IJCRR - 7(2), January, 2015

Pages: 21-40

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

AGE AND GENDER RELATED CHANGES IN MIDSAGITTAL DIMENSIONS OF THE LUMBAR SPINE IN NORMAL EGYPTIANS: MRI STUDY

Author: Fathy Ahmed Fetouh

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Background: Degeneration of lumbar spine is a common and age related finding in the normal population. Eighty percent of adult population suffer from at least one episode of low back pain during their life time. Objective: The present work aimed to study the midsagittal dimensions of lumbar vertebrae, intervertebral discs, and vertebral canal in normal Egyptian population in different age groups in both males and females using MRI. Materials and methods: A retrospective study of MRI midsagittal images of lumbar spine was carried out for normal Egyptian population whose ages ranged from 20 to 60 years old and divided into 4 age groups (decades). The parameters measured for the discs were; anterior, central, posterior disc heights, relative disc height index and anteroposterior disc diameter, while the parameters measured for the vertebrae were; central height, anteroposterior diameter, midsagittal canal diameter and canal/ body ratio. The data were statistically analyzed and tested for significance between age groups and between males and females. Results: The measured parameters of the discs increased with age progress with significant differences at different levels between age groups. Also, they were found to be greater in males than females with significant differences. The relative disc height index showed a constant relationship between males and females. For the vertebrae, the parameters showed no significant differences related to age progress, while they were greater in males than females at all levels in all age groups. The midsagittal canal diameter and canal/body ratio indicated that the canal diameter decreased steadily from 3rd to 6th decade and was more capacious in females than in males. Conclusion: The measurements obtained in the present study can be considered as a database which can be helpful to clinicians, therapists, and researchers as ready references of lumbar spine in normal adult Egyptian population. Any deviation from these values should be correlated with clinical findings.

Keywords: Aging, Sexual dimorphism, Lumbar intervertebral disc, Midsagittal canal diameter, MRI

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

The lumbar spine has a larger mobile segment in the sagittal plane.1 Changes in the aging spine usually occur at movable intervertebral discs, facet joints, ligamentum flavum, and vertebral endplate which are adjacent to the intervertebral discs.2-4 The intervertebral discs undergo an age-related process of degeneration as early as 2nd decade, which is manifested by gradual structural transition of disc components.5 The central region of the vertebrae adjacent to nucleus pulposus is exposed to greater vertical stress than other regions.6 Among the various problems with spinal aging, lumbar spinal stenosis is the most frequent indication for spinal surgery in people over 60 years old.7 Also, pathological changes can occur in diameter of the lumbar spinal canal, therefore assessing the canal size is considered as an important diagnostic procedures.8 The sagittal anteroposterior diameter of the spinal canal is the only parameter which could be statistically correlated with the cross sectional area and it is accepted to use it as an indicator of the size of spinal canal.9 Since the magnification errors resulting from non-standardized film-tube distance is possible in the studies using the plain films, the magnetic resonance imaging is a more reliable in measurements of the intervertebral discs.10 The quantitative studies concerning the lumbar spine in Egyptians are to our knowledge still scarce. The present work aimed to study the midsagittal dimensions of lumbar vertebrae, intervertebral discs, and vertebral canal in normal Egyptian population in different age groups in both males and females using MRI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

A retrospective study of MRI midsagittal images of lumbar spine was done for cases referred to ELnour Radiology Center in Sharkia Governorate, Egypt in the period between August 2013 and September 2014. Patients consent was not required for the retrospective review of records and images because patient anonymity was preserved.The criteria for selection included the images which were obtained for various reason such as; abdominopelvic problems, muscle pain, and soft tissue injuries. MRI showing evidences of fracture, congenital anomalies, degenerative changes, endplate sclerosis, spinal metastasis or any other pathologies were excluded according to reading of radiologist. The data about age and sex were recorded. The selected cases were 104 in number (52 males and 52 females). In order to avoid uncertainty of measurements caused by secondary ossification centres of vertebrae before 20 years and osteoporosis after 60 years, subjects between 20 to 60 years were selected and divided into 4 age groups (decades): 3rd decade (20- 29 years), 4th decade (30 - 39 years,) 5th decade (40 - 49 years), and 6th decade (50-59 years).

