IJCRR - 7(14), July, 2015

Pages: 27-34

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

EFFECT OF HEALTH EDUCATION ONMENSTRUAL HYGIENE AND HEALTHSEEKING BEHAVIOUR AMONG RURAL AND URBAN ADOLESCENTS

Author: Ibanga Ekong

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Introduction: Health promotion programmes presume that providing knowledge about causes of ill health will go a long way towards promoting a change in individual behaviour, towards more beneficial health-seeking behaviour. However, there is growing recognition that providing education and knowledge is not sufficient in itself to promote a change in behaviour. Hence, this study sought to determine how health education could change the menstrual hygiene practices and health seeking behaviour of rural and urban school-going adolescent girls in South-south Nigeria. Materials and Methods: This was a comparative-interventional study conducted among 601 girls using a structured questionnaire and focus group discussion. Sample selection was by multi-stage techniques of stratification and simple random sampling. Intervention was done using health education. Results: More use was made of tissue paper among both groups of respondents after health education (rural 34.1% from 29.3%, urban 16.4% from 14.7%, the observed differences were statistically significant pre- and post intervention{X2= 17.485; 23.132. p= 0.000; 0.000 respectively}). Discussion/Conclusion: This corroborates other study findings that Nigerian girls prefer the use of tissue paper perhaps due to economic realities. The implication of the use of tissue paper is that it could act as culture medium for microbes with its sequelae.

