IJCRR - 13(22), November, 2021

Pages: 30-34

Date of Publication: 20-Nov-2021

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

Clinical Profile, Ocular Morbidity and Visual Loss in Psoriasis

Author: Deb D, Annamalai R, S. Anandan, S. Murugan, M. Muthayya

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Aim: To study the clinical profile of ocular psoriasis and to identify features that help in the recognition and prevention of ocular morbidity and visual loss in these patients. Methods: A prospective observational study was conducted on 100 patients with psoriasis in a tertiary care, multispecialty hospital. All patients underwent systemic evaluation by the dermatologist, followed by ophthalmic evaluation comprising of visual assessment, slit lamp examination, ophthalmoscopy, Schirmer's test, tear breakup time, Rose Bengal staining and ancillary investigations such as fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) and optical coherence tomography (OCT). Results: Among 100 patients with psoriasis, the prevalence of ophthalmic manifestation was 60%, of whom 42% were symptomatic. Ocular features were most common in scalp psoriasis and pustular psoriasis. The type and severity of ocular manifestation had a positive correlation with the duration of psoriasis. The most common ophthalmic feature was keratoconjunctivitis sicca (55%), followed by meibomitis (50%), cataract (35%), blepharitis (20%) and uveitis (5%). Uveitis had associated with psoriatic arthritis. The correlation was established using the kappa coefficient. Statistical significance was found in the conjunctival staining pattern with a p-value = 0.02. Steroid-induced glaucoma occurred in 24%. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and corticosteroids used in the management of systemic psoriasis were found to be the most frequent causes of visual morbidity. Conclusion: Ophthalmic clinical features, signs and symptoms in psoriasis may be subtle and a complete ophthalmic evaluation is required both for early detection of ocular abnormalities and complications. A multidisciplinary approach is required to reduce ocular morbidity in the active phase of psoriasis during and after treatment in these patients.

Keywords: Cataract, Corticosteroids, Keratoconjunctivitis sicca, Psoriasis, Uveitis, Visual morbidity

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is an autoimmune, chronic, painful, and disabling disease that affects the quality of life of the patient.1 It is an immune-mediated condition where TH1 produces pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-12, which underlies the disease process. The prevalence of psoriasis worldwide varies between 0.09%- 11.4%.2,3 The prevalence of psoriasis in India is estimated at around 0.7%.4 The lesions seen typically in psoriasis have a well-demarcated plaque, erythematous base, and silvery scales on the surface of the lesion. These lesions are mostly seen on extensor surfaces and as scalp lesions. The most common type is psoriasis Vulgaris. The other types of psoriasis include guttate, erythrodermic, pustular, and inverse psoriasis.5

Psoriasis is known to be associated with multiple systemic conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and stroke.

Ocular manifestations are seen in about 10% of cases with psoriasis,6,7 more so with the pustular psoriatic type. Ocular manifestations of psoriasis may be either direct involvement or immune-mediated. The various known ocular manifestations associated with psoriasis are blepharitis, ectropion, trichiasis, conjunctivitis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, corneal melting, episcleritis, cataract, ocular hypertension, uveitis, and macular oedema.

Uveitis is seen more commonly in patients with psoriatic arthritis than psoriasis alone and the articular features precede the ocular manifestations. The severity of ocular inflammation correlates more with skin disease than the extent of joint involvement in psoriasis.8 The severity of psoriasis has a positive correlation with anterior uveitis. It has been postulated that patients with HLA B27 and psoriasis, present with a severe form of uveitis. Uveitis in turn may lead to retinal vascular occlusions, secondary glaucoma, inflammatory optic neuropathy, and retinal detachment, which results in temporary or permanent loss of vision.

This study aimed to identify the prevalence and analyze the various ocular morbidities and their association with the type of psoriasis. Since most of the patients with psoriasis present late to an ophthalmologist either due to lack of awareness or fewer symptoms, it is of utmost importance that the dermatologist and ophthalmologist evaluate a patient with psoriasis completely and in collaboration before they develop sight-threatening morbidities.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This is a prospective, observational, descriptive study on 100 patients with psoriasis visiting a tertiary care centre in Chennai, South India. The hospital has a well-equipped psoriasis clinic and an Ophthalmology department. The study was conducted over 1 year from January 2020 to December 2020, after obtaining Institutional ethics approval (CSP-MED/18/OCT/47/171). The patients were followed up every 3 weeks and more frequently whenever required.

