IJCRR - 3(9), September, 2011

Pages: 149-158

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

EFFECT OF CARDIAC REHABILITATION ON MYOCARDIAL CONTRACTILITY IN CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE PATIENTS: A TRIAL FROM IRAN

Author: Mohammad H Haddadzadeh, Arun G Maiya, Bjan Shad, Fardin Mirbolouk, R Padmakumar , Vasudeva Guddattu

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Objective: However Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) is the leading cause of death worldwide, there is a scarcity of data on effectiveness of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programs on myocardial

contractility as predictor of long term prognosis and so the present study aimed to investigate the same in

post coronary event patients.

Methods: In a Single blinded, Randomized controlled trial, Post-Coronary event CAD patients with age group of 35 to 75 years, surgically (CABG or PTCA) or conservatively treated were recruited from

Golsar Hospital; Iran. Exclusion criteria were high risk group (AACVPR-99) patients and any

contraindication to exercise testing and training. Recruited patients were randomized either into Hospitalbased,

Home-based cardiac rehabilitation or Control by means of block randomization (block size of 6)

and concealed envelope method. Patients in the study group [Hospital (HsCR) and Home-based(HmCR)]

underwent 12 weeks individually tailored exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation according to the ACSM-

2005 guidelines. Control group only received the usual cardiac care without any exercise training.

Myocardial contractility in terms of LVEF was measured by echocardiography before and after 12 weeks

of exercise training in both groups as well as control. Differences between and within groups were

analyzed using one way ANOVA keeping level of significance at 0.05.

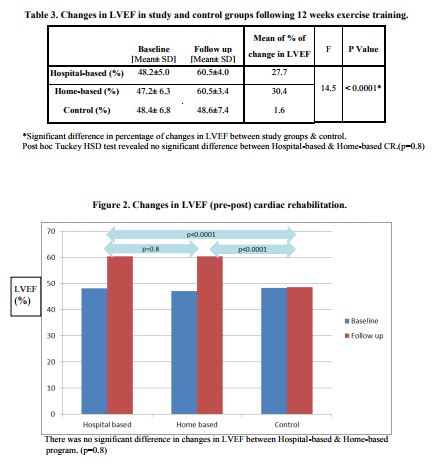

Results: 42 patients having given written, informed consent with mean age of 59.8\? 9.0 enrolled. There was a significant increase in LVEF in both study groups (48.2\?5.0 to 60.5\?4.0 in HsCR and 47.2\? 6.3 to

60.5\?3.4 in HmCR) group compare to control (48.4\? 6.8 to 48.6\?7.4) group (p< 0.0001).

Conclusion: 12 weeks early (within one month post-discharge) structured individually tailored cardiac

rehabilitation significantly improved LVEF in post coronary event patients.

Keywords: Exercise training, Cardiac Rehabilitation, Myocardial Contractility, Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Middle Eastern countries such as Iran are joining the global obesity pandemic and its consequences such as CAD. [1] Coronary Artery disease (CAD) is one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in different communities worldwide [2,3,4]. Despite the lack of accurate data, there is some evidence to indicate that CAD is increasing in magnitude in Iran[2] and accounts about 50% of all deaths per year.[5] While age-adjusted mortality from CAD is gradually falling in developed countries, [3,6] the rate has increased by 20%–45% in Iran.[7,8] Myocardial contractility in terms of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) is an clinical index of pumping action of heart,[9,10] and is a well-established predictor of mortality and long term prognosis in acute myocardial infarction.[10,11] However exercise training is the core component of cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of CAD, there is less body of evidence on effectiveness of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on LVEF in CAD patients. Previous published studies mainly studied this outcome in heart failure patients or they used a heterogeneous groups of patients with respect to the time gap between coronary event and start of exercise training or total duration of the program. The purpose of this study was to find out the effect of early (within one month post discharge) structured individually tailored exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on (LVEF) in post- Coronary event patients. As to our knowledge, this study was the first of such trial in the country.

