IJCRR - 7(1), January, 2015

Pages: 09-12

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

DEMOGRAPHIC AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC CORRELATES OF ACUTE UNDER-NUTRITION IN THE PRE-SCHOOL CHILDREN OF ALLAHABAD, NORTH INDIA

Author: Urvashi Sharma, Neelam Yadav, Rachana, Shweta Mishra, Pankaj Tiwari

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Objective: To study the socio-demographic risk factors for the malnutrition in the pre-school children (4-6 years) of Allahabad. Method: 425 children were surveyed in the study belonging to both the rural and urban parts of the district. Results: Of the total children studied, there was an almost equal proportion of (50%) of boys and girls. Most of the children belonged to rural habitat (66.3%). Cases of low weight-for-age (underweight -2SD) were found to be 63.5% of the total studied

population, whereas 39.8% children were low weight- for-height (wasted -2SD).

Conclusion: Parent's education, per capita income, family size and type of settlement were the key variables identified as risk

factors for under nutrition in pre-school children.

Keywords: Under nutrition, Socio demographic, Risk factors

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

The initial years of life are a phase of critical physical, mental and psychological growth and development of a child. As pre-schoolers are one of the most easily susceptible and vulnerable group of any community, their health status works as a valuable indicator of the community’s nutritional status [1]. Any sort of nutrient deficit in this period may prove growth limiting which may eventually increase the burden of childhood morbidity and mortality. About 50 per cent of all child deaths is associated with malnourishment and is ascribed to the diarrhea, respiratory infections, measles, and other clinical conditions[2].The results of six studies done by World Health Organization (WHO), a strong association was established between severity of weight-for-age deficits and mortality rates as 54 per cent deaths of under five children in developing countries were accompanied by low weight for age [3].Even micronutrient deficiencies precipitates out in a malnourished children like that of vitamin A[4], Zinc[5] and other co-morbidities [6] .Thus, there emerges an acute necessity of evaluating and eventually exterminating the root causes and risk factors which are playing a significant role in the occurrence of malnutrition.

METHODS

The study was carried out in both the rural blocks and urban wards of the Allahabad district from March to July 2012. All the children recruited for this descriptive study were between 48 to 72 months of age. Data collection was done by a structured interview guided by a pretested questionnaire. Children registered at anganwadi centers of the villages (blocks) and various governmental schools of the urban wards were recruited as the respondents along with the presence of either of the parents. Anthropometric measurements, dietary pattern, nutrient intake and assessment of socioeconomic status were done. Anthropometry was done by trained anthropometrists using standard methods [7]. Z-scores (weight-for-age, heightfor-age, and weight-for-height) were calculated using WHO recommended growth curves [8]. Height and weight were recorded to the nearest 0.5 kg and 0.5 cm respectively by standard methods [7]. Nutritional status classification was done as per the cut off’s given by WHO [9]. Statistical Analysis: Univariate analysis by Chi-square test was used to measure the association of the characteristics with the outcome and logistic regression was used to explore the possibility of the interactions. Software Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 12.0 was used for statistical analysis. Ethical Issues: A written and informed consent was taken from the respondent’s parents. All the participants had an option to opt out of the study at any time during the data collection. The study was approved and registered by the Doctoral Program Committee of the University of Allahabad. The study protocol was approved by the ‘Institutional Ethical Committee Review Board’ (IERB) of Population Resource and Research Centre (PPRC), Kamla Nehru Hospital, Allahabad.