Technique

The lumbar spine was examined with the use of GE Signa Pofile 0.2T Open MRI Scanner. T2-weighted images with sagittal plane were obtained with a repetition time (TR) of 2600 milliseconds and echo time (TE) of 100 milliseconds. Slice thickness was 4 mm. The field of view (FOV) used was 25-30 cm. Distances and diameters were measured in millimetres using the software that accompanies the MRI system.

Measurements

Measurements were done at the midsagittal T2-weighted images which were identified when the tips of the spine processes were seen. The landmarks for measurements were taken at extreme anterior or posterior margins of the endplates of vertebrae.11 The following dimensions were measured for intervertebral discs: 1-Anterior disc height: was measured as the distance between the extreme anterior margins of the two adjacent vertebral endplates (Fig. 1A) 2-Central disc height: was measured as the distance between the midpoints of the two adjacent vertebral endplates (Fig. 1B) 3-Posterior disc height: was measured as the distance between the extreme posterior margins of the two adjacent vertebral endplates (Fig. 1A) 4-Anteroposterior disc diameter: was measured as the distance between the midpoints of the anterior and posterior disc heights (Fig.1C) 5-Relative disc height index= mean of central disc height/mean of central vertebral height.3,11-15 For the lumbar vertebrae, the following dimensions were measured: 1-Central vertebral height: was measured as the distance between the midpoints of the superior and inferior endplates of each vertebra (Fig.1D) 2-Anteroposterior diameter of vertebral body: was measured as the greatest mid waist distance between midpoints of anterior and posterior borders of the vertebral bodies (Fig.1E) 3-Midsagittal canal diameter: was measured from midpoint of the posterior border of vertebral body to the most anterior part of spinous process. ( Fig.1F) 4-Canal/body ratio= midsagittal canal diameter/anteroposterior diameter of the vertebra.10,16-22 All the measurements were taken 2 times and the mean was assessed to minimize the intra-observer error.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS for windows software program. Descriptive statistical analysis for all the data were presented as mean and standard deviation. Paired sample t-test was used to evaluate the differences between male and female measurements and between successive age groups. The differences were considered significant when P value <0.05.

