IJCRR - 13(7), April, 2021

Pages: 97-105

Date of Publication: 12-Apr-2021

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

Prevalence of Post-Partum Depression and the Associated Risk Factors Among Materials in Al-Madinah City 2019

Author: Khalid Ahmad Amara, Somaya Mohammad Mahfouz Alshereif, Reham Mohammad Kharabah

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Introduction: Postpartum depression (PPD), a type of mood disorder, is the most frequently noted morbidity during the post�partum period. Objective: To investigate the prevalence and assess risk factors of postpartum depression symptom among post-partum mother in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia. Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted on a population of 360 post-partum mothers delivered in the hospitals in Al-Madinah city, from January to February 2019 in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia. Data were collected using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). The data were analyzed with Version 22.0 of the Statistical Package for Social Science. Descriptive statistics, Spearman correlation, Mann Whitney test and Kruskal Wallis test were used. Results: The prevalence of post-partum depression PPD among post-partum mothers was 23%, with a mean score of 9.0\?5.0. Post-partum depression was significantly higher among mothers who delivered at the house, those who had depression during a previous pregnancy and those who had a family history of PPD. (p< 0.05). Conclusion: Post-partum depression was found in one-third of the post-partum mothers who included in the study. Women who had previously been diagnosed with PPD reported a family history of PPD were at particularly high risk for postpartum depres�sion. To prevent and treat postpartum depression, special care should be provided to women reporting risk characteristics.

Keywords: Postpartum depression (PPD), risk factors, Madinah, Saudi Arabia

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Postpartum depression (PPD), a type of mood disorder, is the most frequently noted morbidity during the postpartum period.1 PPD is defined as " in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders as major depression with postpartum onset with episodes of depression beginning within 4 weeks of giving birth"2 It is a non-psychotic depressive state that begins in the post-partum period, after the childbirth, it is a mood disorder that can occur at any time during the first year after delivery.3

PPD affects the health of both the mother and her children, especially mother-child bonding and the relationships among family members.3,4 Several studies have found that risk factors for depressive symptoms are clustered into five main groups: 1.biological, consisting of changes in hormone levels and the age of mother; 2.physical, consisting of chronic health problems and antenatal depression; 3.psychological, consisting of prenatal anxiety, stress, lack of social support and stressful life; 4.obstetrics/paediatrics, consisting of unwanted pregnancy, history of loss of pregnancy and severely ill infants; 5.and socio-cultural, consisting of the status of mother and poverty.3-8 PPD has been associated with catastrophic consequences, such as mother suicide and infanticide.3 Financial shortage, infant gender, domestic violence, hunger, and smoking during pregnancy have been reported as risk factors of PPD.3,4,9

Although PPD is a major health issue for many women from diverse cultures, this condition often remains undiagnosed.10 The use of screening scales is an easy, simple and cost-effective way to identify women who are at risk of depression.1,11 The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is the most widely used screening tool in identifying PPD,1,12-14 and it has been validated and used in many countries, including Saudi Arabia.15

PPD is the most common childbirth complication1 which affects 10%–15% of women in high-resource countries.16 However, the prevalence is also considerably high in developing countries, including India (23%)17, Pakistan (44%)18 and Vietnam (33%).19 In Saudi Arabia studies the prevalence was 33.0%-49.5%.15,20

Post-partum depression symptom represents a common problem among post-partum mother due to several factors. PPD symptoms result from a combination of biochemical, physical and emotional factors. The main biochemical factor causing PPD symptoms is reduced hormonal levels which lead to chemical changes in the brain that may activate mood swings. The researcher has a special interest in depression, particularly among post-partum mothers. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and assess risk factors of postpartum depression symptom among post-partum mothers in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was across sectional descriptive study among post-partum mothers delivered in the hospitals in Al-Madinah city. Post-partum mothers with substances abuse or bipolar major depressive disorder were excluded. The calculated sample size was 360 with 95% confidence limits, 5% accepted errors, the prevalence of PPD syndrome =30%, 3and with 10% (30 nurses) was added to the sample to avoid withdrawing and refusing to participate.

The required sample size was divided equally to cover the three hospitals (National guard, Ohod, and MMCH hospitals) (120 post-partum mothers/ hospital).

Valid structured self –administered questionnaire. The questionnaire is to obtain from previous study 15and it contains three main parts: A – Socio-demographic characters. B – pregnancy and delivery characteristics. C – The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

The dependent variable of the study was the post-partum depression scale. And the independent variables were sociodemographic characteristics and pregnancy and delivery characteristics. Data was entered and processed by using SPSS software version 21 for analysis and interpretation. P-Value is considered statistically significant if it is ≤ 0.05.