RESULTS

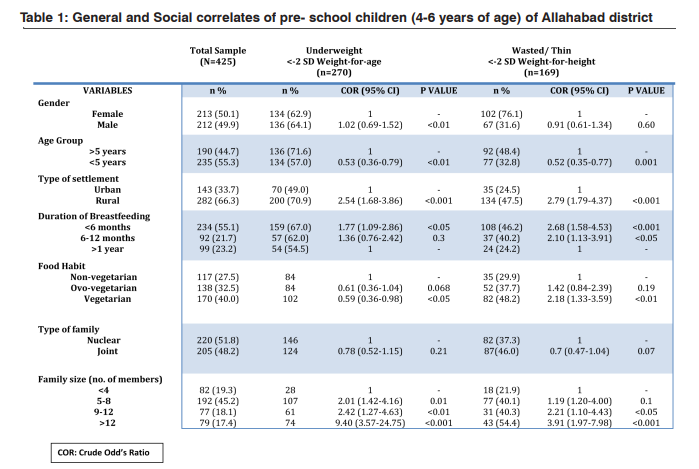

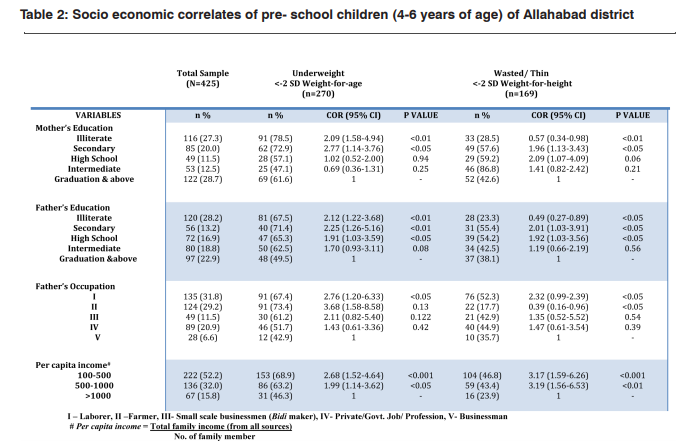

Out of the total children studied 44.7%were above 5 years (<72 months) and 55.3% belonged to the age group of under 5 (<60 months) (Table:1). The majority of the children 55.1% did not receive 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding while almost an equal no. of children 21.7% and 23.2% were breastfed till the age of 6-12 months and 1 year respectively. Non vegetarians were least in number 27.5% as compared to that of the ovovegetarians (32.5%) and vegetarians (40.0%). Most of the children (48.2%) belonged to the family size of 5-8 members. On examining the educational status of the parent’s majority of the mothers were graduates 28.7% but unfortunately following closely to this number were 27.3% of the illiterate mothers who never received any formal schooling (Table:2). Fathers generally being the earning member of the family largely were found to be illiterate (28.2%). Occupation wise, maximum percentage of the fathers were peasants or laborers (31.8%) followed by farmers (29.2%), then by Job or professionals (20.9%), small scale businessmen (11.5%) and lastly big business holders (6.6%)

DISCUSSION

We have studied the associated risk factors for the prevalence of malnutrition (48-72 months of age). The magnitude of the associative factors influencing the occurrence of malnutrition is very useful in gauging their potential role while planning the nutritional intervention programs. Underweight gives us the picture about the corporal mass with respect to the age. It is a prominent measure of the acute malnourishment as this index includes the rapid changes in weight [10]. Weight-forheight (Wasting) is a measure of “Thinness” which signifies both acute and chronic under-nutrition, owing to the fact that this index takes into account the height of an individual accompanied by a recent weight loss. It was found that female gender was more strongly related to the underweight (p<0.01) [11] but not to thinness. Older children (60-72 mo.) showed a higher incidence of underweight (p<0.01).(Table:1). Children belonging to rural and background were 2.54 and 2.79 times more likely to be underweight and wasted respectively (p<0.001). It was also observed that children who got less than six months of breastfeeding were slightly at more risk of being underweight (p<0.05) and thin (p<0.01) substantiating the fact that prolonged breastfeeding may prove to be protective against acute and chronic malnutrition. Children who got less than 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding were more underweight (p<0.05) as compared to those who got more or up till 6 months or 1 year of the breastfeed. However, this status worsened in case of wasted children where the chances of developing wasted was more than doubled in the children who were less than 6 mo. (p<0.01) and up till 6 mo (p<0.05) breastfed[12]. It shows that extended breastfeeding may prove advantageous in preventing chronic malnourishment more than the acute one because mother’s milk always remains a good source of vital nutrients which supplements the child health in a big way. Even vegetarians were found to be 2.18 times more wasted (p<0.01) as compared to ovo- and non-vegetarians which indicates that small amount of high biological value protein foods may have long term benefits in child’s growth and development. A hypothesis of relating a nuclear family with having a better nutritional status was investigated, but unlike some studies [13] it did not have significant association with the prevalence of underweight and wasting but on the contrary, children living in joint family were found to be more at risk of being chronically malnourished. In fact, it is the size of a family which has been found to be inversely related to appropriate weightfor- age and weight-for-height of the child. Family size of more than 12 members had worse weight-for- age (p<0.001) and weight-for-height (p<0.001) status as compared to that of 9-12 members. Rural settlements were found to have been highly associative with the incidence of underweight and wasting against that of urban areas [14]. On examining the socio-economic attributes of the population (Table:2), it was learned that the educational status of both mother and father had an adverse affects on the health of their wards. With graduation as a reference category it was found that mother who were illiterate (p<0.01) and mother who had the secondary level of education (p<0.05) had children who weighed below average and similar was the case with wasted children [10]. Like some studies, this study establishes a stronger association of the father’s education with their child’s nutritional status (compared to that of the mothers), as those who did not receive schooling (p<0.01), received only secondary level (p<0.01) and high school (p<0.05) had 2.12, 2.25 and 1.91 times more chances of parenting an underweight child. It signifies that above the financial aspect the authoritative management of an educated father could be a point in mitigating the health problems in conservative and backward communities. Occupation is a function of one’s educational status and so most of the underweight and thin children belonged to the fathers who were peasants or laborers (p<0.05), however in other classes the association was not found to be as significant [15]. Per capita income has been defined as a better parameter for assessing the socio-economic status of the household as it takes into account the size of the family. Thus, it was seen that children of the family having the lowest Per capita income of 100- 500 rupees were most undernourished (p<0.001) and wasted (p<0.001) [16].