Keywords: Menstrual hygiene, Adolescent girls

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Health information seeking is defined by Tardy and Hale as the search for and receipt of messages that help ‘‘to reduce uncertainty regarding health status’’ and ‘‘construct a social and personal (cognitive) sense of health’’.1 Lambert et al regard seeking information about one’s health as being increasingly documented as a key coping strategy in healthpromotion activities and psychosocial adjustment to illness.2 Health promotion programmes worldwide have long been premised on the idea that providing knowledge about causes of ill health and choices available will go a long way towards promoting a change in individual behaviour, towards more beneficial health-seeking behaviour. However, there is growing recognition, in both developed and developing countries, that providing education and knowledge at the individual level is not sufficient in itself to promote a change in behaviour, as was observed by MacKian.3 Aniebue, Aniebue and Nwankwo, Singh et al and Durge et al, in their studies agree to the importance of educating adolescent girls about their reproductive health which they also perceive as gaining momentum in India during the past few years.4,5,6 Lee et al, Adinma and Adinma, Poureslami and Osati-Ashtiani, and Severino and Moline, have each observed that teachers and formal education in general have little roles to play as source of information on reproductive health7,8,9,10 a situation considered worrisome in view of the important position of teachers as formal instructors in the teaching process of the growing adolescent. Furthermore, as reported by Drakshayani et al, Fakeye and Egade, Beek, Johnson, and Klein and Litt11,12,13-15 education is the single most effective method that will lead to a decrease in the severity of menstrual pain and a reduction in the rate of absence from school. On the other hand, Levisohn expresses his doubt thus: ‘...little is known about the effect of health education intervention on how adolescent girls manage their menstrual hygiene’.16 In an Eastern Nigerian study by Adinma and Adinma,8 it was noted that of the 401 respondents who claimed to have discussed their medical problems associated with menstruation, the most common person with whom this was done was the mother who accounted for 47.1%. A similar observation was made by Lee et al7 who reported that mothers constituted the source of information on menstrual disorders in as high as 80%, in their study population, other studies by Drakshayani et al, Koff et al and Tiwari et al11,17,18 report the mother as the most common source of information on menstruation generally. They go on to comment that the observation was not surprising since mothers are often the closest informant and “teacher” of the growing adolescent girl, and this was probably responsible for the glaring similarity in menstrual attitudes between mothers and their daughters following studies on the “generational differences in perception of menstruation and attitudes to menstruation” conducted by Strauss et al.19 Dongre et al in their study noted that after a health education intervention among currently menstruating girls, ready-made pad users increased significantly, from 5.2% to 24.9%.20 Conversely, cloth users declined from 94.8% to 72.7%; the practice of taking a bath during menstruation was almost universal. The percentage of adolescent girls observing dietary restriction during menstruation showed marginal decline (20.7% to 16.6%). Reusing cloth declined from 84.8% to 57.1%. Notably, among the re-users of cloth, the practices of washing it with soap and water and sun drying increased from 86.2% to 94.2% and 78.4% to 90.05 respectively. Similarly, the results of recent studies by Drakshayani et al, Fakeye and Egade, Dagwood, Nafstad et al, and Westhoff and Davis 11,12,21-23 showed the effectiveness of educating female students about menstrual health topics in both urban and rural schools. Swasthya, a Delhi based NGO reported some improvement in menstrual hygiene behaviour through health education messages disseminated by community-based health workers in rural Delhi.24 Chiou et al in an urban study in Taiwan after introducing self-care pamphlets on dysmenorrhoea and assessing the participants, revealed an increased knowledge and self-care behaviour among them.25 This is consistent with a study by Dongre et al who reported a significant improvement in both the hygiene management of menstruation and health-seeking behaviour of their study participants in rural India after a health education intervention.20 Rankin and Stallings from their study observed that knowledge is a factor that increases patients’ participation and the ability to make informed decisions about health;26 and Carson impresses that making informed decisions is an ongoing and changing process.27 Ahmed has stated that learning about hygiene during menstruation is a vital aspect of health education for adolescent girls.28Educational programmes can increase awareness about reproductive