METHODS

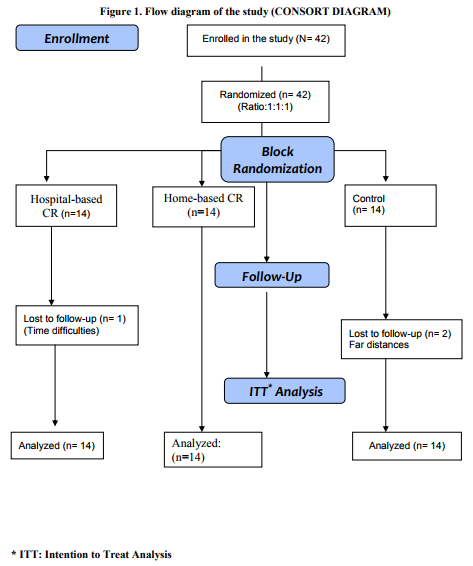

Study Design. Study procedure was designed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration new revision 2000. Ethical committee of Golsar Hospital approved the study. This was a single blinded randomized controlled trial in which the effectiveness of early structured individually tailored exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on myocardial contractility was studied. Eligible patients who given a written informed consent were allocated into study or control groups by means of block randomization (block size of 6) using concealed envelope method. The assessor of main outcome who was a cardiologist was unaware of allocation of patients. (Figure1)

Subjects. Post-coronary event patients whom were treated surgically (CABG or PTCA) or conservatively were recruited between July to November 2009 at Golsar Hospital, Rasht; Iran. Golsar Hospital is a general hospital and offers outpatient Cardiac Rehabilitation program under department of Physiotherapy.

Inclusion criteria. Patients of both sexes were screened for eligibility criteria including age group of 35 to 75 years who were post-event (within one month post discharge) coronary artery disease patients treated either surgically (CABG or PTCA) or conservatively.

Exclusion criteria. High risk group patients (AACVPR-99)[12] or any systemic, orthopedic or neurological conditions which restrict participating in aerobic exercise and patients who were contraindicated for exercise testing and training were excluded from the study.

Procedure. After approval from Ethical Committee of Hospital, all eligible patients were explained about the procedure and written informed consent was obtained from them before allocating them into different groups. Eligible and consenting patients were randomized into Hospital-based Cardiac Rehabilitation, Home-based cardiac rehabilitation or Control group by means of block randomization (block size of 6) and concealed envelope method. Base line data included the Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) measured by echocardiography, and demographic and clinical evaluation was taken. Patients in study groups underwent a 12 weeks structured individually tailored exercise training either in the form of Hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation (HsCR) or Home-based program (HmCR). After 12 weeks of exercise training subjects were reassessed clinically for the primary outcome and results were compared pre and post-intervention with control group. All patients underwent a Graded exercise test (GXT) with Bruce protocol at base line in order to risk stratify the patients (AACVPR-99) and the results of the test included MET and achieved HRPeak were used as baseline for exercise prescription according to Karvonen formula.

Exercise Training Group Authors used ACSM-2005[13] guidelines as principle for exercise prescription for study groups. The intensity of prescribed exercise calculated based on Heart Rate Reserve achieved during graded exercise test (Bruce protocol) as well as Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE). Target Heart Rate Range (THRR) using Karvonen formula was applied to prescribe exercise intensity. All recruited subjects were given orientation to the program. A session of informal health education about their condition was given by the physiotherapist to the patients and to their family members. Risk factors modifications advice according to the risk factors of each patient, life style modification, and smoking cessation advice were given prior to the start of rehabilitation program. Awareness about cardiac rehabilitation, exercise program, adherence to the program and its benefits which they attend explained to the study group to increase the rate of the attendance and compliance.

Group IA. Hospital-Based Group This group underwent a structured, supervised exercise training program for a period of 12 weeks. They attended a minimum of three days exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in the hospital set up. The exercise program consisted of 5-10 minutes warm up (Breathing exercise, stretching exercise and walking on treadmill) followed by graded aerobic training and 5- 10 minutes cool down. Graded aerobic training was mainly treadmill walk 3-5 times per week, with Intensity of 40-70 % of HRR achieved in exercise test applying Karvonen formula, and RPE of 11 to 14 for a duration of 20 to 40 minutes. (ACSM guidelines)[13]