RESULTS

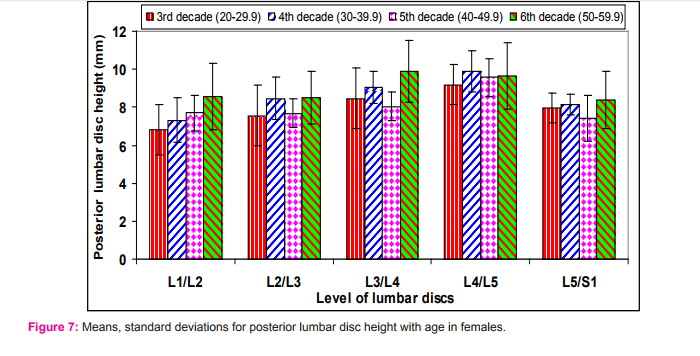

The means of anterior lumbar disc heights for males and females in different age groups are shown in table (1) and figures (2&3). The discs at levels of L1/L2, L4/ L5& L5/S1 showed significant changes with age progress which were more striking in females than males. The males differed from females in the response of anterior disc height to age progress. At the upper 4 discs, the male discs showed alternating increase/decrease pattern through the age decades from 3rd-6th, while in females there was steady increase in the height to reach the maximum at 6th decade. At L5/S1 disc, both males and females showed steady increase from 3rd to 6th decade. Taking the 3rd decade as a reference, the discs have gained an increase in anterior height by 6th decade which was significant mainly in females (p<0.05). Also, there was a cephalocaudal gradient of increase from L1/L2 to L5/S1 discs nearly in all decades studied except L5/S1. disc in 3rd and 4th decades at which it decreased. The values were greater in males than females in all decades (3rd- 6th) and the differences were significant mainly in 3rd-5th decades. The means of central lumbar disc heights for males and females in different age groups are shown in table (2) and figures (4&5). All discs showed significant changes in their central heights with age. The males differed from females in the response of central disc height to age progress. In males, there was an alternating increase/decrease pattern at most of the disc levels, while in females there was steady increase to reach the maximum in 6th decade at most of the disc levels. Taking the 3rd decade as a reference, the discs have gained an increase in the central height by 6th decade which was significant at most of the segmental levels for both males and females (p0.05). The means of anteroposterior diameter of lumbar discs for males and females in different age groups are shown in table (4) and figures (8&9). The discs at the upper levels (L1/L2, L2/L3& L3/L4) showed significant changes with age between 5th- 6th decade only in females. The males differed from females in the response of anteroposterior diameters of the discs to age progress. In males, there was steady increase from the 3rd to 6th decade, while in females there was none linear alternating increase/decrease pattern. Taking the 3rd decade as a reference, the discs have gained an increase in the anteroposterior diameter by 6th decade which was significant at the level of L2/L3, L3/L4 & L5/S1 discs especially in females. There was a cephalocaudal gradient of increase from L1/L2 to L4/L5 discs followed by a decrease in L5/ S1 disc in both males and females in all age groups. The values were greater in males than females and the differences were significant at all segmental levels nearly in all decades (p<0.05). The means of relative disc height indices for males and females in different age groups are shown in table (5) and figures (10&11). No significant differences were observed between males and females, so a constant relationship was observed at all levels, between height of the vertebral body and thickness of the disc in both males and females. Taking the 3rd decade as a reference, the discs have gained an increase in the relative disc height index by the 6th decade which was significant at all levels (p<0.05). The means of central heights of lumbar vertebrae for males and females in different age groups are shown in table (6) and figures (12&13). No significant differences were observed between successive age groups at all levels for both males and females. No gained increase of the height in 6th decade when compared to 3rd decade. Also, no craniocaudal gradient of increase was observed between segmental levels. On the other hand, the mean values of central heights were greater in males than females with significant differences at all levels in all age groups studied (p<0.05). The means of anteroposterior diameters of lumbar vertebrae for males and females in different age groups are shown in table (7) and figures (14&15). No significant changes were observed between successive age groups at all levels for both sexes. There was only significant gradient of increase in 6th decade when compared to 3rd decade at L1, L4, L5. A cephalocaudal gradient of increase was observed from L1 to L3 and then became constant at L4 and L5. The values were greater in males than females with significant differences at all levels and nearly in all age groups (p<0.05). The means of midsagittal canal diameters of lumbar vertebrae for males and females in different age groups are shown in table (8) and figures (16&17). They decreased steadily from 3rd - 6th decade at all levels in both males and females and the differences were significant only in certain age groups at certain levels. Also, they declined in 6th decade when compared to 3rd decade and the differences were significant at most of the levels. As regards to cephalocaudal sequence, generally there was slightly steady decrease from L1 - L4 followed by steady increase at L5 in 3rd and 4th decades and general steady decrease from L1- L5 in 5th and 6th decades. The diameters were slightly wider in females than in males with significant differences at certain levels in 4th and 5th decades. The canal/body ratio are shown in table (9) and figures (18&19). The ratio decreased steadily as age progress from 3rd- 6th decade in both males and females at all levels. The canal/body ratio declined at 6th decade when compared to 3rd decade with significant differences at all segmental levels. There was cephalocaudal gradient of decrease in canal/body ratio from L1- L4 then increased at L5 in 3rd and 4th decades and general steady decrease from L1- L5 in 5th and 6th decades. The ratio was higher in females than in males with significant differences in all age groups at all levels (p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the males differed from females in the response of their lumbar disc heights to age progress. In males, there was alternating pattern of increase/decrease, while in females there was steady increase. This is in accordance with Al-Hadidi et al. 13 who found that the midpoint height displayed an alternating pattern which was of higher magnitude and statistically significant in males, but less evident and statistically insignificant in females. The alternating increase/decrease pattern seems to reflect periods of growth and remodelling in relation to changes of functional demands.12,23 In the present study, there were significant differences in disc heights and diameter with age progress, Which were more striking in females than in males. This is in accordance with Amonoo-Kuofi 12 who found that the heights and diameters of intervertebral discs vary significantly in different age groups. On the other hand, Aydinlioglu et al. 11 found that the changes related to disc heights in females did not reach to the level of significance and the height of intervertebral discs increases with aging only in males. The disc heights in the present study, appeared to have gained an increase in 6th decade when compared to 3rd decade with significant differences in both males and females at different segmental levels. This is in agreement with many authors who found that the heights of intervertebral discs increase in older age groups in both males and females and these discs sink into the vertebrae.13,17,24 The aging of the disc involves structural changes in the