The following approvals were obtained: research ethical committee, the supervisor of the general training program, primary healthcare centre PHCC director. Written consent was obtained from each participant. And the collected data was handled confidentially.

RESULT

Normality

The Shapiro-Wilk statistic test was done for the following continuous variables Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDs score, age, children number, labour duration, and gravidity).The result were (0.906, 0.983, 0.925, 0.583, and 0.95) with (p<0.001, p<0.001, p<0.001, p<0.001, and p<0.001). Indicating non normally (non-parametric) distributed.

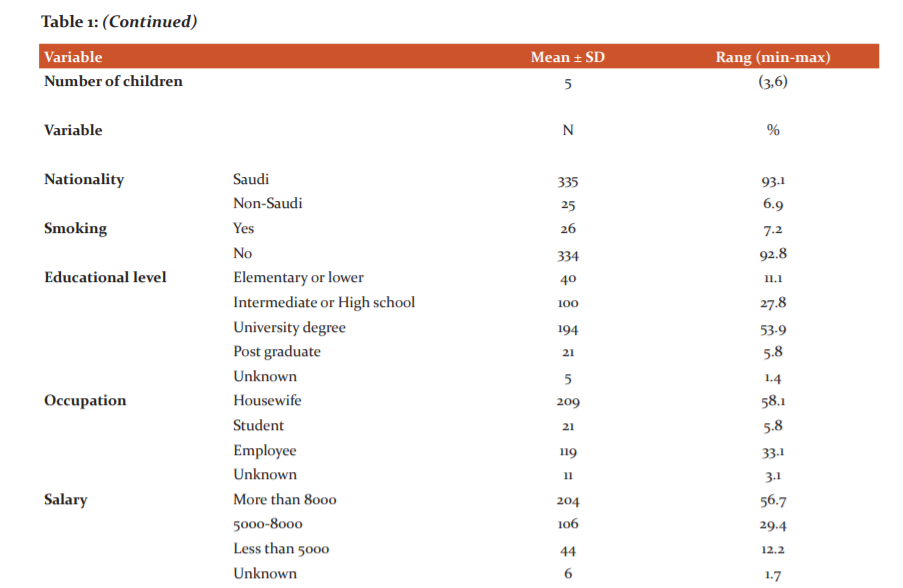

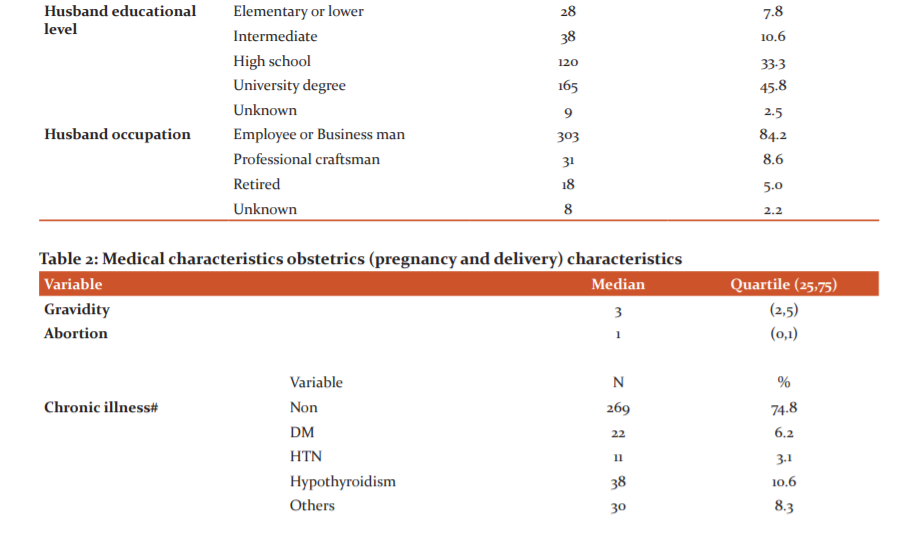

A total of 360 postpartum females who completed the demographic, obstetric variables section and the EPDS questionnaire were included in this study. The average age was 32.1 ± 7.2 years, 93.1% were Saudi. Only 26 (7.2%) were smokers. More than half 209 (58.1%) were housewives, 119 (33.1%) were students. More than half 194 (53.9%) had a university degree and 204 (56.7%)from group monthly income more than 8000 SR, 100 (27.8%) attend high school and 106 (29.4%) from group monthly income 5000-8000 SR. The majority of the participants reported that their husband was employed 303 (84.2%), with a university degree or higher (79.1%) (Table 1).