health, but in the absence of appropriate health services, this awareness may not always translate into appropriate help-seeking by adolescents.29 Banister and Schreiber have imposed the responsibility of providing comprehensive and practical information on essential issues of pubertal development on parents, to be assisted by schools and other social institutions.30 The phrase ‘spiral of decision making’ which refers to the process of self-assessment, help-seeking behaviour and new self-assessment is improved with health education.26 A needs framework has been identified in four steps by an Indian study by Barua and Kurz, thus: it begins with a symptom being identified by the girl, creating a felt need for treatment; telling a family member about the need; agreement on the part of family member(s) that it is worth seeking treatment; and action taken by the family and health providers to seek and provide treatment.31 The ability to recognize a symptom, and positive family support could be enhanced by health education. This study sought to determine how health education could change the menstrual hygiene practices and health seeking behaviour of adolescent girls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a comparative interventional study design among adolescent secondary school girls in rural and urban areas. This study was conducted in Akwa Ibom State comprising thirty one (31) local government areas, 24 rural and 7 urban.32 With a population of 3,920,051,33 the population of adolescents, who make up about 23% of the population, is estimated to be 901,612. Using a male/female ratio of 1.09:1, the estimated population of adolescent girls is 431,393 which is the study population. There are about 243 public post-primary institutions in Akwa Ibom State34 and the study subjects were in-school adolescent girls who had attained menarche. Adolescent girls from secondary schools in the selected rural and urban local government areas of Akwa Ibom State took part in this study. A minimum sample size of 546 was calculated. To allow for 10% (i.e. 55) invalid, incomplete and non-responses, the to-tal sample was 546+55= 601 for the four locations giving an average of 150 students per location. This study used both quantitative and qualitative research methods. It consisted of a baseline survey to determine the menstrual hygiene and health-seeking behaviour for menstrual problems of adolescents in the rural and urban areas of this study. The sampling frame consisted of adolescent girls attending the 237 co-educational and girls’ school from the list of rural and urban secondary schools in Akwa Ibom State. Health education intervention on menstrual hygiene and health-seeking behaviour was given to the participants at the end of the baseline survey and another survey was conducted three months post intervention on all the sites. They were compared thereafter to assess the impact of the intervention on menstrual hygiene and health-seeking behaviour between either group (rural and urban) of adolescent girls. The study sought to determine if the intervention had any effect and whether there were rural-urban differences in the observed effect. A multi-stage sampling technique was used to select the study sample. The first stage involved the stratification of local government areas into rural and urban (seven out of the thirty one local government areas in Akwa Ibom State are classified as urban, the other twenty four are rural).32 Two local government areas were selected from each stratum using the simple random sampling technique, by use of table of random numbers. In the second stage, among the thirty eight secondary schools (co-educational and girls’) that were listed in the four local government areas, one school each was selected per local government area (total of 4) using the simple random sampling technique, by use of table of random numbers, after stratification had been done. In the third stage, each school was stratified into lower (31) and upper (42) senior secondary classes to represent junior and senior adolescents. Selection of the classes was by stratified and then simple random sampling, using the table of random numbers, within each strata. The fourth stage involved selection of eligible students (2,867) that met the inclusion criteria (in-school girls aged between 10-19 years who had attained menarche) distributed over the selected streams of each class by the simple random sampling technique by use of table of random numbers. In the use of table of random numbers, every list was itemized. Six hundred and one adolescent girls were selected. A forty eight item questionnaire was designed in line with the specific objectives, with a few aspects adapted from literature review. 