CONCLUSION

This study concludes that amongst all the other factors variables like parent’s education, per capita income, family size and type of settlement are highly associated with the prevalence of malnutrition in the children. Thus, there needs to be an implementation of a comprehensive malnutrition combating strategy which not only takes care of the nutrition intervention or supplementation but also education and social alleviation.

Funding agencies: Authors are grateful to University Grants Commission (UGC) for the funding of this study under the UGC-JRF (University Grants Commission – Junior Research Fellowship) scheme

Conflict of interests: The authors have no conflict of interests

Contributors: R, SM and PT collected the data.US: collected the data and conducted the study; NY: conceived and supervised the study; US and NY finalized the manuscript and will be guarantors’.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to the director Prof. G. K Rai and the authorities of the Centre of Food Technology, for providing the basic necessities and support without which this study would not have been possible. We acknowledge the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. The authors are also grateful to authors / editors /publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed throughout this study. Authors are grateful to IJCRR editorial board members and IJCRR team of reviewers who have helped to bring quality to this manuscript.

References:

1. Sachdev HPS. Assessing child malnutrition - some basic issues. Bull Nutr Foundations India 1995; 16 : 1-5.

2. UNICEF. The state of the world’s children. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998.

3. (No authors listed). Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser.1995; 854:1-452.

4. Sachdeva S, Alam S, Beig FK, Khan Z, Khalique N. Determinants of vitamin A deficiency amongst children in Aligarh district, Uttar Pradesh. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:861-66.

5. Kapil U, Toteja GS, Rao S, Pandey RM. Zinc Deficiency amongst Adolescents in Delhi. Indian Pediatr.2011; 48:981- 981.

6. Kumar R, Singh J, Joshi K, Singh HP, Bijesh S. Co-morbidities In Hospitalized Children with Severe Acute Malnutrition. Indian Pediatr. 2014; 51:125-127.

7. Gibson RS. Principles of Nutritional Assessment, 2nd ed. 2005. Oxford University Press. London.

8. Group WW. Use and interpretation of anthropometric indicators of nutritional status. Bull WHO. 1986;64:929–41.

9. WHO, WHO Multicenter Growth Reference Study, Measurement and Standardization protocol. , 1998. WHO, limited circulation –WHO/Geneva.

10. Victoria CG. The association between wasting and stunting: an international perspective. J Nutr. 1992; 122:1105- 1110.

11. Joshi HS, Joshi MC, Singh A, Joshi P, Khan NI. Determinants of protein energy malnutrition (pem) in 0-6 years children in rural community of Bareilly. Indian J. Prev. Soc. Med. 2011; Vol. 42 No.2.

12. Cousens S, Nacro B, Curtis V, Kanki B, Tall F, Traore E, Diallo I, Mertens T. Prolonged breast-feeding: no association with increased risk of clinical malnutrition in young children in Burkina Faso. Bulletin World Health Organization.1993; 71(6):713–72.

13. Singh AK, jain S, Bhatnagar M, Singh JV, Garg SL, Chopra H. Socio-demographic determinants of malnutrition among children of 1-6 years of age in rural Meerut . Indian J. Prev. Soc. Med. 2012; Vol. 43:3.

14. Jeyaseelan L , Lakshman M. Risk factors for Malnutrition in south Indian children. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2001; 29: 93-100

15. Basit A, Nair S, Chakraborthy KB, Darshan BB, Kamath A. Risk factors for Under-nutrition among children aged one to five years in Udupi taluk of Karnataka, India: A case control study. Australasian Medical Journal.2012; Vol. 5(3): 163-167.

16. Victora, C. Risk factors for malnutrition in Brazilian children: the role of social and environmental variables. Bulletin World Health Organization. 1986; 64: 299-309.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License