endplate and between the age of 20 and 65 years, the endplate becomes thinner and cell death occurs in the superficial layer of the cartilage.25 Aging causes inevitable and progressive changes in disc matrix composition, which resemble changes in other aging cartilaginous tissues.26,27 Biochemical changes occur as a direct result of the alternation with age lead to deterioration of connective tissues and loss of disc integrity.28 In the present study, a cephalocaudal gradient of increase was observed in the lumbar disc heights and diameters from the level of L1/L2 to L4/L5 discs followed by a decline at lumbosacral disc (L5/S1) especially in 5th and 6th decades. This is in accordance with Eijkelkamp et al. 29 and Moeller and Reif 30 who reported that the heights of intervertebral discs increase from L1/L2 to L4/ L5 discs then decreases at L5/S1 disc. Also, Bogduk et al. 31 reported that the L4/L5 disc is the largest intervertebral disc of human body and this is probably related to the greater mobility at that level of lumbar spine. On the other hand, Shao et al. 14 and Gocmen-Mas et al. 15 found that the intervertebral disc height increased with increasing level from L1/L2 to L5/S1 discs in both males and females. Shukri et al. 32 found that the height of L5/ S1 disc was quite variable: in some subjects it was small, however in others it was the largest one. In the present study, the mean values of disc heights were greater in males than females with significant differences. This is in consonance with Amonoo-Kuofi 12, Frobin et al. 24 and Shukri et al. 32 who found that the mean disc height was larger in male than female subjects at all level except at L5/S1 disc at which, the disc height was slightly larger in females. In the present study, there was a constant relationship in the relative disc height index between males and females at all levels in all age groups. This is in accordance with the authors who found that in absence of degeneration, the relative disc height index has been shown to be constant in males and females at all disc levels. This reflects a coordinated change affecting discs and vertebrae simultaneously.12,13 Based on this, the relative disc height index could prove helpful as an indicator for pathological conditions affecting the spine. Significant aberration of this index could be interpreted as a sign of disc degeneration in terms of altered coordination of disc and vertebral height.13 The central height and anteroposterior diameter of lumbar vertebrae in the present study showed no significant changes with age progress. This disagrees with Masharawi et al. 33 who found that bony lumbar vertebrae change significantly usually decreasing in height and broadening. Sone et al. 34 related changes in vertebral height to the osteoporosis and Goh et al. 35 related these changes to the biomechanical load acting on spine. The absence of changes in height and anteroposterior diameter of the vertebrae in present study may indicate that the osteoporosis and biomechanic load have not affected the subjects of the study. In the present study, these values were greater in males than females with significant differences at all levels in all age groups. This is in agreement with Amonoo-Kuofi 12 and Shukri et al. 32 who found that the dimensions of lumbar vertebral bodies were larger in males than females at all levels. On the other hand Frobin et al. 36 reported that the height of lumbar vertebral body is larger in females than males and Gilsanz et al. 37 found that there is no sexual dimorphism in measurements of lumbar vertebral bodies. A cephalocaudal gradient of increase was observed in the anteroposterior diameter from L1- L3 and became constant at L4 and L5. This is in agreement with Standring et al. 38 who reported that there is a cephalocaudal increase in width of the vertebral bodies to 3rd lumbar. Shukri et al. 32 found that the width of vertebral bodies have increased from L1- L4 then decreased at L5 level. This can be explained by that L4 and L5 have the largest flexion extension movements, so L4 and L5 are the most common sites for degenerative spine disease.39,40 In the present study, the midsagittal canal diameter decreased steadily with age progress from 3rd- 6th decade at all levels in both males and females. The values in 6th decade were significantly decreased when compared to 3rd decade. This is in general consonance with many authors who found that the bony lumbar spinal canal and foramina shrink with aging 17 and spinal stenosis syndrome affects mainly patients in their 5th- 6th decade of life.19 Narrowing of the spinal canal may be developmental or it may be a result of degenerative changes from aging.21 On the other hand, this disagrees with Kim et al. 22 and Ericksen 41 who reported that age is not associated with spinal canal width and length variations in thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in normal people. A cephalocaudal gradient of decrease was observed from L1-L4 in 3rd and 4th decades and from L1-L5 in 5th and 6th decades. This is in consonance with many authors who observed a gradual decrease in sagittal canal diameter of the spinal canal from L1-L5.42-44 Previous studies measured the midsagittal canal diameter in normal Egyptian population using different methods. In postmortal lumbar vertebrae of Egyptian, the midsagittal canal diameter decreased from L1- L3 and then increased again until L5.45 Also, in dry bones, the mean anteroposterior diameter increased from L1 to L3.46 By radiological study with plain x rays, the mean anteroposterior canal diameter in both males and females showed an initial increase from L1 to L2 then decreased gradually at L5.46 By computed tomography scans, the midsagittal canal diameter from L1-L5 had an hourglass shape, where the narrowest diameter was at L3.47 These differences can be explained due to differences in the methods used for measurements with magnification errors in the studies using plain films and postmortal changes in the studies using dry bones. The current measurements were performed on living humans using MRI which was found to be the best imaging modality.32 In the present study, the mean midsagittal canal diameter was slightly wider in females than in males and the differences were significant at certain levels in 4th and 5th decades. This is in accordance with Eisenstein 48 in south African population, Malas et al. 49 in Turkish and Adam 50 in Sudanese who found that the females have wider vertebral canal than males. On the other hand, some authors found that the mean midsagittal diameter of lumbar bony spinal canal was narrower in females than males.16,21,32 Janjua and Muhammad 42 found that the lumbar spinal canal showed a constant dimensions in both males and females by x ray. The canal/ body ratio is more reliable than the vertebral canal diameter in detecting the degree of stenosis.51 The ratio in the present study was greater in females than males with significant differences at all levels in all age groups studied. The ratio decreased steadily from 3rd to 6th decade. This indicated that the midsagittal canal diameter was more capacious in females than males and in younger age than in older age groups. This is in agreement with Janjua and Muhammad 42 who found that the female midsagittal canal diameter is relatively wider than that of males and the differences between the mean values of canal/body ratio were significant at the level from L1 to L4, while at L5 the differences were not significant.