35 Pre-test was carried out in a rural girls’ school and an urban girls’ school after the study sites had been selected. At each site, Junior Secondary class 3 (10) and Senior Secondary class 1 (10) female adolescents were involved at this stage. The outcome led to the re-phrasing of certain terms in the questionnaire, and in the derivation of topics for the intervention workshop. Data collection was carried out at the school site during school hours, during the break period, with informed consent from the respective school principals. Pre-tested self-administered questionnaires, following an anonymous respondent approach were shared to the selected students (who had gathered at the assembly hall) without the presence of teachers and male students. The questionnaire sought for information about demographic variables, perception of menstrual problems, types of menstrual problems, coping strategies, sources of help for menstrual problems, and motivation and barriers to health-seeking behaviour. Three female registrars were trained to assist with the conduct of the survey, confidentiality, procedures for responding to students’ questions and focus group discussions. Two Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were conducted to generate qualitative data, regarding the perception, attitude and practices of adolescent secondary school girls as it concerns menstruation. These were conducted by the researcher’s female colleagues. Six girls (including those who had been noted by teachers to be absent from school at various times due to menstrual problems) each from one rural, and from one urban site were engaged in the FGD. The intervention was by Information, Education and Communication (IEC) in which teaching and learning were approached through creative and involving methods. The researcher appropriately educated the girls on what normal menstruation is, in adolescents. They were also educated about proper menstrual hygiene. They were shown pictograms on the types of padding for menstrual flow and either a correct sign or a wrong sign beside a particular item. Proper health-seeking behaviour was taught them, emphasising the benefits of seeking healthcare early and through the right channel, providing the information in a way that was acceptable to them by using cardboards to illustrate the available and suitable avenues. This would empower them to take decisions, modify behaviour and change their social conditions. It took the form of a workshop. A twenty-minute presentation was made followed by a question and answer session. Three student health teams were formed to brainstorm on given topics (derived from the pre-test) and come out with resolutions which each team leader presented to all participants. After the presentation, the researcher made the necessary corrections. The entire session did not exceed one hour. Finally, hand-bills on menstrual problems and health-seeking behaviour were distributed to all the participants, and they were encouraged to share them with other peers. Quantitative data generated from the survey was entered into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software, Version 17 for Windows, and analyzed. Percentages were calculated to draw out differences in variables between urban and rural adolescent girls. Cross tabulation and Chisquare tests were used to determine any association between selected socio-demographic variables, and perception and health-seeking behaviour variables. Odds ratio, Chi square and t test were used to compare possible differences between urban and rural variables and significance was 0.05 at the 95% confidence level. Tables were used to highlight the results obtained. Qualitative data gathered through Focus Group Discussions, and the interview following the mystery-client approach were transcribed verbatim from the audio record and analyzed manually. The check-list was also analyzed manually. Ethical clearance was received from Ethical Committee of the University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, while approval was obtained from the Ministry of Education and the respective school authorities. Informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians of participating students for minors; and from students that had attained the age of 18. Audio records were made with due verbal consent from the participants. Anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents were maintained in all phases of the study. Due to the sensitive nature of the study, female assistants were used at all times in administering the quantitative and qualitative surveys. Informed consent was sought from participants with respect to voluntary participation and freedom to discontinue the interview/discussion at any stage. There were anticipated benefits of improved behaviour and social conditions derived from the intervention in the short term. Free consultation was given to those with menstrual problems. There were no risks to the participants in the study. Out-of-school adolescent girls may have different perceptions and practices about menstruation; hence the study findings may only be generalizable for in-school adolescents in similar socio-demographic contexts. Increased knowledge is not necessarily a sufficient cause for behaviour change; other factors (e.g. culture, beliefs, inhibition) may affect the possible benefits derived from the intervention in the long term.