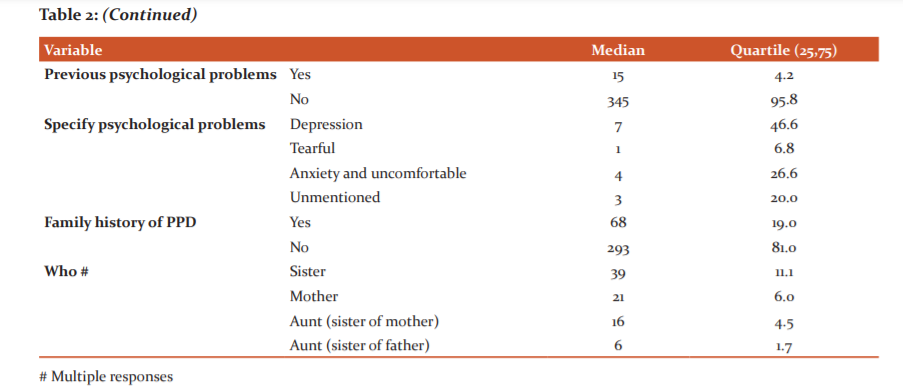

Out of the 360 postpartum females, 101 (28.2%) reported a medical problem, 15 (4.2%) reported Previous psychological problems and 68 (19%) reported a family history of PPD (Table 2).

