IJCRR - 6(1), January, 2014

Pages: 28-33

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

ASSESSMENT OF METAL CONTENT IN LEAFY VEGETABLES SOLD IN MARKETS OF LIBREVILLE, GABON

Author: Roger Ondo Ndong, Armelle Lyvane Ntsame Affane, Hugues Martial Omanda, Philippe Padoue Nziengui, Richard Menye Biyogo, Jean Aubin Ondo, Aime-Jhustelin Abogo Mebale

Category: Healthcare

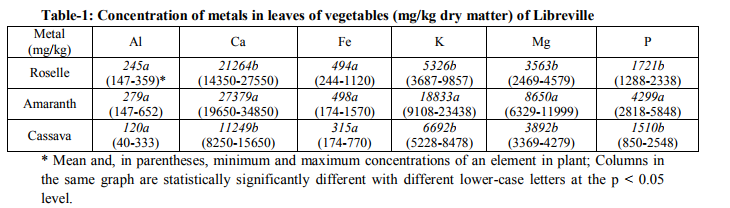

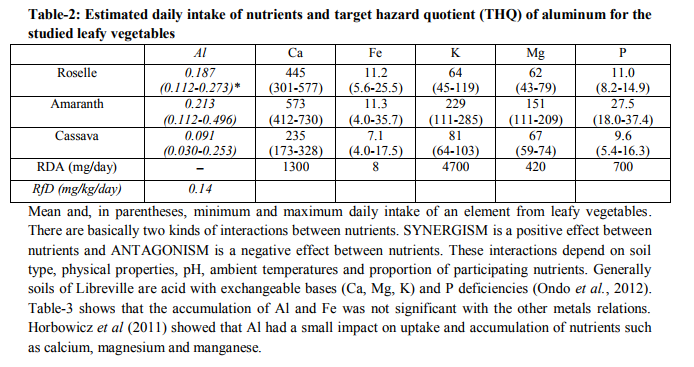

Abstract:The rate of urbanization in developing countries imposes to develop standards for efficient food security. This study was conducted in 2013 in Libreville, Gabon to evaluate the metal concentration in three leafy vegetables commonly consumed in West Africa. Amaranthus cruentus (Amaranth), Hibiscus sabdariffa (Roselle) and Manihot esculentus (Cassava) were sampled in seven markets of Libreville (Gabon) and analyzed for their concentration in Al, Ca, Fe, K, Mg and P using ICP-AES. The concentration ranges found were 11-173 mg/kg, 5897-24911 mg/kg, 135-1220 mg/kg, 1531-9728 mg/kg, 1470-7146 mg/kg and 186-1277 mg/kg for Al, Ca, Fe, K, Mg and P, respectively. These results indicated that amongst the leafy vegetables studied, Amaranthus cruentus was the best source of nutrients (Ca, Fe, K, Mg and P). However concerns could be raised for the some high aluminum content found in these leafy vegetables which may be detrimental to human and animal health.

Keywords: leafy vegetables, nutrients, aluminum, daily intake, target hazard quotient.