CONCLUSION

It could be concluded that the measurement obtained in the present study can be considered as a database which can be helpful to clinicians, therapists, and researchers as ready references of lumbar spine in normal adult Egyptian population. Any deviation from these values should be correlated with clinical findings. Further studies are needed with a larger sample in order to support our data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to express his cordial gratitude to Dr Abdelgied Ahmed Fetouh specialist of radiodiagnosis and all who work in Elnour Radiology Center for their cooperation and facilitation to obtain the studied MR images. Also the Author acknowledges the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. The author is grateful to authors / editors / publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed. Source of funding: None Conflict of interest: None declared.

References:

1. Takeda N, Kobayashi T, Atsuta Y, Matsuno T, Shirado O, Minami A. Changes in the sagittal spinal alignment of the elderly without vertebral fractures: a minimum 10-year longitudinal study. J Orthop Sci 2009; 14(6):748 -753.

2. Twomey L, Taylor J. Age changes in the lumbar spinal and intervertebral canals. Paraplegia 1988;26:238-249.

3. Shao Z, Rompe G, Schiltenwolf M. Radiographic changes in the lumbar intervertebral discs and lumbar vertebrae with age. Spine 2002; 27; 263-268.

4. Vernon-Roberts B, Moore RJ, Fraser RD. The natural history of age-related disc degeneration: the influence of age and pathology on cell populations in the L4-L5 disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:2767-2773.

5. Naylor A. The biophysical and biochemical aspects of intervertebral disc herniation and degeneration. Ann R Coll Surg 1962; 31: 91-114.

6. Ferguson SJ, Steffen T. Biomechanics of the aging spine. Eur Spine J 2003; 2: S97-S103.

7. Abbas J, Hamoud K, May H, Hay O, Medlej B, Masharawi Y, et al. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis and lumbar spine configuration. Eur Spine J 2010;19:1865-73.