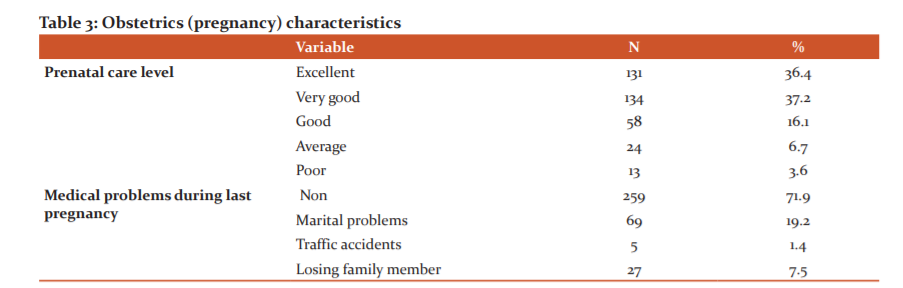

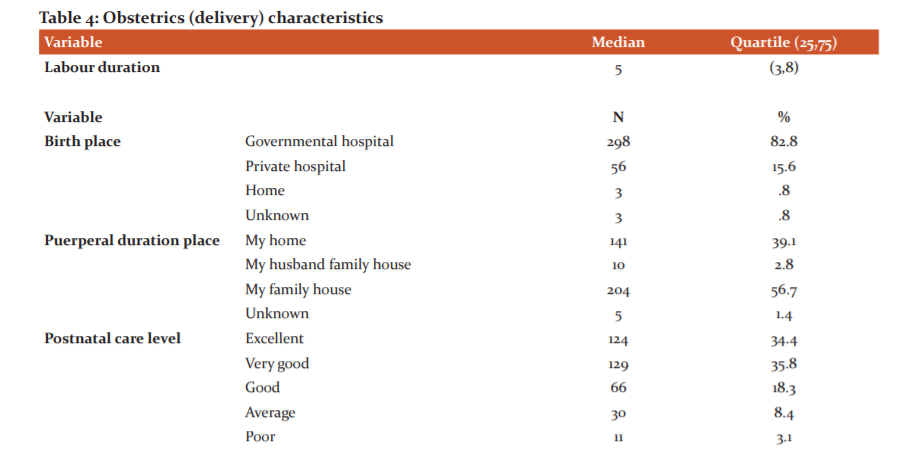

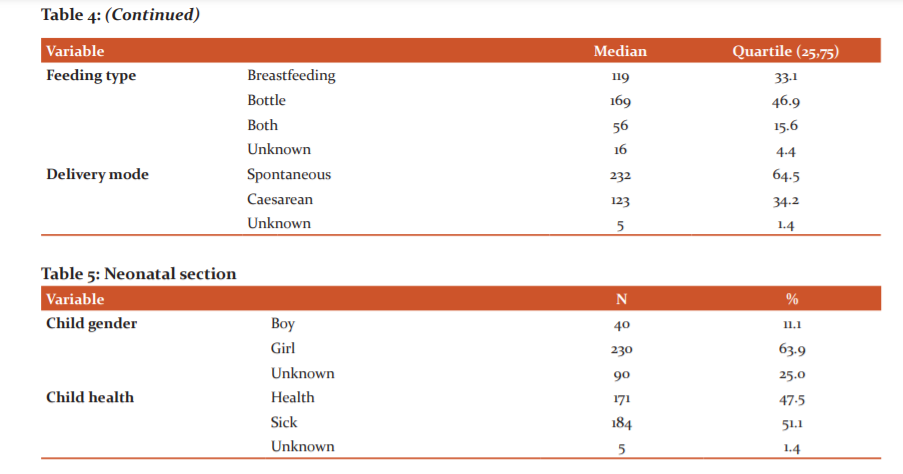

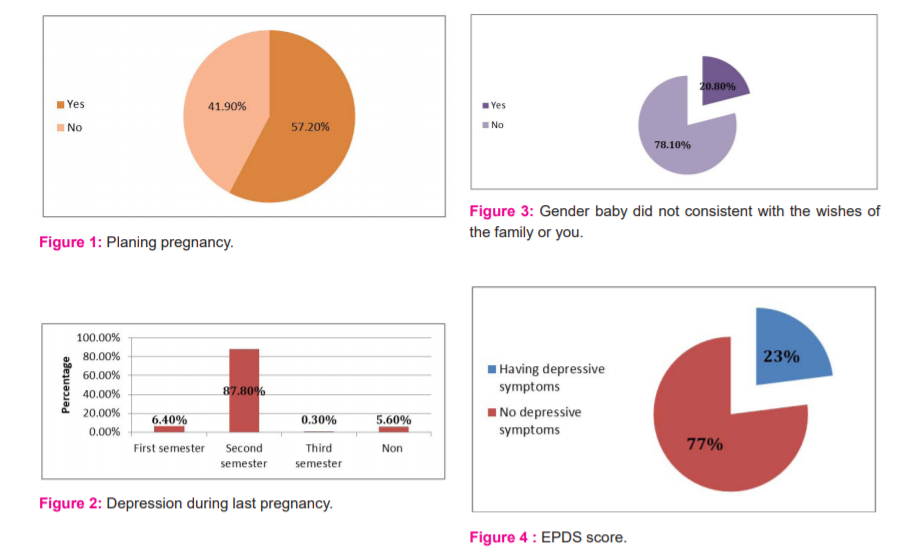

Out of the 360 postpartum females 206 (57.2%) planned for pregnancy, 101 (28.1%) reported medical problems during pregnancy, those who had Marital problems numbered 69(19.2%), those who suffered from depression during last pregnancy at least for one semester numbered 340 (94.4%). Out of the 360 postpartum females 298 (82.8%) delivered in governmental hospital and 56 (15.6%) delivered in a private hospital, those who spent Puerperal duration in her family house numbered 204 (56.7%), most of the female 232 (64.5%) delivered Spontaneously, 281 (78.1%) reported that baby gender they wish. More than two-third 265 (73.6%) and 253 (70.2%) reported (very good- excellent) prenatal and postnatal care respectively.

3.06/0boy, 184 (51.1%) baby reported a medical problem, and 169 (46.9%) reported bottle feeding (Tables 3-5 and Figures 1-3).

The EPDS mean score was 9.0±5.0 rang (0-30), and the median score was 7 with quartile (2,12). The score was divided into two categories with cut off > 13, out of the 360 mothers, 81 (23%) had depressive symptoms (EPDS score > 13), and 271 (77%) did not have depressive symptoms (EPDS scores ≤13) (Figure 4).