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Population growth forecasts for year 2030 indicate that the world population will increase and reach 9 billion inhabitants. This growth will particularly occur in the urban areas of developing countries, creating a situation of exploding alimentary needs. In response to this considerable challenge, urban agriculture, which was almost insignificant thirty years ago, has developed in cities and has reached a phase of rapid expansion in developing countries. Therefore, it is important to assess the nutritional quality of cultivated vegetables (Ondo et al., 2013). The consumption of vegetable and fruits has increased through urban agriculture, which provides fresh produces throughout the year (Kawashima and Soares, 2003). This has led to improve and balance people’s diets since fresh produces represent important source of proteins, vitamins and minerals for humans (Akbar et al., 2010). Indeed, humans require more than 22 mineral elements, all of which can be supplied by an appropriate diet. Each mineral has a particular function within the body. For example, calcium (Ca) functions as a constituent of bones and teeth, regulation of nerve and muscle function. Calcium absorption requires calcium-binding proteins and is regulated by vitamin D, sunlight, parathyroid hormone and thyrocalcitonin. Growing, pregnant and especially lactating humans and animals require liberal amounts of calcium (Soetan et al., 2010). Phosphorus (P) is located in every cell of the body. It functions as a constituent of bones, teeth, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), phosphorylated metabolic intermediates and nucleic acids. Practically, every form of energy exchange inside living cells involve the forming or breaking of high-energy bonds that link oxides of phosphorus to carbon or to carbon-nitrogen compounds (Soetan et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2000). Potassium (K) is the principal cation in intracellular fluid and functions in acid-base balance, regulation of osmotic pressure, conduction of nerve impulse, muscle contraction particularly the cardiac muscle, cell membrane function and Na+/K+-ATPase. Plant products contain many times as much potassium as sodium. Sources include vegetables, fruits, nuts (Soetan et al., 2010). Magnesium (Mg) is an active component of several enzyme systems in which thymine pyrophosphate is a cofactor. Approximately one-third to one-half of dietary magnesium is absorbed into the body (Murray et al., 2000). Iron (Fe) functions as haemoglobin in the transport of oxygen. In cellular respiration, it functions as essential component of enzymes involved in biological oxidation. Brain is quite sensitive to dietary iron depletion and uses a host of mechanisms to regulate iron flux homostatically (Batra and Seth, 2002). For example, excessive accumulation of iron in human tissues causes haemosiderosis (Akpabio et al., 2012; Murray et al., 2000). Sources of iron include red meat, spleen, heart, liver, kidney, fish, egg yolk, nuts, legumes, molasses, iron cooking ware, dark green leafy vegetables. Aluminum (Al) is the third most abundant element in the earth’s crust. Increased aluminum exposure has the potential to cause a number of health problems such as anemia and other blood disorders, colic, fatigue, dental caries, dementia dialactica, kidney and liver dysfunctions, neuromuscular disorders, osteomalacia and Parkinson’s disease (Lokeshappa et al., 2012). Thus, due to the multiple roles of metals and their importance in human’s diet, the main objective of the present work is to evaluate the metal and nutrient composition of commonly consumed leafy vegetables sold in marketplaces of Libreville.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of samples, sample preparation and treatment:

This study was conducted in Libreville, capital of Gabon (9°25’ east longitude and 0°27’ north latitude). The climate is equatorial type. The annual rainfall varies from 1,600 to 1,800 mm. Average temperatures oscillate between 25 and 28°C with minima (18°C) in July and maxima (35°C) in April. Three types of leafy vegetables were randomly purchased in seven markets of Libreville, which were the markets of Okala, Nkembo, Owendo, PK8, Akébé, NzengAyong and Mont-Bouet. The leafy vegetables bought were amaranth (Amaranthus cruentus), roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) and cassava (Manihot esculenta). The vegetables were brought to the laboratory where they were washed with distilled water to remove dust particles. Then, after separating the leaves from the other parts of plants with a knife. these latter were air-dried, then oven-dried at 70?C. Dried leaves samples were ground into a fine powder using a mill of IKA A10 type, thereafter stored in polyethylene bags kept at room temperature. 500 mg of plant samples were digested at 150°C for 1 hour in a microwave mineralizer, using a mixture of nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide and ultra-pure water with a volume proportion ratio of 2:1:1 (Nardi et al., 2009). Each mineralization product was filtered through a 0.45-μM filter (PTFE, from Millipore, Massachusetts, USA) and the metal concentrations determined by the ICPAES method (Activa M model, JobinYvon, France). Daily intake of metals (DIM): The estimated daily intake (DIM) of Al, Ca, Mg, Fe, K and P through vegetable consumption was calculated as: DIM=[M]×K×I where [M] is the heavy metal concentration in the plant (mg/kg), K is the conversion factor used to convert fresh part consumed plant weight to dry weight, estimated as 0.085, and I is the daily intake of consumed plant, estimated as 0.255 kg/day per adult. Target hazard quotient (THQ): The health risks to local inhabitants from consumption of vegetables were assessed based on the THQ, which is the ratio of a determined dose of a pollutant to a reference dose level. As a rule, the greater the value of the THQ is above unity, the greater the level of concern is high. The method of estimating risk using the THQ is based on the equation THQ = [(EFr × ED × FI × MC) / (RfD × BW × AT)] × 0.001 where EFr is exposure frequency (365 days/year), ED is exposure duration (60 years for adults), FI is food ingestion, MC is the metal concentration in the food (mg/kg fresh weight), RfD is the oral reference dose (mg/kg/day), BW is the average body weight for an adult (60 kg) and AT is the average exposure time for non carcinogenic effects (365 days/year ×number of exposure years, assuming 60 years in this study). The RfD is an estimation of the daily exposure for people that is unlikely to pose an appreciable risk of adverse health effects during a lifetime and was based on value of 0.14 mg/kg/day for Al. Statistical analysis: The significance of differences between the means of metals in leaves, the edible part of plants, was evaluated by Tukey’s test (P<0.05). Statistical analyses were performed with the software XLSTAT, Version 2010 (Addinsoft, Paris, France).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