RESULTS

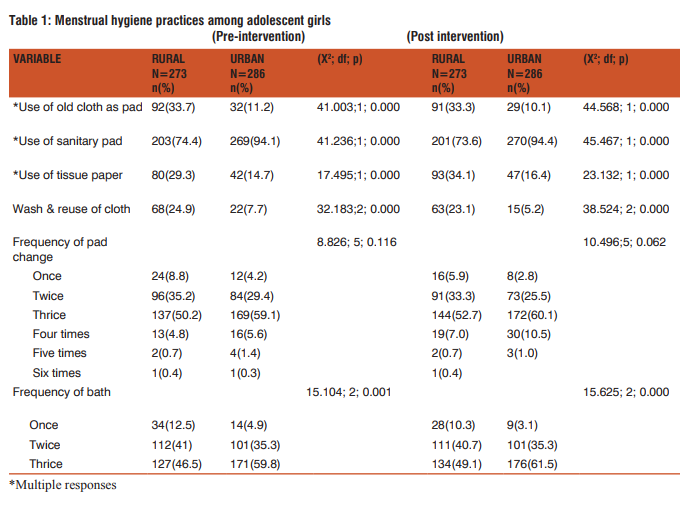

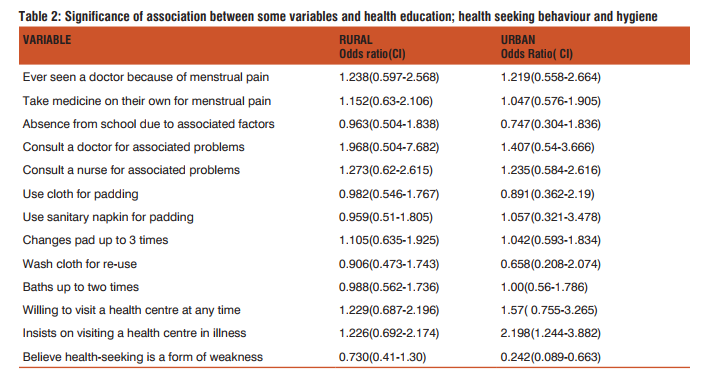

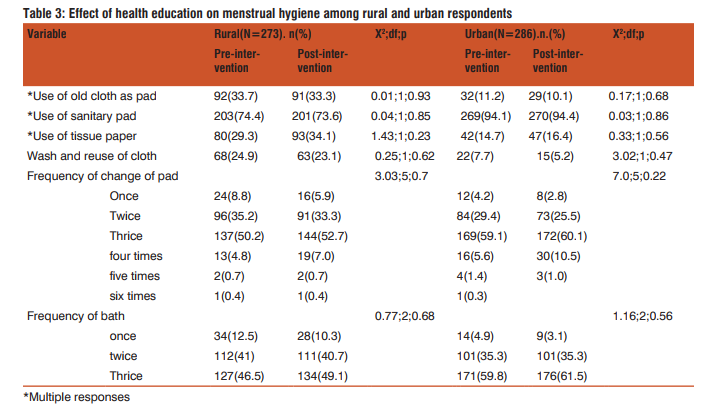

Table 1 displays the state of menstrual hygiene before and after health education among rural and urban respondents. There were some noted improvements in menstrual hygiene after health education was given: 33.3% rural and 10.1% urban respondents used old cloth as sanitary pad as against the previous 33.7% rural and 11.2% urban respondents respectively (the observed differences pre- and post-intervention were statistically significant {X2 = 41.003; 44.568. p= 0.000; 0.000} respectively), however the proportion of rural respondents that used sanitary pad was observed to reduce (74.4% to 73.6%) after health education as against the increased proportion (94.4% from 94.1%) of urban respondents (observed differences pre- and post-intervention were also statistically significant {X2 = 41.236; 45.467. p= 0.000; 0.000} respectively); more use was made of tissue paper among both groups of respondents after health education (rural 34.1% from 29.3%, urban 16.4% from 14.7%, the observed differences were also statistically significant pre- and post intervention{X2 = 17.485; 23.132. p= 0.000; 0.000 respectively}); also, there was a reduction in the proportion of both group of respondents who washed and reused cloth used as pad (rural 24.9% to 23.1%, urban 7.7% to 5.2%, again the observed differences were also statistically significant pre- and post intervention{X2 = 32.183; 38.524. p= 0.000; 0.000 respectively}). With regards to the frequency of change of pad among respondents, there was a general improvement to 3-4 times daily change after health education was given (the observed rural-urban differences was statistically not significant post intervention{X2 = 10.496, p= 0.062}). There was an increased proportion of respondents among both groups who stepped up their frequency of bath to three times (rural 49.1% from 46.5%; urban 61.5% from 59.8%). The observed rural-urban differences were statistically significant pre- and post intervention{X2 = 15.104; 15.625. p= 0.001; 0.000 respectively}. Table 2 displays the significance of association, using odds ratio (OR) at 95% Confidence Interval (CI), between some variables (health-seeking behaviour & hygiene) and exposure to health education. The association between health education and belief in the urban area that health-seeking behaviour is a weakness showed that the effect was statistically significant in the urban areas (OR=0.242, CI: 0.089-0.663). No association of statistical importance was observed in the health-seeking behaviour and menstrual hygiene variables. Table 3 displays the effect of health education on menstrual hygiene within rural, and then urban respondents. Although there were some marginal improvements in some menstrual hygiene variables, no statistically significant association was however observed in this study.