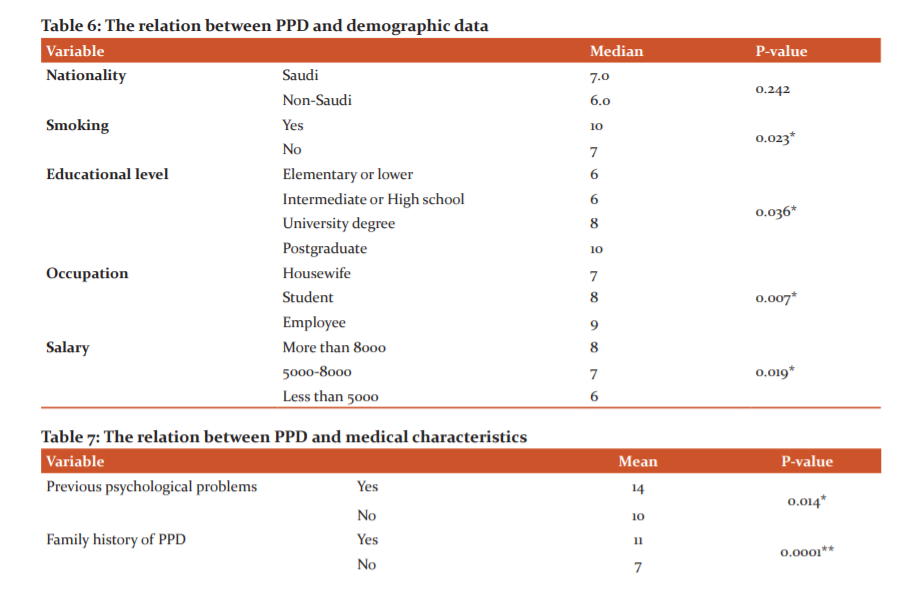

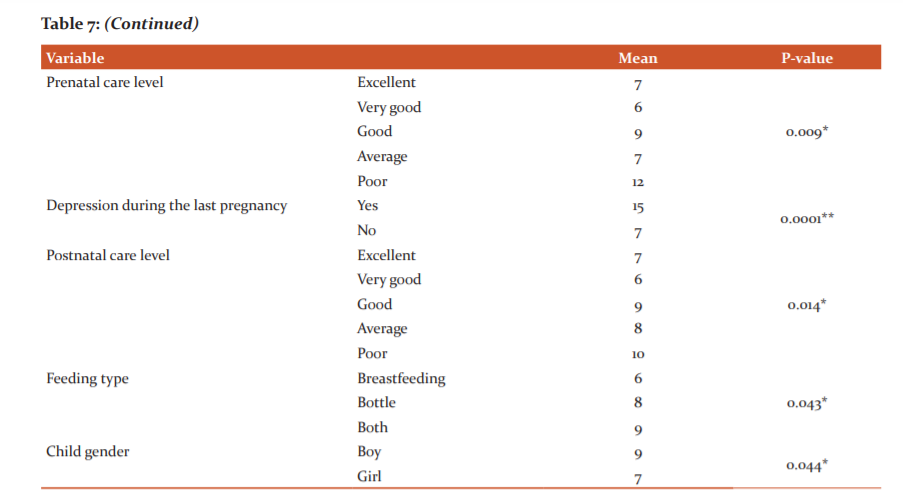

The results showed a significant association between PPD and the following sociodemographic and medical characteristics (maternal age, maternal education, maternal occupation, monthly income, being smoker, prenatal care, postnatal care, baby gender, semester depression, family history of PPD and previous psychological problems) were older age, lower level of education, working mother, lower monthly income, being smoker, depression during pregnancy, lower level of prenatal care, lower level of postnatal care, having boy, positive family history of PPD and previous psychological problems showed higher scores in EPDS (p=0.003, p=0.036, p=0.007, p=0.019, p=0.023, p<0.0001, p=0.009, p=0.014, p=0.044, p<0.0001and p=0.014) respectively (Tables 6 and 7).

DISCUSSION

Several studies were conduct about the prevalence of PPD and the associated risk factors, where PPD had big influence on the baby emotional and social development and this influence continue during teenage and adult years.20,21 In industrial countries there is rapid screening for PPD so an early intervention can be done to decrease the negative effects of PPD on mothers and babies lives.20,22

The present study aimed to investigate the prevalence and assess risk factors of post-partum depression symptom among post-partum mother in Al-Madinah, Saudi Arabia.

Results of this study showed that almost the fourth of participants mothers(23%) had depressive symptoms during post-partum period. This score was lower than previous studies in Saudi Arabia and Nepal which reported the prevalence of PPD 30-33% with cut off score ≥10,3,15,20 also the results from Pakistan studies showed that the prevalence was a range between 28%-63%,23 and in Indian studies the prevalence was between (15.0%-26.0).24

While the current prevalence was higher than other studies with the cut of ≥ 12 with the prevalence of 6%-12%,20,25,26 and when the cut off ≥ 13 the prevalence was 15.4% in the Turkey study.20

This Variety in the prevalence rate could be due to multi-cultural and multi-social factors, the difference cut off, sample size and methods. 3,20,26-29

The findings of the current study showed that mother aged more older mothers are more likely to develop PPD than younger mother (r=0.163, p value=0.03), similar results were found in Singapore, Saudi Arabia, Nepal and Canada studies the authors reported a high prevalence of PPD among women aged 35-40,2,29 in contrast in Turkey and Canada studies the authors reported high prevalence of PPD among young mother. 3,27,30,31