All psoriasis patients were referred to the Ophthalmology department for a complete ophthalmic evaluation. Psoriasis patients were diagnosed clinically and severity was rated using Psoriasis Area and Severity Index and the Dermatological Life Quality Index.9 We excluded severely ill patients, patients who had known ocular morbidities associated with other systemic conditions. Informed consent was obtained from each patient before enrolling them in this study. We noted down the demographic details of patients visiting us with psoriasis, along with the type of psoriasis, duration of the condition, treatment for the disease, and any family history of similar condition. The ophthalmic evaluation consisted of the assessment of extraocular movements, best-corrected visual acuity for distance and near vision, refraction, colour vision testing, slit lamp examination, ophthalmoscopy, and intraocular pressure assessment by Goldmann’s applanation tonometer. They were evaluated for dry eye by measuring the tear meniscus height, Schirmer’s test, tear break-up time, and Rose Bengal conjunctival staining. Van Bijsterveld scoring system was used to assess dry eye where the cornea is divided into three zones and graded in each zone and subsequently counted to give the total score.

The data collected were analyzed to calculate the prevalence of various ocular manifestations in psoriatic patients. During the follow-up visit, the patients were also reviewed by the dermatologist to assess improvement in the systemic illness.

Statistical analysis: All the data was collected and analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics software, Version 23.0. In descriptive statistics, frequency analysis for data distribution and percentage analysis was done for categorical variables. Mean and standard deviation was analyzed using continuous variables. Kappa coefficient was used for the correlation of test values. Statistical significance in categorical data was done using the Chi-Square test. A probability value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A prospective, observational, cohort study was performed on 100 patients with an established diagnosis of psoriasis. In our study, among 100 patients, ophthalmic manifestations were noted in 60 patients (60%). Males were affected in 27% and females in 71%. The age group affected was most frequently between 40-65 years (median age 47 years). Bilateral involvement occurred in 88% of patients and was statistically significant with p=0.01. The most common symptom was irritation or burning and foreign body sensation in both eyes.

The most common type of systemic psoriasis in our patients was psoriasis Vulgaris(54%). Ocular features were seen more commonly in patients with psoriasis Vulgaris (41.6%) (Table 1). Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ocular surface disease were more common in patients with scalp psoriasis (41%) and pustular psoriasis (6.7%).

36% of patients with ocular manifestation had psoriasis for less than 3years.

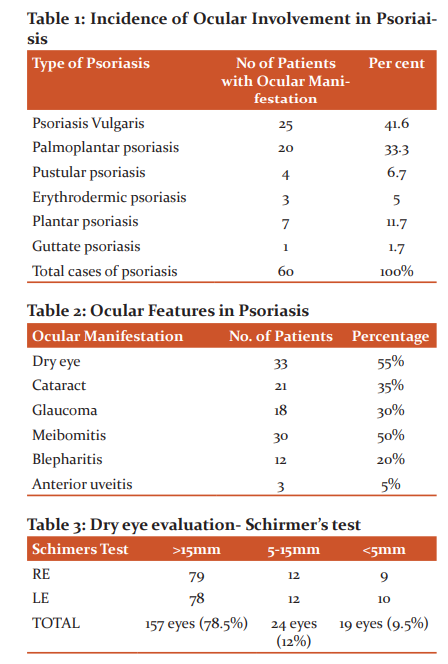

Among our study patients, 22% of the patients were symptomatic, with irritation of eyes being the commonest symptom, followed by water. The various ophthalmic features among psoriasis patients were ocular surface disorder in 33 patients (55%), cataract in 21 patients (35%), meibomitis in 30 patients (50%), blepharitis in 12 patients (20%), and anterior uveitis in 12 patients (20%) (Table 2). Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eye) was most commonly noted.

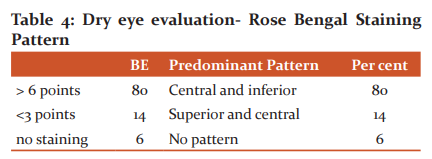

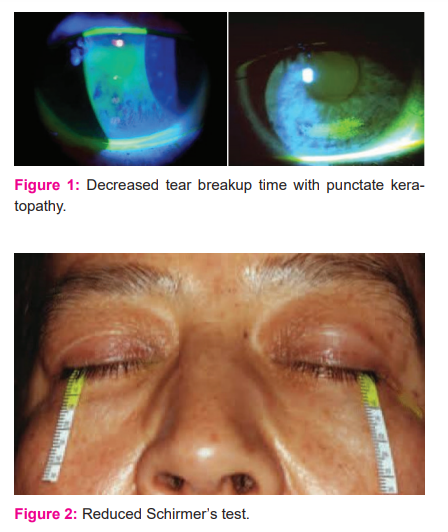

Objective tests for evaluation of the tear film done showed that 43 eyes had abnormal Schirmers test I (Figure 2) indicating reduced aqueous secretion (Table 3). A positive score of greater than 6 on the Van Bijsterveld grading system was seen in 80% of patients (Table 4).58.5% had reduced tear break up time (Figure 1) indicating tear film instability (Table 5). Correlation between tests was calculated using kappa coefficient and statistical significance with a p-value of 0.01 was found in the pattern of conjunctival staining.