8. Santiago FR, Milena GL, Herrera RO, Romero PA, Plazas PG. Morphometry of the lower lumbar vertebrae in patients with and without low back pain. Eur Spine J 2001; 10(3):228-233.

9. Gepstein R, Folman Y, Sagiv P, Ben David Y, Hallel T. Does the anteroposterior diameter of the bony spinal canal reflect its size? An anatomical study. Surg Radiol Anat 1991;13:289-291.

10. Sevinc O, Barut C, Is M, Eryoruk N, Safak A. Influence of age and sex on lumbar vertebral morphometry determined using sagittal magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Anat 2008; 190:277-83.

11. Aydinlioglu A, Diyarbakirli S, Keles P. Heights of the lumbar intervertebral discs related to age in Turkish individuals. Tohoku J Exp Med 1999; 188: 11-22.

12. Amonoo-Kuofi HS. Morphometric changes in the heights and anteroposterior diameters of the lumbar intervertebral discs with age. J Anat 1991; 175: 159-168.

13. Al-Hadidi MT, Badran DH, Al-Hadidi AM, Abu-Ghaida JH. Magnetic resonance imaging of normal lumbar intervertebral discs. Neurosciences 2001; 6 (4): 227-232.

14. Shao Z, Rompe G, Schiltenwolf M. Radiographic changes in the lumbar intervertebral discs and lumbar vertebrae with age. Spine 2004; 29:108-9.

15. Gocmen-Mas N, Karabekir H, Ertekin T, Edizer M, Canan Y Izzet duyar I. Evaluation of lumbar vertebral body and disc: a stereological morphometric study. Int J Morphol 2010;28 (3):841-847.

16. Amonoo-Kuofi HS. The sagittal diameter of the lumbar vertebral canal in normal adult Nigerians. J Anat 1985; 140 (1): 69-78.

17. Twomey LT, Taylor JR. Age changes in lumbar vertebrae and intervertebral discs. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987; 224:97-104.

18. Lee HM, Kim NH, Kim HJ, Chung IH. Morphometric study of the lumbar spinal canal in the Korean population. Spine 1995 (Phila Pa 1976) 20:1679-1684.

19. Tacar O, Demirant A, Nas K, Altinda? O. Morphology of the lumbar spinal canal in normal adult Turks. Yonsei Med J 2003; 44(4):679-685

20. Jahangir M, Dar S, Jeelani G. Antero-posterior measurement of the lumbar spinal canal on mid sagittal MRI in Kashmiri adults. JK-Practitioner.2003; 10(4): 284-285.

21. Al-Anazi A, Munir N, Khaled M, Hosam A. Radiographic measurement of lumbar spinal canal size and canal/body ratio in normal adult Saudis. Neurosurgery Quarterly 2007; 17 (1):19-22.

22. Kim KH, Park JY, Kuh SU, Chin DK, Kim KS, Cho YE. Changes in spinal canal diameter and vertebral body height with age. Yonsei Med J 2013;54 (6):1498-1504.

23. Oda J, Tanaka H, Tsuzuki N. Intervertebral disc changes with aging of human cervical vertebra from neonate to the eighties. Spine 1988; 13: 1205-1211.

24. Frobin W, Brinckmann P, Biggemann M, Tillotson M, Burton K. Precision measurement of disc height, vertebral height and sagittal plane displacement from lateral radiographic views of the lumbar spine. Clin Biomech 1997; 12(1):51- 63.

25. Bernick S, Cailliet R. Vertebral end-plate changes with aging of human vertebrae. Spine 1982;7:97–102.

26. Anderson DG, Li X, Tannoury T, Beck G, Balian G. A fibronectin fragment stimulates intervertebral disc degeneration in vivo. Spine 2003;28:2338–45.

27. Buckwalter JA. Aging and degeneration of the human intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20 (11):1307- 14.

28. Pokharna HK, Phillips FM. Collagen cross-links in human lumbar intervertebral disc aging. Spine 1998;23:1645- 1648.

29. Eijkelkamp MF, Klein JP, Veldhuizen AG, Van Hom JR, Verkerke GJ. The geometry and shape of the human intervertebral disc. The International Journal of Artificial Organs. 2001; 24: 75-83.