Several studies investigated the association between PPD occurrence and sociodemographic data (mother's education and occupation, monthly income and father's education and occupation),32-36 where the results showed contradictory evidence, in Nepal, Singapore, Turkey and Saudi study there was no association between mother's education level, occupation and low monthly income and PPD, 2,3,20,27 while in other studies there was a positive association between PPD and mother's lower education, being a housewife, and lower monthly income,3,20,27,37-42 also in 2007 study the authors reported a significant association between lower partner education and occupation and PPD.27,43 In contrast in 2017 Saudi Arabia study, the authors reported a significant association between PPD and mother low educational level, working mothers and high monthly income.15 In the current study showed consistent with the previous study regarding mother occupation and monthly income , where, working mothers and high monthly income had higher rate of PPD. Controversy the result showed that mother high educational level had the highest prevalence of PPD.

This differences in the percentage could be due to several factors such as socio-economic factors, sample size, and studies nature.

The current study findings showed that any medical problems in any time before or during pregnancy, during or after delivery had a strong effect on developing PPD (p=0.03p=0.004,p=0.03,p=0.01), this consistent with previous studies,2,3,20,32,44-46 In Saudi Arabia study the authors reported a significant association between anaemia during pregnancy and PPD,20 in Singapore study there was a significant association between medical problem during pregnancy such as Gestational diabetes mellitus GDM and hypertension and PPD.20,47,48

Besides, stressful life such as family problem, week relation with the husband or his family, previous psychological problems especially anxiety, exhausts, pregnancy depression, tearful and lack of sleep, and family history of PPD either first-degree relative or second-degree relative,2,3,15,20,32 In Nepal studies the authors reported that there is the relation between PPD and early contractions during pregnancy and maternity blues after seven days from delivery,3,49 in Turkey study the authors confirmed the relation between PPD and antepartum depressive symptoms which assessed by Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale- Depression HADS-D, and they reported that thinking in committing suicidal during pregnancy is a high-risk factor in developing PPD (odds ratio 6.99, CI 2.08– 23.49),27,50,51 similar results were found in Singapore study where the authors reported high prevalence of PPD among women with previous psychological problems.2,47,48 Inconsistent, the current study reported a significant relationship between the high score of EPDS and having previous psychological problems (p<0.0001), depression during last pregnancy (p=0.014) and having a family history of PPD (p<0.0001).

Regarding planning pregnancy and baby gender, the results of the current study showed no significant association between developing PPD and unplanned pregnancy. While there was a significant association between developing PPD and baby gender (p=0.04), this controversy with Turkey study.27

Several studies reported that breastfeeding decreases the risk of developing PPD. Where in the Riyadh study the score of EPDS was lower at 2 and 4 months (p < 0.0037 and p < 0.0001, respectively).52 Also in the Spain study, the authors reported that the long duration of exclusive breastfeeding the huge reduction of PPD incidence. 53This consistent with the result of the current study, where the lowest score was among mothers who breastfeeding 4 scores for breastfeeding 8 scores for bottle vs 9 scores for mixed feeding.

According to educational level, occupation and monthly income, this could be due to the facts that educational and employed women have more responsibilities and stressful life. Regarding age factor, previous pregnancies, place of delivery and previous pregnancy complications. This result could be because women who have several experiences and were pregnant had more responsibilities, previous experience with pain and pregnancy’ problem such as thick child, long labour, health problems.

CONCLUSION

Post-partum depression was reported among fourth of participant mothers. Both prenatal and postnatal care had a significant effect on developing PPD. Also, PPD was higher among boys’ mothers than girls’ mothers. Mothers with PPD were those older, higher educator, employed, high monthly income, those who previous psychological problems or depression, and those with a family history of PPD. We recommend that primary health care providers are requested to provide the necessary health education about PPD for all pregnant women through ANC. Encourage pregnant women to talk about PPD with their doctors. Mothers with a previous diagnosis of PPD or other psychological problems need more support from husbands and families. Further nation-wide studies on the assessment of PPD need to be conducted in larger sample size and regions other than AlMadinah Almunawarah, to identify the prevalence and associated risk factors.

Source(s) of support: Nil

Presentation at a meeting: Nil

Conflicting Interest (If present, give more details): Nil

References:

-

-

Bhusal BR, Bhandari N. Identifying the factors associated with depressive symptoms among postpartum mothers in Kathmandu, Nepal. Int J Nurs Sci 2018;5:268-274

-

Suhitharan T, Pham TP, Chen H, Assam PN, Sultana R, Han NL, et al. Investigating analgesic and psychological factors associated with risk of postpartum depression development: a case-control study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:1333-9.

