may have come to the dental clinic for a variety of reasons including cavities, periodontal disease or preventive maintenance, but with no pain in the jaw muscles, temporomandibular joint (TMJ), or inside the ear. Inclusion criteria for cases were patients with pain in the jaw muscles, the joint in front of the ear or inside the ear (other than ear infection) and patients who agree to sign informed consent. Exclusion criteria for cases were the presence of polyarthritis or another rheumatic disease, patient with trauma to jaws with clinical suspicion of jaw fracture, patients with a previous history of temporomandibular joint surgery, patients having pain in the jaw muscles or TMJ region attributed to pathology other than TMD.

All subjects underwent an interview using a standard history questionnaire form (modified from RDC/TMD) by a trained examiner. Information on risk factors was obtained by asking questions that required dichotomous answers (Yes/No) as follows: History of Parafunctional activity like clenching or grinding of teeth, Facial trauma with no jaw fracture, Recent dental treatment, Third molar removal, Orthodontic treatment, and Unilateral chewing. Patients were asked to report subjectively whether they consider themselves as being stressed all the time, most of the time, sometimes, rarely, or never. The psychosocial assessment was carried out by administering a scale of SCL-90 as described in the RDC/TMD. Depression, nonspecific physical symptoms (NPS) with pain items included and NPS with pain items excluded were measured.

EXAMINATION

All subjects underwent detailed TMJ & intraoral examination. Examiner calibrated his finger pressure for palpation of joint and muscles using a pressure algometer. The standardized pressure recommended by RDC/TMD was followed. TMJ examination was carried out according to specification by RDC/TMD. Intraoral examination was performed to note details of missing teeth, root remnants and molar relation. The occlusal condition was classified using Eichner’s index.

Depending on the data collected, cases were classified into three groups of painful TMD, based on the RDC/TMD: Group 1: One with myofascial pain only. (n=24), Group 2: One with arthralgia only (n=38), Group 3: One with both myofascial pain and arthralgia (n=41). Asymptomatic controls were assigned to group 4 (n=41).

The second trained examiner carried out the standard TMJ examination for 10 painful TMD cases which were already examined by the first examiner. She classified the cases into three groups without prior knowledge of the first examiner’s findings. Inter-observer variation was assessed for these 10 subjects.

STATISTICAL METHODS

The SPSS statistical package for Windows, version 11.5, was used for the analysis of the data. Variables like NPS with and without pain, depression and stress were dichotomized (Yes/No, ‘Yes’ is a moderate and severe level of NPS with & without pain, depression, and presence of stress, whereas ‘No’ is the normal level of NPS with & without pain, depression, and absence of stress). The occlusal condition was dichotomized as ‘Eichner’s class A’ and ‘Eichner’s class B & C’. One way ANOVA was used to check any difference in age between all groups. The Chi-square test was used to analyze any difference between groups with gender, education, marital status, and various risk factors. The p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Association between study groups and risk factors was expressed using an unadjusted odds ratio (OR) and a 95% confidence interval (CI). If 95% CI includes one, then the odds ratio is not significant. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) were calculated from multiple logistic regression models that included the relevant risk factors.

RESULTS

A total of 14,287 subjects reporting to a dental outpatient section of MCODS, Manipal was screened for painful TMD, 103 subjects were diagnosed as having painful TMD. The prevalence of painful TMD among the patients visiting the dental outpatient department during one year was 0.72%. Subjects with Painful TMD were classified into one of the following three groups: Group 1 (n=24, 23.3%): Subjects with myofascial pain only, Group 2 (n=38, 36.9 %): Subjects with arthralgia only and Group 3 (n=41, 39.8%): Subjects with both myofascial pain and arthralgia. Forty-one subjects were included in the asymptomatic control group (group 4).