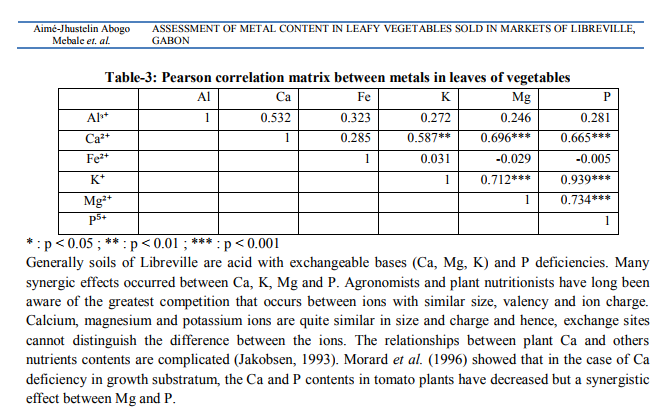

The accumulation of metals in vegetables depends on cultivated soil, irrigated water and atmospheric conditions. In this study a non-essential metal, aluminum, and some essential metals such as Ca, Fe, K, Mg and P were assessed by ICP-AES in mg/kg on dry weight basis (Table-1). The mean and range of daily intake of nutrients from vegetables for adults are presented in Table-2. There was no significant difference between concentrations of Al in roselle, amaranth and cassava leaves. The lowest concentration of Al was found in cassava sample of PK8 market (11 mg/kg) and the highest concentration in amaranth of Akebe’s market (173 mg/kg). The uptake of Ca was significantly different in three leafy vegetables. The concentration of Ca decreased in the order: amaranth > roselle > cassava. The lowest Ca concentration was in cassava of Mt-Bouet (5897 mg/kg) and the highest Ca concentration was in amaranth of Nzeng Ayong (24911 mg/kg). The lowest concentration was observed in cassava of Okala (135 mg/kg) and the highest concentration in amaranth of Owendo (1220 mg/kg). The mean daily intake of Ca of the leafy vegetables studied varied between 13% and 56% of the recommended dietary allowances (RDA), which confirms that consumption of leafy vegetables is of utmost of importance since horticultural crops may be secondary source of calcium in comparison to dairy products but, taken as a whole, fruits and vegetables account for almost 10% of the calcium in the food supply. The dark green leafy vegetables are potential calcium sources because of their absorbable calcium content (Titchenal and Dobbs, 2007). There was no significant difference in Fe uptake in leafy vegetables. Its concentration varied between 135 mg/kg (cassava of Mt-Bouet) and 1220 mg/kg (amaranth of Owendo market). The estimated daily intake of Fe from consumption of the leafy vegetables studied ranged between 4 to 36 mg/day. The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of Fe is 10-18 mg/day for an adult (Dimirezen and Uruc, 2006). This value was lower than those found for the roselle bought in Okala market (146%) and amaranth of Owendo market (199%). The uptake of K, Mg and P was significantly higher in amaranth than in the other vegetables. Thus, the highest concentrations were found in amaranth of Nkembo (9728 mg/kg), amaranth of NzengAyong (7146 mg/kg) and amaranth of Nkembo (1277 mg/kg) for K, Mg and P, respectively. The lowest concentrations were found in roselle of Mt-Bouet (1531 mg/kg), roselle of Owendo (1470 mg/kg) and cassava of Mt-Bouet (186 mg/kg) for K, Mg and P, respectively. The daily intake of P and K from leafy vegetables studied is the lowest. It is always less than 6% of the RDA. Vicente et al. (2009) indicated that fruit and vegetable contribution to the total phosphorus in the US food supply was an average of 9.5%. But Potassium is the most abundant individual mineral element in vegetables. It normally varies between 600 and 6000 mg/kg of fresh tissue. Leafy green vegetables are known such as potassium-rich vegetables. The daily intake of Mg varied between 43 mg/kg and 210 mg/kg, 10% and 50% of RDA. People who eat of good quantities of green leafy vegetables, nuts, and whole grain breads and cereals ensures a sufficient intake of magnesium and are found to have higher magnesium densities than high-fat users, who consume significantly more servings of meat and higher levels of discretionary fat (Sigman-Grant et al., 2003). Generally, magnesium levels are significantly higher in vegetables than in fruits, but nuts are good sources of this nutrient.