30. Moeller TB, Reif E. Normal Findings in CT and MRI. First edition, Thieme, Stuttgart, Germany. 2000: 82 & 174.

31. Bogduk N, Tynan W, Wilson AS. The nerve supply to the human lumbar intervertebral discs. J Anat 1981; 132: 39-56

32. Shukri IG, Mahmood KA, Abdulrahman SA. a morphometric study of the lumbar spine in a symptomatic subjects in Sulaimani city by magnetic resonance imaging. JSMC, 2013; 3(1):21-31.

33. Masharawi Y, Salame K, Mirovsky Y, Peleg S, Dar G, Steinberg N, et al. Vertebral body shape variation in the thoracic and lumbar spine: characterization of its asymmetry and wedging. Clin Anat 2008;21:46-54.

34. Sone T, Tomomitsu T, Miyake M, Takeda N, Fukunaga M. Age-related changes in vertebral height ratios and vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 1997; 7:113-118.

35. Goh S, Tan C, Price RI, Edmondston J, Song S, Davis S, Singer KP. Influence of age and gender on thoracic vertebral body shape and disc degeneration: an MR investigation of 169 cases. J Anat 2000; 197: 647-657.

36. Frobin W, Brinckmann P, Biggemann M, Tillotson M, Burton K. Precision measurement of disc height, vertebral height and sagittal plane displacement from lateral radiographic views of the lumbar spine. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1997;12(suppl 1):51- 64.

37. Gilsanz V, Boechat MI, Gilsanz R, Loro ML, Roe TF, Goodman WG. Gender differences in vertebral sizes in adults: biomechanical implications. Radiology 1994;190: 678-682.

38. Standring S, Ellis H, Healy JC, Johnson D, Williams A, Collins P et al. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. Thirty-ninth edition, Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh; 2005: 735-756 & 789-793.

39. Panjabi MM, White AA. 3rd Basic biomechanics of the spine. Neurosurgery 1980;7:76-93.

40. Panjabi MM, Goel V, Oxland T, Takata K, Duranceau J, Krag M, et al. Human lumbar vertebrae. Quantitative three-dimensional anatomy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992;17:299- 306.

41. Ericksen MF. Some aspects of aging in the lumbar spine. Am J Phys Anthropol 1976;45(3 pt. 2):575-580.

42. Janjua MZ, Muhammad F. Measurements of the normal adult lumbar spinal canal. J Pak Med Assoc 1989; 39(10):264-8

43. Wang TM, Shih C. Morphometric variations of the lumbar vertebrae between Chinese and Indian adults. Acta Anatomica 1992; 144: 23-29.

44. Rema D, Rajagopalan N. Dimensions of the lumbar vertebral canal. Indian J Orthop 2003; 37(3): 44-46.

45. AkI M, Zidan A. Morphometry of the lumbar spine and lumbosacral region in Egyptians. Egypt Orthop J 1983; 18:34–43.

46. El-Rakhawy M, El-Shahat A, Labib I, Abdulaziz E. Lumbar vertebral canal stenosis: concept of morphometric and radiometric study of the human lumbar vertebral canal. Anatomy 2010; 4: 51-62.

47. Aly T, Amin O. Geometrical dimensions and morphological study of the lumbar spinal canal in the normal Egyptian population. Orthopedics 2013;36(2):e229-34.

48. Eisenstein S. The morphometry and pathological anatomy of the lumbar spine in South African Negroes and Caucasoids with specific reference to spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1977; 59 B:173-180.

49. Malas MA, Salbacak A, Aler A, Yardimci C. Mid sagittal diameters of the lumbar vertebral canal determined by magnetic resonance imaging. SDÜ Tip Fakültesi Dergisi. 1997; 4(3): 7-11.

50. Adam, RAA. Measurement of lumbar canal diameter in Sudanese population using computerize tomography scanning. Sudan University of Science and Technology, Medical Radiologic Science 2011, M.Sc. Thesis.

51. Gupta M, Bharihoke V, Bhargava S.K. Agrawal N. Size of the Vertebral Canal—A correlative study of measurements in radiographs and dried bones. J Anat Soc India 1998;47: 1-6.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License