DISCUSSION

The rural discussants during the focus group interview had said they could use all sorts of items e.g. beret in emergen-cies while their urban counterparts admitted they used old cloth/parts of school uniform during emergencies. There were some noted improvements in menstrual hygiene after health education was given: where urban respondents using old cloth as sanitary pad reduced more than the rural respondents (observed rural-urban difference was statistically significant). This is in keeping with findings in an Indian study in which the use of old cloth reduced but ready-made sanitary pad use increased;20 however, the proportion of rural respondents that used sanitary pad was observed to reduce after health education (perhaps due to cost) as against the increased proportion by urban respondents; more use was made of tissue paper among both groups of respondents after health education also, this corroborates two Nigerian study findings that Nigerian girls prefer the use of tissue paper,36,8 perhaps due to economic realities. The implication of the use of tissue paper is that it could act as culture medium for microbes which may result in serious infection and its sequelae. Good enough, there was a reduction in the proportion of either group of respondents who washed and re-used cloth used as pad (observed rural-urban difference was statistically significant in favour of the urban girls), also in keeping with Dongre’s findings.20 With regards to the frequency of change of pad among respondents, there was a general improvement to 3-4 times daily change after health education was given, but the observed rural-urban difference was not statistically significant in this study. There was also an increased proportion of respondents among either group who stepped up their frequency of bath to three times daily (observed rural-urban difference was statistically significant in favour of the rural girls), though it has been stated to be a universal practice.20 The rural discussants during the focus group interview had said they could use all sorts of items e.g. beret in emergencies while their urban counterparts admitted they used old cloth/parts of school uniform during emergencies. Both groups often washed and re-used these items. The inadequacies of school toilet facilities for girls, and an improperly timed menstruation cycle were stated as some of the reasons for the use of any item that came handy. There was no statistically significant association between health education, and menstrual hygiene and health-seeking behaviour among the respondents. This means that there was no statistically significant difference among respondents pre-intervention and post intervention. Probably, the sample size may have been small or being that it was provided once it might not have been enough to make the desired impact. Also three months might not have been enough time for impact to be made. It implies that when planning an intervention of this nature for in-school adolescents in Akwa Ibom State, the researcher or other researchers would need more than a onetime intervention or the method used may need to be change.

CONCLUSIONS

• The effect of the intervention may not have been statistically significant with respect to menstrual hygiene and health-seeking behaviour. It however does not preclude real effect of public health importance as seen in the positive changes in frequency of noted variables

Recommendations

• Mothers and other female adults ought to imbibe the culture of educating younger girls on correct menstruation issues even before they attain menarche

• Barriers to health seeking should be delineated and corrected

• There is a need for the government to put policies in place for early health education to be taught in schools

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Author acknowledges the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. The author is also grateful to authors/ editors/ publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed.

References:

1. Tardy and Hale, 1998, p. 338. In: Cotten SR and Gupta SS. Characteristics of online and offline health information seekers and factors that discriminate between them. Social Science and Medicine. 2004; 59(9):1795–806.

2. Lambert SD, Loiselle CG. Health information-seeking behaviour. Qualitative Health Research. 2007; 17(8): 1006-1019.

3. MacKian S. A review of health seeking behaviour: problems and prospects. University of Manchester Health Systems Development Programme. 2002. Internal paper No. HSD/WP/05/03.

4. Aniebue UU, Aniebue PN, Nwankwo TO. The impact of premenarcheal training on menstrual practices and hygiene of Nigerian school girls. Pan African Medical Journal 2009; 2: pp9.

5. Moronkola OA and Uzuegbu VU. Menstruation: Symptoms, management and attitude of female nursing students in Ibadan, Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health 2006; 10(3): 84-89

6. Durge PM, Varadpande U. Impact of assessment of health education in adolescent girls. J Obst Gyn India 1995;41:46-50.

7. Sharma A, Taneja DK, Sharma P, and Saha R. Problems related to menstruation and their effect on daily routine of students of a medical college in Delhi, India. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health 2008; 20(3): 234-241.

8. Adinma ED, Adinma JIB. Perceptions and practices on menstruation amongst Nigerian secondary school girls. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 2008; 12(1): 74-83.

9. Poureslami M and Osati-Ashtiani F. Attitudes of female adolescents about dysmenorrhoea and menstrual hygiene in Tehran suburbs. Arch Iran Med 2002; 5: 219-24

10. Severino SK, Moline ML. Premenstrual syndrome identification and management. Drugs. 1995; 49: 71 – 82.

11. Singh MM, Devi R and Gupta SS. Awareness and health seeking behaviour of rural adolescent school girls on menstrual and reproductive health problems. Indian Journal of Medical Sciences 1999; 53:439-43.

12. Fakeye O, Adegoke A. The characteristics of the menstrual cycle in Nigerian schoolgirls and the implications for school health programmes. Afr J Med Med Sci 1994;23:13-7.

13. Beek JS. Puberty and Dysmenorrhea Treatment. Novice’s Gynecology. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins; 1996: 771 – 80.