Group IB. Home-based Group

Exercise component of cardiac rehabilitation program for home-based group was an individualized tailored program of aerobic exercises; preferably brisk walking as it is shown in the literature that brisk walking provide an activity intense enough to increase aerobic capacity in healthy sedentary as well as cardiac patients.[14] Initial session of exercise prescription and training were given in the department under physiotherapist supervision, and then the program protocol was given to the patient to do at home for 12 weeks. Intensity of exercise converted to a safe range of speed of walk which patient achieved on treadmill to use as a base for brisk walking. Patients were also trained in palpating the pulse and calculating the heart rate, and to rate the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) of 11 to 14. The exercise program consisted of 5-10 minutes warm up including Breathing exercise, stretching exercise and gentle active exercise to larger muscle groups like lower limb and trunk muscles followed by graded aerobic training and cool down. Graded aerobic training was mainly brisk walking for 3-5 times per week with intensity of 40-70 % of HRR achieved in exercise test applying Karvonen formula, converted to speed of walk, and RPE of 11-14 for duration of 20 to 40 minutes. (According to ACSM guidelines)[13] Patients in HCR group were regularly contacted by phone every two weeks to find out their adherence to the program and advice or changes in program if necessary and to monitor the progress. The exercise log was reviewed every 15 days. Subjects also were advised to contact the physiotherapist if any advice or help needed. Trained physiotherapist gave them detailed awareness of signs and symptoms to be monitored while doing exercise program, do and don‘t and the criteria for the termination of exercise were well explained to them.

Exercise intensity progression As the conditioning effect of exercise training, progression of the exercise intensity was done as needed. As the RPE falls with improving fitness the intensity of exercise was increased at 5 to 10 percent of the maximum heart rate and by maintaining RPE of 11 to 14 throughout the 12 weeks of duration. For the first four weeks patients did exercise training for 15 to 20 min., from 5th to 8th week increased to 20 to 30 minutes, and the final 9th to 12th week duration was increased to 30 to 40 minutes.

Monitoring

Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE): RPE provides a subjective means of monitoring exercise intensity. HR-VO2 relationship could be evaluated further in relation to individuals RPE which is helpful in monitoring the exercise intensity. This method is appropriate for setting exercise intensity in persons with low fitness, cardiac patients and those who are under medication that affect HR response to exercise; taking into account personal fitness level, environmental conditions and general fatigue level.[14] Light to moderate intensity (RPE of 11 to 14) is suitable for cardiac patients. It is important to use standardized instruction to reduce problems of misinterpretation of RPE. The following instruction is recommended by ACSM guidelines:[13] ?During the exercise we want you to pay close attention to how hard you feel the exercise work rate is. This feeling should reflect your total amount of exertion and fatigue, combining all sensations and feeling of physical stress, effort and fatigue. Do not concern yourself with any one factor such as leg pain, shortness of breath or exercise intensity, but try to concern on your total inner feeling of exertion. Try not to underestimate or overestimate your feeling of exertion. Be as accurate as you can.? Other symptomatic complaints such as degree of chest pain, angina, burning sensation discomfort, and dyspnea collected from the patients routinely.[13]

Indications for termination of exercise: Detailed awareness of signs and symptoms to be monitored while doing exercise program and subjective symptoms and criteria for the termination of exercise were well explained to the subjects.

Group II: Control Group In the control group, subjects underwent baseline assessment, and these patients were instructed to follow medical treatment advised by their physician and only education program were given to them. They were not advised any extra formal exercise training program.

RE-ASSESSMENT After 12 weeks, post-intervention re-evaluation was done by echocardiography in both; study as well as control group.

DATA ANALYSIS Sample size was determined by using a pilot study of 10 patients. Within group improvement of 5 % in LVEF was considered as clinically significant. At alpha= 0.05 and power of 90% authors determined a sample size of 42 subjects. Analyses were performed by using intention to treat approach. Statistical software SPSS v17 was used to infer the data. One way ANOVA was used to compare mean of changes between groups.

RESULTS A total of 42 (33 Male, 9 Female) subjects with mean age of 59.8± 9.0 years enrolled in the study. In Hospital-based group one patient discontinue the program because of Time and Scheduling difficulties. And in control group 2 patients lost to follow up due to far distances. Summary flowchart of study according to CONSORT guidelines is shown in Figure 1.