References:

REFERENCES

1. Akbar JF, Ishaq M, Khan S, Ihsanullah I, Ahmad I, Shakirullah M. A comparative study of human health risks via consumption of food crops grown on wastewater irrigated soil (Peshawar) and relatively clean water irrigated soil (lower Dir). Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010; 179: 612-621.

2. Akpabio UD, Akpakpan AE, Enin GN. Evaluation of Proximate Compositions and Mineral Elements in the Star Apple Peel, Pulp and Seed. Journal of basic and applied scientific research 2012; 2: 4839-4843.

3. Batra J, Seth PK. Effect of iron deficiency on developing rat brain. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry 2002; 17: 108-114.

4. Dimirezen D, Uruc K. Comparative Study of trace elements in certain fish, meat and meat products. Meat Science 2006; 74: 255–260.

5. Horbowicz M, Kowalczyk W, Grzesiuk A, Mitrus J. Uptake of aluminum and basic elements, and accumulation of anthocyanins in seedlings of common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) as a result increased level of aluminum in nutrient solution. Ecological Chemistry and Engineering 2011; 18: 479- 488.

6. Jakobsen ST. Interaction between Plant Nutrients. IV. Interaction between Calcium and Phosphate. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B 1993; 43: 6–10.

7. Kawashima LM, Soares LMV. Mineral profile of raw and cooked leafy vegetables edible in Southern Brazil. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2003; 16: 605-611.

8. Lokeshappa B, Shivpuri K, Tripathi V, Dikshit AK. Assessment of Toxic Metals in Agricultural Produce. Food and Public Health 2012; 2: 24-29.

9. Morard P, Pujos A, Bernadac A, Bertoni G. Effect of temporary calcium deficiency on tomato growth and mineral nutrition. Journal of Plant Nutrition 1996; 19 : 115–127.

10. Murray RK, Granner DK , Mayes PA, Rodwell VW. Harper’s Biochemistry, 25th Ed. McGraw-Hill, Health Profession Division, USA; 2000.

11. Nardi EP, Evangelist ES, Tormen L, Saint´Pierre TD, Curtius AJ, de Souza SS, Barbosa Jr F. The use of inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) for the determination of toxic and essential elements in different types of food samples. Food Chemistry 2009; 112: 727-732.

12. Ondo JA, Prudent P, Massiani C, MenyeBiyogo R, Domeizel M, Rabier J et al. Impact of urban gardening in an equatorial zone on the soil and metal transfer to vegetables. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society 2013; 78: 1045–1053.

13. Ondo JA, Prudent P, MenyeBiyogo R, Rabier J, Eba F, Domeizel M. Translocation of metals in two leafy vegetables grown in urban gardens of Ntoum, Gabon. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2012; 7: 5621-5627.

14. Sigman-Grant M, Warland R, Hsieh G. Selected lower-fat foods positively impact nutrient quality in diets of free-living Americans. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2003; 103: 570–576.

15. Soetan KO, Olaiya CO, Oyewole OE. The importance of mineral elements for humans, domestic animals and plants: A review. African Journal of Food Science 2010; 4: 200- 222.

16. Titchenal CA, Dobbs J. A system to assess the quality of food sources of calcium. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2007; 20: 717–724.

17. Vicente AR, Manganaris GA, Sozzi GO, Crisosto CH. Nutritional Quality of Fruits and Vegetables. In, Postharvest Handling: A Systems Approach, Second Edition, Elsevier, Oxford; 2009.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License