IJCRR - 6(22), November, 2014

Pages: 15-18

Date of Publication: 21-Nov-2014

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

Infant and young child feeding practices in an urban underprivileged area in Bangalore, Karnataka, India

Author: Jerome S. N., Catherin N., Sulekha T.

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Introduction: Infant and young child feeding practices constitute a major component of child caring practices. These practices continue to be neglected in spite of their important role in the growth of infants. The prevalence of underweight, stunting and wasting among under-three children was found to be 47%, 45% and 16% respectively in India.

Objective: To assess the infant and young child feeding practices in an urban underprivileged area in Bangalore, Karnataka, India. Methods: It was a cross sectional study conducted in an urban slum area with a sample size of 61 mothers of children aged less than two years. A door to door survey was conducted during November 2012 to January 2013, using a validated questionnaire. Results: The study population comprised of 61 mothers of children aged less than two years. Th15/10/2014e mean age of the mothers was 24.1 \? 3.6 years. Among the study population 52.5% and 82.0% had fed their children with prelacteal feeds and colostrums respectively. Exclusive breast feeding up to six months was practiced by 54.2% of the mothers. Of all of them 59.0% initiated breastfeeding within one hour of birth. Only 41.7% of them started complementary feeds at six months of age. It was observed that 49.2% of the children were under nourished according to WHO (World Health Organization) weight for age growth charts. Conclusion: The study shows poor infant and young child feeding practices with poor nutritional status. There is need for promotion and protection of optimal feeding practices for improving nutritional status of infants.

Keywords: Infant and young child feeding practices, Breast feeding, Nutritional status; India

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Breast feeding is the ideal way of providing food for the growth and development of infants. Infant-feeding practices constitute a major component of child rearing and caring practices.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) had recommended exclusive breastfeeding for every child for the first six months of life with early initiation and also recommended continuation of breastfeeding for first 2 years or more together with nutritionally-adequate, age-appropriate and safe complementary feeding starting at six months of life. 2 The prevailing rates show that early initiation within one hour of birth is 25%, exclusive breast feeding for six months is 46% and appropriate complementary feeding at six months is 57%.3 Also in a study conducted in a West Bengal Slum among 0-6 month age group, 39.6% children were initiated breast feeding within one hour of birth, pre-lacteal feeding was received by 27.1%. Exclusive breast feeding was noted in 52.1% in 0- 6 month of age children. One-fourth infants were bottle-fed and 12.5% received solid or semisolid food before six months. Among 6-23 months of age children, 95.9% children continued breast feeding. Along with this, the study showed 35.9% children underweight and 15.9% severely underweight in the slum setting.4 There are issues such as prelacteal feeding, delayed initiation of breast feeding, denial of colostrums, lack of exclusive breast feeding and several instances of improper weaning practices that lead to a vicious circle of under nutrition which stands at 43% below 3 years of age.3 More than half of all deaths in infants are attributable to under nutrition. Nearly 67% of the child deaths in India are due to the potentiating effects of malnutrition.5 There is a need to reduce infant mortality and improve the level of nutrition in children. The current statistics show that the infant mortality rate (IMR) still continues to be 47 per 1000 live births.6 In India, while the IMR has shown decline there still remains the need to accelerate improvements in infant and neonatal survival to achieve the Millennium Development Goal, to reduce IMR to 27 by 2015.7 One important way to reduce IMR is to ensure 100% exclusive breast feeding for the first six months of life followed by complementary feeding along with continued breast feeding. Recent studies on maternal and child under nutrition has estimated that nearly 1.4 million infant deaths can be prevented with exclusive breast feeding.8,9 The timely introduction of complementary feeding can prevent almost 6% of under-five mortality.10 We conducted this study to assess infant and young child feeding practices in infants below 24 months and their corresponding nutritional status in an urban underprivileged area in Bangalore, Karnataka.

Material and Methods

We conducted a community based cross sectional descriptive study. The criteria for selection was mothers of children within 0 to 24 months who gave consent to participate. The severely ill children and those with metabolic disorders were excluded from the study. Through convenient sampling we had a sample size of 61. Institutional ethical committee clearance was obtained for the study. The data was collected over a period of four months from November 2012 to February 2013. A door to door survey was conducted and 61 mothers were interviewed in Laxman Rao Nagar, Bangalore. Written informed consent was obtained and a validated questionnaire based on the Breast Feeding Promotion Network of India (BPNI) was administered, which has been modified according to our settings along with anthropometric measurements.11 The data was collected under four domains namely demography, antenatal care, feeding practices and anthropometry. The parameters to assess the nutritional status of children were measured and recorded according to standard protocols laid down by the Centre for Disease Control.12 The data was entered into SPSS software version 20.13 Tests of association like chi Square test was done. Under nutrition was assessed as per the WHO standardized growth charts.14 The results were tabulated and conclusions drawn.