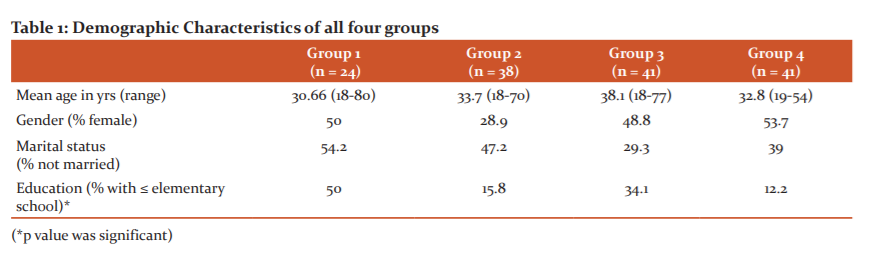

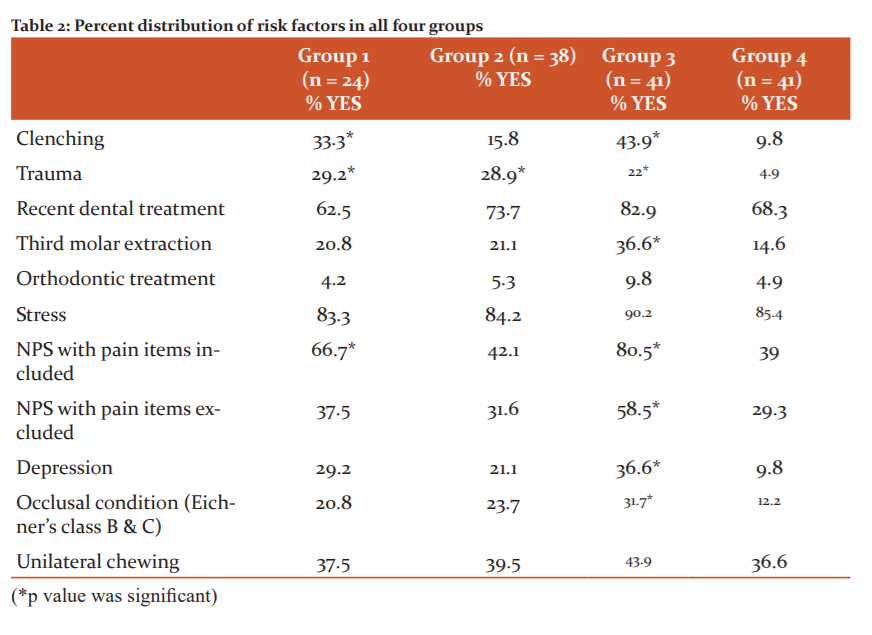

There was no statistically significant difference in the age, gender and marital status of subjects in the four groups (p> 0.05). The high proportion of subjects with painful TMD had education below elementary school (p < 0.05) (Table 1). Table 2 shows the per cent distribution of risk factors in all four groups. A high proportion of subjects with myofascial pain (with or without arthralgia) reported clenching, facial trauma, third molar removal, NPS with and without pain, and depression.

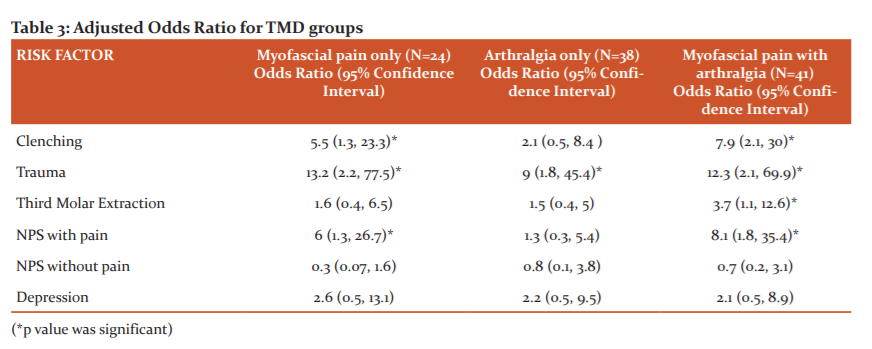

Table 3 shows the adjusted odds ratio for relevant risk factors. In multivariate analysis with simultaneous adjustment for the presence of risk factor, increased risk of myofascial pain with arthralgia was associated with clenching, trauma, third molar extraction, and NPS with pain. Increased risk of myofascial pain only was associated with clenching, trauma, and NPS with pain. Increased risk of arthralgia only was associated with trauma.

DISCUSSION

TMD-related pain is a less common symptom with prevalence estimates in the region of 10–15% worldwide.9 However; pain is the major reason that people seek professional care for TMD. Patients seeking treatment for TMD-related conditions, notably jaw pain and functional disability, represent a small proportion (around 2%) of the general population.10,11,12 Hence our study considers only painful TMD.

The present study was an attempt to determine the prevalence of various subgroups of painful TMD among the patients visiting dental outpatient; and to investigate various risk factors associated with diagnostic subgroups of painful TMD, distinguishing between muscular (myofascial) pain and joint pain (arthralgia).