14. Johnson J. Level of knowledge among adolescent girls regarding effective treatment for dysmenorrhea. J Adolesc Health Care. 1988; 9: 398 – 420.

15. Klein JR, Litt IF. Epidemiology of adolescent dysmenorrhea. Pediatrics. 1981; 68: 54 – 63.

16. Loevinsohn BP. Health education interventions in developing countries: a methodological review of published articles. International Journal of Epidemiology 1990; 9(4):788-94.

17. Koff E and Rierdan J. Preparing girls for menstruation: recommendations from adolescent girls. Adolescence 1995; 30 (20): 795-811.

18. Tiwari H, Oza UN, Tiwari R. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about menarche of adolescent girls in Anand district, Gujarat, India. East Mediterr Health J. 2006; 12 (34): 428-433.

19. Strauss B, Appelt H, Daub U, de Vries I. Generational differences in perception of menstruation and attitude to menstruation. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 1990 Feb; 40(2): 48-56.

20. Dongre AR, Deshmukh PR, Garg BS. The effect of communitybases health education intervention on management of menstrual hygiene among rural Indian adolescent girls. World Health & Population 2007; 9(3): 48-54.

21. Dagwood MY. Dysmenorrhea. J Reprod Med. 1995; 30: 154 – 67.

22. Nafstad P, Stray-Pedersen B, Solvberg M, et al. Menarche and menstruation problems among teenagers in Oslo [in Norwegian]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1995; 115: 604 – 6.

23. Westhoff CL, Davis AR. Primary dysmenorrhoea in adolescent girls and treatment with oral contraceptives. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2001; 14: 3-8.

24. International Centre for Research on Women. Improving the reproductive health of married and unmarried youths in India 2006. http://www.icrw.org/docs/publications-2006/R-3_new. pdf. Accessed on 27/05/2010.

25. Chiou MH, Wang HH, Yang YH. Effect of systematic menstrual health education on dysmenorrhoeic female adolescents’ knowledge, attitudes, and self-care behaviour. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences 2007; 23(4): 183-90.

26. Rankin SH and Stallings KD. Patient education: Issues, principles and practices. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott; 1990.

27. Carson AJ. ‘What brings you here today?’: The role of self-assessment in help-seeking for age-related hearing loss. Journal of Aging Studies. 2005; 19(2): 185–200.

28. Ahmed SM. Differing Health and Health-Seeking Behaviour: Ethnic Minorities of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. Asia Pac J Public Health 2001; 13(2): 100-8.

29. Joshi BN, Chauhan SL, Donde UM, Tryambake VH, Gaikwad NS and Bhadoria V. Reproductive health problems and help seeking behavior among adolescents in urban India. Indian J Pediatr 2006; 73 (6):509-513.

30. Banister E and Schreiber R: Young women’s health concerns: Revealing paradox. Health Care for Women International 2001; 22:633-647.

31. Barua A and Kurz K. Reproductive health-seeking by married adolescent girls in Maharashtra, India. Reproductive Health Matters. May 2001; 9(17).

32. Okon MI. Geographical analysis of urban-rural fertility differentials in Akwa Ibom State. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Uyo, Uyo. 2008.

33. Federal Republic of Nigeria. Report on the Census 2006 Final Results. Official Gazette; Abuja. 2nd February, 2009.

34. List of public secondary schools in Akwa Ibom State. Directorate of secondary/higher education, Ministry of Education, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. April, 2007.

35. Sule ST and Ukwenya JE. Menstrual experiences of adolescents in a secondary school; J Turkish-German Gynecol Assoc. 2007; 8(1):7-14.

36. Omigbodun OO and Omigbodun AO. Unmet need for sexuality education among adolescent girls in southwest Nigeria: A qualitative analysis. African Journal of Reproductive Health 2004; 8(3): 27-36.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License