Results

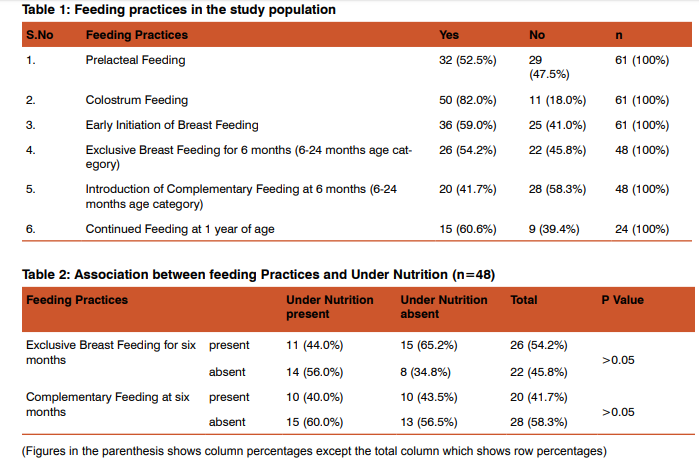

Totally 61 mothers were surveyed and the mean family size was 5.57 ± 2.3 persons with 41% of families falling within the class five socioeconomic scale category. BG Prasad’s social classification was used for the socioeconomic status classification.[15,16] The mean age of mothers was 24.13 ± 3.6 years and 42.6% of them had high school education. The average number of antenatal checkups was 8.02 ± 3.6 times and 82% of the mothers had a normal vaginal delivery. A total of 61 children under 24 months of age were included in the study of which 21.32% were below six months of age, 39.34% of them were within 6-12 months and 39.34% were 12-24 months category. The mean age was 11.59 ± 5.4 months. Of them 52.5% were females and 47.5% were males. In the study population, all the children were breast fed and out of which 52.5% were given prelacteal feeds with sugar water being the predominant prelacteal feed at 56.3%. Initiation of complementary feeding at six months was 41.7% in 6-24 months age group. Of the total study population 44.3% and 26.2% were fed rice with dhal and cerelac as the predominant mode of complementary feeding respectively. Each child received an average of 2.85 ± 0.79 meals per day as a part of complementary feeding. The prevalence of bottle feeding was 21.3%. The mean number of breast feeds in a day for the first six months of life was 7.69 ± 3.9 and 3.69 ± 1.5 during the day and nights respectively. During the next 6-24 months the mean number of feeds decreased to 4.44 ± 3.9 and 2.25 ± 1.9 during the day and night respectively. The feeding practices are shown in table 1. Of the study population 50.8% of the children had an episode of diarrhoea within two weeks prior to the survey and of which 41.9% of them received less than normal breast feeding during the period of illness. The prevalence of under nutrition, stunting and wasting was 49.2%, 60.7% and 31.1% respectively. Overall 22.6% of the children had severe under nutrition. There was no statistically significant association between income of the families, education of the mother and number of antenatal checkups with the infant feeding practices. There was no statistically significant association between the feeding practices and the nutritional status of the study group. The association between feeding practices and under nutrition is shown in table 2.

Discussion

In our study prelacteal feeding was given to 52.5% of the infants which is comparable to National Family Health Survey – 3 (NFHS-3) data (57.3%).2 However a similar study done in West Bengal showed 27.1%.3 The reasons could possibly be due to the prevailing tradition in the slum thereby exerting harmful effects on the infants.17 Colostrum was refused to 18% of the infants which is lower when compared to a study done in Allahabad where 54.8% of the mothers discarded colostrum. In the same study lack of colostrum feeding was associated with increased risk of under nutrition.18 Early initiation of breast feeding within one hour was followed by 59% of the respondents and studies have showed that early initiation of breastfeeding could reduce neonatal mortality by 22%.19 Exclusive breast feeding rate for the first six months among the infants within 6-24 months was 54.2% which throws light on the feeding practices pre-vailing in the urban slum. Though it is low the situation is better as compared to NFHS-3 which put the all India average at 46.4%.3 This could be attributed to the poor knowledge about optimal breast feeding practices. Another reason could be due to inadequate milk secretion by the mother as found by a study in rural Tamilnadu by Parmar et al.20,21 Promotion of exclusive breast feeding would go a long way in improving infant survival.8,9 The timely initiation of complementary feeding at six months was 41.7% in the 6-24 months age group which was much lower than Dehradun study (70.1%) but significantly better than 16.6% observed in Delhi slums.22,23 The mean number of complementary feeds per day was 2.85 + 0.79 which is close to the (Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness) IMNCI recommendations.24 Complementary feeds bridge the energy gap, vitamin A gap and iron gap which arises in breastfed infants at six months.25 Thus there is a need to optimize the complementary feeding practices in the urban slum. Breastfed children at 12-23 months receive 35-40% of their total energy needs from breast milk thus emphasizing the need for continued breast feeding till two years of age.25 Continued breast feeding at one year was 60.6% in the12-24 month age group which is low. The prevalence of diarrhoea among the study group was 50.8% in the preceding two weeks of the survey which again could be attributed to increased patronage of prelacteal feeds, supplementary feeds like formula milk, bottle feeding (21.3%) and poor hygiene. Of all 41.9% mothers fed less than the usual number of breastfeeds during the period of illness which could predispose the child to under nutrition. Mortality related to diarrhoea mostly occurs in developing countries, and the highest rates of diarrhoea occur among malnourished children.26 The feeding practices though not significant statistically with under nutrition in our study, had been statistically significant in another study conducted by Dinesh Kumar et al.1