The prevalence of painful TMD among the patients visiting the dental outpatient department for one year was 0.72%. It was relatively low as compared to previous studies.10-13 This could be attributed to only painful TMD being considered in our study. Also, our study was a single centre study and this centre was an oral medicine speciality clinic and not a TMD pain speciality clinic like in other studies.13,14

There was a higher prevalence of myofascial pain (63.1%) in our study. The most common type of TMD was muscle disorders and agrees with studies in other Western and Asian patient groups.13,15-17Painful TMD groups and controls were similar concerning gender. Results of European, US studies and Asian study12,18 have shown a significant difference between TMD prevalence in male subjects compared with female subjects.

In our study, we did not try to differentiate between clenching and grinding, and a self-report of this habit was noted. A high proportion of subjects with painful TMD reported the presence of a clenching habit. There was an increased risk of myofascial pain only and myofascial pain with arthralgia associated with clenching. These findings were seen in studies by Huang GJ et al.2 and Velly AM et al.19 When the muscles are voluntarily contracted for longer periods, the muscle ?bers start to present fatigue. Muscle fatigue is considered to be one of the causes of pain associated with TMD. The hypothesis of the vicious cycle of cyclic muscle pain helps to explain the association between clenching and myofascial pain.

In our study, a high proportion of subjects with painful TMD reported a history of trauma. This finding of trauma as a risk factor for painful TMD was consistent with that of a study by Huang GJ et al.2 but they did not find any significant association for the arthralgia only group. Velly AM et al.19 concluded that trauma may contribute to myofascial pain. Pullinger20 found that a history of trauma was reported by more than 50% of subjects with disc displacement, or myalgia only.

In our study, third molar extraction caused a significantly increased risk of myofascial pain with arthralgia. This finding was similar to that seen in the study by Huang GJ et al.3 (2002) but they also found third molar removal as risk factors for subjects with myofascial pain only. We did not attempt to assess the temporal relationship between third molar removal and painful TMD. A prospective design would allow for a more definitive assessment of this risk factor.

In our study, there was no significant association seen between TMD and orthodontic treatment. Similar findings were observed in previous studies.2,21

Literature data on TMD supports the existence of an association with several psychosocial disorders, such as anxiety, depression and somatization disorders.22 There is increasing evidence that the complex relationship between psychopathology and TMD could depend upon the presence of painful TMD conditions and not upon the location of the disorder.13 In our study, there was an increased risk of myofascial pain only and myofascial pain with arthralgia associated with NPS with pain. These findings of our study were similar to several studies that have categorized TMD into subgroups similar to those in our study. These studies examined psychological differences between subgroups2,5-8 and generally indicated that patients with myogenic diagnoses had more pain and distress than those with joint-related diagnoses. The psychological distress leads to parafunctional activities (tooth clenching and grinding) that results in muscle pain.23

In our study, the presence of Eichner’s Class B & C occlusal condition caused a significantly increased risk of myofascial pain with arthralgia. This finding was similar to that seen in the study by Takayama Y et al.24 We did not find any association of unilateral chewing and TMD, in contrast to observation by Diernberger S et al. 25

Inter-observer variation was assessed for 10 subjects. Diagnosis using RDC/TMD and classification in the case of a group, by both the examiners were correlated perfectly for 9 out of 10 subjects. John MT et al.26 concluded that the RDC/TMD demonstrated sufficiently high reliability for the most common TMD diagnoses, supporting its use in clinical research and decision making.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of painful TMD among the patients visiting dental outpatients for one year was 0.72%. There was a higher prevalence of myofascial pain (63.1%) in the study groups. A high proportion of subjects with painful TMD reported having clenching, trauma, NPS with and without pain, and depression. Increased risk of myofascial pain only was associated with clenching, trauma, and NPS with pain. Increased risk of arthralgia only was associated with trauma. Increased risk of myofascial pain with arthralgia was associated with clenching, trauma, third molar extraction, and NPS with pain.

Our study had several strengths, including the reliable, criterion-based (RDC/TMD) examination of all subjects; and adjustment for potentially confounding variables. The number of subjects in the study was small and they were from a single centre. Hence, the results of this study cannot be generalized and studies with larger numbers of subjects are needed.

Acknowledgement:

The authors acknowledge the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. The authors are also grateful to authors/editors/publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed.

Conflict of interest and source of funding: Nil

References:

-

Durham J. Temporomandibular disorders (TMD): an overview. Oral Surgery. 2008;1:60-68.