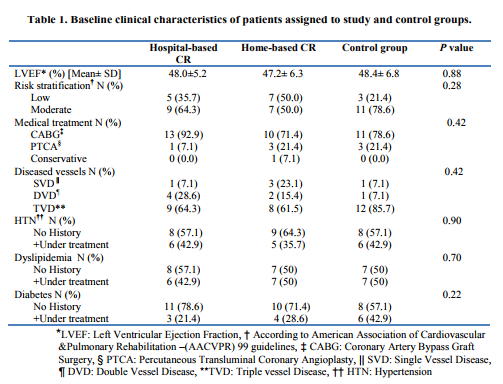

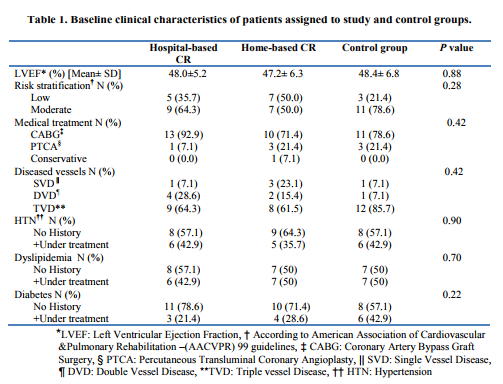

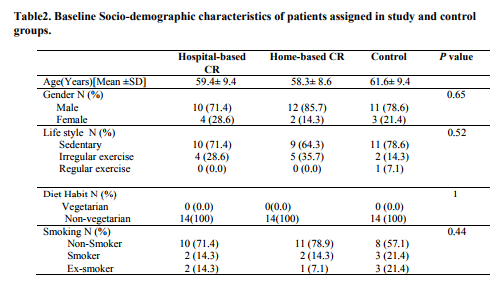

Rest of subjects in study groups completed their course of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation with a minimum of 70% attendance in the exercise sessions. Both study groups and control group had similar demographic and clinical characteristics at base line with respect to the LVEF, risk stratification, number of diseased vessels, life style, educational level, and diet habits and age. (Tables 1and 2) Base line LVEF was 48.2±5.0 in Hospital-based group, 47.2± 6.3 in Home-based group and 48.4± 6.8 in Control group. There was a significant improvement in LVEF after 12 weeks of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in both study groups compared to control. (Table 3) Post hoc Tucky HSD revealed no significant difference in changes in LVEF between Hospital-based and Home-based cardiac rehabilitation. (Figure 2)

DISCUSSION

However decreased left ventricular systolic function is a well-established independent predictor of mortality in coronary artery disease patients, few data are available regarding the effect of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on LVEF.[11] The existing literature either focus more on heart failure patients or they have lack of methodological uniformity regarding the type of patients, time gap between post-discharge to start of exercise training in post-event patients or the intensity and type of exercise given to the patients. Koch, Duard and Broustet (1992) in a randomized clinical trial studied the effect of graded physical exercise on EF and they found no significant effect. But their study was conducted on chronic heart failure patients. [15] Adachi, Koiket, Obayshi (1996) reported improvement in cardiac function (such as stroke volume), both at rest and during exercise only with high intensity exercise training. [16] The present study demonstrated two important findings. First, an early (within one month postdischarge) 12 weeks structured exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in post-event coronary artery disease patients significantly improved the myocardial contractility in terms of LVEF. Second, a structured individually tailored Homebased exercise training could be as effective as Hospita;-based programs and safely used not only in low risk but also in moderate risk (AACVPR-99) coronary artery disease patients. These programs could be started as early as 2 weeks post discharge in uncomplicated patients. These findings are in consistent with results from Haddadzadeh, Maiya et al. in their recent study in India who found a similar effect in a RCT.[17] Giallauria et al., also found a favorable remodeling from six months exercise training program in patients with moderate left ventricular dysfunction.[18] Since evidence shows there are many difficulties and barriers to long term Center based exercise training and only 25 % to 30 % of eligible patients attend exercise based Cardiac rehabilitation programs, individually tailored home based exercise training programs could be an alternative method in improving myocardial contractility without affecting the efficacy of programs.

Limitation One of the limitations of present study was in order to randomize the patients in Hospitalbased-based group authors had reimbursed the expenses of Cardiac Rehabilitation program to convince those patients who randomized to Hospital-based group and were not willing to continue because of its expenses or far distances to continue the program. As to our knowledge, this was the first RCT in Iran to investigate the effectiveness of structured exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on LVEF. Applying the finding into practice, amplifies the importance of secondary prevention and effectiveness of early exercise based cardiac rehabilitation programs on overall and cardiac condition of patients. Keeping in mind the increasing number of cardiovascular disease in Middle East countries including Iran, forwarding the message to the policy makers, insurance companies for covering the cardiac rehabilitation expenses, hospital administrative for necessity of such programs and adjusting the need of the common people with the available resources in the form of Home-based programs without losing the efficacy is must.