-

Giri RK, Khatri RB, Mishra SR, Khanal V, Sharma VD, Gartoula RP. Prevalence and factors associated with depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers in Nepal. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:111.

-

Kalinin P, Arthur DG. Postpartum depression in Asian cultures: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46(10):1355–73.

-

Mehta S, Mehta N. An overview of risk factors associated with postpartum depression in Asia. Ment Illness 2014;6(1):5370.

-

Wisner KL, Chambers C, Sit DK. Postpartum depression: a major public health problem. JAMA 2006;296(21):2616–8.

-

Fisher J, Mello MCD, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(2):139–49.

-

Chaaya M, Campbell OMR, El Kak F, Shaar D, Harb H, Kaddour A. Postpartum depression: prevalence and determinants in Lebanon. Arch Women's Ment Health 2002;5(2):65–72.

-

DØRheim Ho†Yen S, Tschudi Bondevik G, Eberhard†Gran M, Bjorvatn BR. Factors associated with depressive symptoms among postnatal women in Nepal. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007;86(3):291–7.

-

Stewart DE, Robertson E, Dennis CL, Grace SL, Wallington T. Postpartum depression: a literature review of risk factors and interventions. https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/lit_review_postpartum_depression.pdf 2003.

-

Cox JL, Chapman G, Murray D, Jones P. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. J Affect Disord 1996;39(3):185-9.

-

Teissedre F, Chabrol H. A study of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) on 859 mothers: detection of mothers at risk for postpartum depression. Encephale 2004;30(4):376-81.

-

Alvardo-Esquivel C, Sifuentes-Alvarez A, Salas-Martinez C, Martinez-Garcia S. Validation of the Edinburgh postpartum depression scale in a population of puerperal women in Mexico. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2006;2(33).

-

Pitanupong J, Liabsuetrakul T, Vittayanont A. Validation of the Thai Edinburgh postnatal depression scale for screening postpartum depression. Psychiatry Res 2007;149(1e3): 253-9

-

Alamoudi DH, Almrstani AMS, Bukhari A, Alamoudi LH, Alsubaie AM, Alrasheed RK and Bajouh O. Prevalence and factors associated with depressive symptoms among post-partum mothers in jeddah. Int J Adv Res 2017;5(2):1542-1550.

-

TaW Northumberland. Postnatal Depression: a self-help guide. Northumberland: Tyne and Wear (NHS Trust); 2006:2003.

-

Patel VDN, Rodrigues M, DeSouza N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: a study of mothers in Goa. Indi., Am J Psychiatr 2002;159:43-47.

-

Khooharo YMT, Das C, Majeed N, Majeed N, Choudhry AM. Associated risk factors for postpartum depression presenting at a teaching hospital. ANNALS 2009;16(2):87-90

-

O'Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression metaanalysis. Int Rev Psychiatr 1996;8:37-54

-

Alharbi AA1, Abdulghani HM. Risk factors associated with postpartum depression in the Saudi population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014;10:311-6.

-

Markhus MW, Skotheim S, Graff IE, Frøyland L, Braarud HC, Stormark KM, et al. Low omega-3 index in pregnancy is a possible biological risk factor for postpartum depression. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67617.

-

Zauderer C. Postpartum depression: how childbirth educators can help break the silence. J Perinat Educ 2009;18(2):23–31.

-

Shah S. Frequency of postpartum depression and its association with breastfeeding: A cross-sectional survey at immunization clinics in Islamabad. J Pak Med Assoc 2017;67(8).

-

Prakash R, Ranadip RP, Chowdhury R, Salehi A, Sarkar K, Singh SK, et al. Postpartum depression in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95(10):706–717.

-

Nepal M, Sharma V, Koirala N, Khalid A, Shresta P. Validation of the Nepalese version of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in tertiary health care facilities in Nepal. Nep J Psychiatry 1999;1:46–50.

-

Regmi S, Sligl W, Carter D, Grut W, Seear M. A controlled study of postpartum depression among Nepalese women: validation of the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale in Kathmandu. Trop Med Int Health 2002;7(4):378–382.

-

Turkcapar AF1, Kad?o?lu N2, Aslan E3, Tunc S4, Zay?fo?lu M, Mollamahmuto?lu L. Sociodemographic and clinical features of postpartum depression among Turkish women: a prospective study. BMC Pregn Childbirth. 2015;15:108.

-

DØRheimHo†Yen S, TschudiBondevik G, Eberhard†Gran M, Bjorvatn BR. Factors associated with depressive symptoms among postnatal women in Nepal. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007;86(3):291–297.