-

G J Huang, L LeResche, C W Critchlow, M D Martin, M T Drangsholt. Risk factors for diagnostic subgroups of painful temporomandibular disorders (TMD). J Dent Res. 2002;81:284-9.

-

LeResche L, Fricton J, Mohl N, Sommers E, Truelove E. Axis I: clinical TMD conditions. J Craniomandib Disord Fac Oral Pain. 1992;6:327-30.

-

Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, a critique. J Craniomandib Disord Fac Oral Pain. 1992;6:301-55.

-

Celic R, Jerolimov V, Panduric J, Haban V. Depression and somatization in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2006;40:35-45.

-

Nifosì F, Violato E, Pavan C, Sifari L, Novello G, Guarda Nardini L, Manfredini D, Semenzin M, Pavan L, Marini M et al. Psychopathology and clinical features in an Italian sample of patients with myofascial and temporomandibular joint pain: preliminary data. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2007;37(3):283-300. doi: 10.2190/PM.37.3.f. PMID: 18314857.

-

Reibmann DR, John MT, Wassell RW, Hinz A. Psychosocial pro?les of diagnostic subgroups of temporomandibular disorder patients. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116:237-44.

-

Manfredini D, Marini M, Pavan C, Pavan L, Guarda-Nardini L. Psychosocial pro?les of painful TMD patients. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;36:193-8.

-

LeResche L. Epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders: implications for the investigation of etiologic factors. Crit Rev Oral Biol. 1997;8:291–305.

-

Goulet JP, Lavigne GJ, Lund JP. Jaw pain prevalence among French-speaking Canadians in Quebec and related symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. J Dent Res. 1995;74:1738–44.

-

Pow EHN, Leung KCM, McMillan AS. Prevalence of symptoms associated with temporomandibular disorders in Hong Kong Chinese. J Orofac Pain. 2001;15:228-34.

-

Shiau YY, Chang C. An epidemiological study of temporomandibular disorders in university students of Taiwan. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20:43-7.

-

Yap AUJ, Dworkin SF, Chua EK, List T, Tan KBC, Tan HH. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders subtypes, psychologic distress and psychosocial dysfunction in asian patients. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17:21–8.

-

Yap AUJ, Chua EK, Tan KBC. Depressive symptoms in Asian TMD patients and their association with non-speci?c physical symptoms reporting. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:305-10.

-

Lee LTK, Yeung RWK, Wong MCM, Mcmillan AS. Diagnostic sub-types, psychological distress and psychosocial dysfunction in southern Chinese people with temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:184-90.

-

Manfredini D, Chiappe G, Bosco M. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (RDC ⁄ TMD) axis I diagnoses in an Italian patient population. J Oral Rehabil. 2006;33:551-8.

-

List T, Dworkin SF. Comparing TMD diagnosis and clinical ?ndings at Swedish and US TMD centers using Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. J Orofac Pain. 1996;10:240–253.

-

Grosfeld O, Jackowska M, Czarnecka B. Results of epidemiological examinations of the temporomandibular joint in adolescents and young adults. J Oral Rehabil. 1985;12:95–105.

-

Velly AM, Gornitsky M, Philippe P. Contributing factors to chronic myofascial pain: a case–control study. Pain. 2003;104:491-9.

-

Pullinger A S, Seligman DA. Trauma history in diagnostic groups of temporomandibular disorders. Oral surg Med Pathol. 1991;71:529-34.

-

Luther F. TMD and occlusion part II. Damned if we don’t? Functional occlusal problems: TMD epidemiology in a wider context. Bri Den J. 2007;202: E3.

-

Sirirungrojying S, Srisintorn S, Akkayanont P. Psychometric pro?les of temporomandibular disorder patients in southern Thailand. J Oral Rehabil. 1998;25:541-544.

-

Vidhya K, G.V. Murali Gopika M. A study of the relationship between stress, adaptability and temporomandibular disordersy. Int J Cur Res Rev. 2016;8(4):01-05.

-

Takayama Y, Miura E, Yuasa M, Kobayashi K, Hosoi T. Comparison of occlusal condition and prevalence of bone change in the condyle of patients with and without temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:104-12.

-

Diernberger S, Bernhardt O, Schwahn C & Kordass B. Self-reported chewing side preference and its associations with occlusal, temporomandibular and prosthodontic factors: results from the population-based Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP-0). J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:613-20.

-

John MT, Dworkin SF, Mancl LA. Reliability of clinical temporomandibular disorder diagnoses. Pain. 2005;118:61–9.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License