CONCLUSIONS Authors concluded that 12 weeks structured Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programs significantly improved myocardial contractility in terms of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in post coronary-event patients. Authors also concluded that an individually tailored structured Home-based cardiac rehabilitation was as effective as Hospital-based program in improving LVEF. Thus, Home-based cardiac rehabilitation program if individually tailored for each patient is an effective alternative to Hospital-based programs to improve myocardial contractility.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Authors would like to thank the primary funding agency; Armaghan Educational Institute, through Ministry of Education of Iran, as a part of larger multicenter study, Prof Sreekumaran Nair; Head of Dep. of Biostatistics; Manipal University for his suggestion and support, Dep. of Physiotherapy, Angioplasty and Exercise Test Unit of Golsar Hospital for their complete support.

Conflict of Interest Authors agree that there was no source of conflict of interest.

References:

1. Bahrami H, SadatSafavi M, Pourshams A, et al. Obesity and hypertension in an Iranian cohort study; Iranian women experience higher rates of obesity and hypertension. Public Health. 2006; 6:158-166.

2. Hadaegh F, Harati H, Ghanbarian A , Azizi F. Prevalence of coronary heart disease among Tehran adults: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2009.

3. Castelli WP. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease: the Framingham study. American journal of medicine, 1984, 76(2A):4–12.2.

4. Keil U. Das weltweite WHO-MONICAProjekt: Ergebnisse und Ausblic [The worldwide WHO MONICA Project: results and perspectives]. Gesundheitswesen, 2005, 67(Suppl. 1):S38–45.

5. ZN Hatmi, S Tahvildari, A Gafarzadeh Motlag and A Sabouri Kashani. Prevalence of coronary artery disease risk factors in Iran: a population based survey. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2007, 7:32.

6. Sytkowski PA et al. Sex and time trends in cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality: the Framingham heart study. American journal of epidemiology, 1996, 143(4):338–50.

7. Prevention and control of cardiovascular disease. Alexandria, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 1995:24.

8. Zali M, Kazem M, Masjedi MR. [Health and disease in Iran]. Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran, Deputy of Research, Ministry of Health, 1993 (Bulletin No. 10) [in Farsi].

9. Andria M, et.al. Attendance and graduation patterns in a group model health maintenance organization. Alternative cardiac rehabilitation program. J Cardiopul Rehab. 2004; 24: 15-156. International Journal of Current Research and Review www.ijcrr.com Vol. 03 issue 09 September 2011 155

10. Johnson N, et al. Factors associated with referral to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation services. J Cardiopul Rehab. 2004;24: 165- 170.

11. Dutcher JR, Kahn J, Grines C, Franklin B. Comparison of left ventricular ejection fraction and exercise capacity as predictors of two and five-year mortality following acute myocardial infarction. Am j Cardiol. 2007; 99:436-441.

12. American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Guidelines for Cardiac Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention Program. 3rd ed. Champaign, IL; Human kinetics, 1999.

13. American College Of Sports Medicine (ACSM) – Guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 7th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkines. 2006.

14. Machionni N, Fattirolli F, Fumagalli S, et al. Improved exercise tolerance and quality of life with cardiac rehabilitation of older patients after myocardial infarction: results of a randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2003; 107:2201-2206.

15. Koch M, Douard H, Broustet JP. The benefit of graded physical exercise in chronic heart failure. Chest. 1992;101 : 231-5.

16. Adachi H, Koike A, Obayashi T, et al. Does appropriate endurance exercise training improve cardiac function in patients with prior myocardial infarction? Europ Heart J. 1996; 17: 1511-21.

17. Haddadzadeh M H, Maiya A G, Padmakumar R, Devasia T, Kansal N, Borkar S. Effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation on myocardial contractility in post-event coronary artery disease patients: A randomized controlled trial. Physiotherapy.2010; 8(2):5-12.

18. Giallauria F, Cirillo P, Lucci R, Pacileo M, De Lorenzo A, D'Agostino M, et al. Left ventricular remodelling in patients with moderate systolic dysfunction after myocardial infarction: favourable effects of exercise training and predictive role of Nterminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008 Feb;15(1):113-8.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License