Conclusion

Optimized infant and young child feeding practices are the best way to improve child survival. Urgent steps are needed to ensure improved and optimal infant feeding practices which will help overcome the burden of Infant mortality and morbidity. Better perinatal counselling by health professionals and continued emphasis on feeding practices during immunization visits would be beneficial.

Acknowledgement

Authors acknowledge the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. The authors are also grateful to authors / editors / publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed.

References:

1. Dinesh Kumar, Goel NK, Poonam C, Mittal, Purnima Misra. Influence of Infant-feeding Practices on Nutritional Status of Under-five Children: Indian J Pediat 2006 May 73: 417- 22

2. World Health Organization. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. 41

3. National Family Health Survey -3, IIPS, 2005-06

4. Mukhopadhyay DK, Sinhababu A, Saren AB, Biswas AB. Association of child feeding practices with nutritional status of under-two slum dwelling children: A communitybased study from West Bengal, India. Indian J Pub Heal 2013; 57:169-72.

5. Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA Jr, Schroeder DJ, Habicht JP. The effects of malnutrition on child mortality in developing countries. Bull Word Health Organ 1995;73: 443-8.

6. Registrar General of India. Sample Bulletin, Sample Registration System; 2011. Available from: http://www.pib. nic.in/archieve/others/2012/feb/d2012020102.pdf. Accessed on 29 Oct 2014.

7. Millennium Development Goals- India Country Report 2009, Mid-term Statistical Appraisal, Central Statistical Organization, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. http://www.in.undp. org/content/india/en/home/mdgoverview/ Accessed on 14 Oct 2014

8. Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 2008 Jan; 371:243-60.

9. Bhutta ZA, Tahmeed A, Black RE, Cousens S et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet 2008 Jan; 371:417-40.

10. Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS; Bellagio Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet 2003;362:65-71

11. http://www.bpni.org Accessed on 5 Oct 2012

12. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), Anthropometry Procedures Manual; Jan 2007 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs /data/nhanes /nhanes_ 07_08/manual_an.pdf Accessed on 5 Oct 2014

13. SPSS Software; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SPSS Accessed on 5 Oct 2014

14. Child Growth Standards;Available from: http://www. who.int/childgrowth /standards/chart_catalogue/en/ Accessed on 5 Oct 2014

15. BG Prasad score: www.prasadscaleupdateweekly.com Accessed on 12 Oct 2014.

16. BG Prasad Score: www.labourbureau.nic.in.htm Accessed on 12 Oct 2014.

17. Martines JC, Rea M, De Zoysa I. Breast feeding in the first six months. BMJ 1992;304:1068-9.

18. Dinesh Kumar, N.K. Goel, Poonam C. Mittal and Purnima Misra - Influence of Infant-feeding Practices on Nutritional Status of Under-five Children. Indian J Pediat 2006; 73 (5): 417-21.

19. Edmond KM, Zandoh C, Quigley MA, Amenga-Etego S, Owusu-Agyei S, Kirkwood BR. Delayed breastfeeding initiation increases risk of neonatal mortality. Pediatrics 2006;117:380-6.

20. Radhakrishnan S, Balamuruga S S. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding practices among rural women in Tamil Nadu. Int J Health Allied Sci 2012;1:64-7

21. Parmar VR, Salaria M, Poddar B, Singh K, Ghotra H, Sucharu. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding breast feeding at Chandigarh. Indian J Pub Heal 2000;44:131-3.

22. Dr. Vartika Saxena , Dr. Praveer Kumar. Complementary feeding practices in rural community: A study from block Doiwala district Dehradun. Ind J Basi App Medi Resear; March 2014:3(2); 358-63.

23. Sethi V,Kashyap S,Sethi V:Effects of Nutritional Education of mothers on Infant feeding practices.Indian J Pediat 2003,70:463-6.

24. India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Integrated management of Neonatal and childhood illness. Training module of health workers. New Delhi: Ministry of health and Family welfare, Government of India 2003,74-5

25. World Health organization. Global forum for child health research: a foundation for improving child health. Switzerland, Geneva, WHO, 2002.

26. Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet 2003;361: 2226-34.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License