-

Muraca GM, Joseph KS. The association between maternal age and depression. J Obstet Gynecol Can 2014;36(9):803–810.

-

Daoud N, Shoham-Vardi I, Urquia ML, O’Campo P. Polygamy and poor mental health among Arab Bedouin women: do socioeconomic position and social support matter? Ethn Health 2014;19(4):385-405.

-

Shepard LD. The impact of polygamy on women’s mental health: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2013;(1):47–62.

-

Vigod S, Villegas L, Dennis C-L, Ross L. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: a systematic review. BJOG 2010;117:540–550.

-

Ege E, Timur S, Zincir H, Geckil E, Sunar-Reeder B. Social support and symptoms of postpartum depression among new mothers in Eastern Turkey. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2008;34(4):585-593.

-

Kheirabadi GR, Maracy MR, Barekatain M, Salehi M, Sadri GH, Kelishadi M, et al. Risk factors of postpartum depression in rural areas of Isfahan Province, Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12(5):461-467.

-

Savarimuthu RJ, Ezhilarasu P, Charles H, Antonisamy B, Kurian S, Jacob KS. Post-partum depression in the community: a qualitative study from rural South India. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2010 56(1):94-102.

-

Stewart RC, Bunn J, Vokhiwa M, Umar E, Kauye F, Fitzgerald M, et al. Common mental disorder and associated factors amongst women with young infants in rural Malawi. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2009;45(5):551-559.

-

Clarke K, Saville N, Shrestha B, Costello A, King M, Manandhar D, et al. Predictors of psychological distress among postnatal mothers in rural Nepal: a cross-sectional community-based study. J Affect Disord 2014;156:76–86.

-

O’hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression-a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996;8(1):37–54.

-

Lee DT, Yip AS, Leung TY, Chung TK. Identifying women at risk of postnatal depression: prospective longitudinal study. Hong Kong Med J 2000;6(4):349–354.

-

Goker A, Yanikkerem E, Demet MM, Dikayak S, Yildirim Y, Koyuncu FM. Postpartum depression: is mode of delivery a risk factor? ISRN Obstet Gynecol 2012;2012:616759.

-

Saleh El-S, El-Bahei W, El-Hadidy MA, Zayed A. Predictors of postpartum depression in a sample of Egyptian women. Neuro Psychiatr Dis Treat 2013;9:15–24.

-

Segre LS, O’Hara MW, Arndt S, Stuart S. The prevalence of postpartum depression: the relative significance of three social status indices. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007;42:316–321.

-

Da-Silva VA, Moraes-Santos AR, Carvalho MS, Martins MLP, Teixeira NA. Prenatal and postnatal depression among low income Brazilian women. Braz J Med Biol Res 1998;31:799-804.

-

Ross LE, Dennis CL. The prevalence of postpartum depression among women with substance use, an abuse history, or chronic illness: a systematic review. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18(4):475-486.

-

Chaaya M, Campbell OM, El Kak F, Shaar D, Harb H, Kaddour A. Postpartum depression: Prevalence and determinants in Lebanon. Arch Womens Ment Health 2002;5:65–72.

-

Fo¨ rger F, Ostensen M, Schumacher A, Villiger PM. Impact of pregnancy on health-related quality of life evaluated prospectively in pregnant women with rheumatic diseases by the SF-36 health survey. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1494–1499.

-

Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;26(4):289–295.

-

Chee CY, Chong YS, Ng TP, Lee DT, Tan LK, Fones CS. The association between maternal depression and frequent non-routine visits to the infant’s doctor – a cohort study. J Affect Disord 2008;107(1–3):247–253.

-

Gonidakis F, Rabavilas AD, Varsou E, Kreatsas G, Christodoulou GN. A 6-month study of postpartum depression and related factors in Athens Greece. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(3):275–82.

-

O’Hara MW. Postpartum depression: what we know. J Clin Psychol 2009;65:1258–1269.

-

Orsel S, Karadag H, Turkcapar H, Kahilogullari AK. Diagnosis and classification subtyping of depressive disorders: comparison of three methods. Bull Clin Psychopharmacol 2010;20:57–65.

-

Hamdan A1, Tamim H. The relationship between postpartum depression and breastfeeding. Int J Psychiatry Med 2012;43(3):243-259.

-

Cristina Borra,corresponding author Maria Iacovou, and Almudena Sevilla. New Evidence on Breastfeeding and Postpartum Depression: The Importance of Understanding Women’s Intentions. Matern Child Health J 2015;19(4):897–907.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License