The prevalence of blepharitis was 20 %, associated meibomitis was seen in 50%, associated conjunctival keratinization in 2%, anterior uveitis in 12%, and superficial punctate erosion in 9%. None of the patients had peripheral corneal melting.

18 patients (30%) had borderline to high intraocular pressures ranging from 24-36 mmHg. Fundus examination in these patients showed a cup disc ratio of 0.4-0.5 with a normal neuroretinal rim in 47% of patients. Gonioscopy showed an open angle with visualization up to the scleral spur in 73% of patients. The use of topical corticosteroids was noted in the majority of these patients. In those with high IOP, the relationship between the IOP, cup to disc ratios, central corneal thickness, and neuroretinal rim thinning was studied. Steroid-induced glaucoma in 79% and ocular hypertension in 21% were identified. Perimetry in these patients showed nasal step and isolated scotoma in Bjerrum’s area in 3% of patients.

Uveitis was seen in 12%, among whom, 2% had acute uveitis and 10 % had chronic uveitis with old keratic precipitates and posterior synechiae (Table 6). All these patients had unilateral features. All of them were of the anterior type and non-granulomatous. 8% of patients with uveitis had an association with psoriatic arthritis.

Cataract was observed in 21% of psoriasis patients receiving oral steroids (Figure 3). Among them, 9% were less than 40 years. Most cataracts seen were immature senile types, which improved with refraction. The majority of the patients were on treatment with topical steroids (52%) and combined treatment with methotrexate(7%). A dry eye developed in 63% of patients who were being treated with immunosuppressives/ ciclosporin.

DISCUSSION

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory disease that involves multiple organs, predominantly the skin. Among 100 patients, ocular manifestations occurred in 60 patients and were most frequent in psoriasis Vulgaris (54%). In those being referred for ocular complaints, inflammation of the ocular surface and complications of steroid use such as cataract and glaucoma was frequent finding.

Association between psoriatic arthritis and ophthalmic features has been studied previously by Lambert and Wright10 who have reported the incidence as 31.2%, The prevalence of ocular inflammation and uveitis in patients with psoriasis was reported to be 7-20% in a study conducted by Lambert et al., and Knox et al.11, whereas Chandran et al.12, 20078 and Kilic et al.,13 found a prevalence of 2%. Psoriatic arthritis was reported to be 1.5-2.5% in a study conducted by Paiva et al., 200014 and Niccoli et al.,15 Lambert et al., 1979, found that most of their study patients with psoriasis had anterior uveitis (7.1%). In the study conducted by Chandran et al, 2% of patients had uveitis. They also concluded that the presence of absence of uveitis correlated with the Lattice System Physician’s Global Assessment (LS-PGA), prompting an urgent ophthalmic evaluation if the score is greater than 5. Paiva et al concluded that the most common features of uveitis seen in patients with psoriatic arthritis were insidious onset, active bilaterally and posterior uveitis. In our study, arthritis with ocular involvement occurred in 8 patients (8%). Uveitis in psoriasis has been suggested to occur due to a breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier due to subclinical inflammation. The intensity of which is likely to be proportionate to the duration, severity and age of the patient with systemic psoriasis.

We found an abnormal Schirmers test I of less than 5mm in 9.5% and between 5-15 mm in 12 %, indicating decreased aqueous secretion. 48% had reduced tear break up time less than 5 seconds and 10.5% had tear break up time between 5- 10 seconds. Van Bijsterveld score showed scores greater than 6 in 80% of patients with predominance of conjunctival involvement.

Conjunctival staining with Rose Bengal was significant and was more common in the central and inferior zones than superior due to evaporative dry eye.

On analysis, we inferred that in many of our patients, the tear film secretion was normal and the dry eye was because of tear film instability and chronic inflammation of the ocular surface. Goblet cell deficiency, an altered ocular surface and tear film debris was the cause of discomfort in these patients. Superficial punctate erosions and dry spots on the cornea were due to de-epithelialisation which is typical in keratoconjunctivitis sicca.

Squamous blepharitis was found in 20 % and was associated with meibomitis and tylosis. Worsening of symptoms occurred in patients with blepharitis due to secondary changes in the lipid layer of the tear film which resulted in increased evaporation. Meibomitis and blepharitis in psoriasis are due to increased turnover of epithelial cells which is a part of the systemic autoimmune disease process16. Blepharitis was treated with measures for lid hygiene such as warm compression, lid scrubs, topical ocular lubricants and antibiotic ointment. Response to treatment was good in all patients with inflammation clearing within 1 week with no recurrence. Conjunctival keratinisation, tear film debris and superficial punctate erosion was seen in those patients with severe dry eye. This probably occurred due to micro-trauma in the cornea. We did not see blinding or irreversible complications such as corneal ulcers or peripheral corneal melting in any of our study patients.

A common cause of visual loss in patients with psoriasis has been reported as cataracts. In our study, we found both corticosteroid-induced cataract and age-related lenticular changes.

We noted steroid-induced glaucoma in 18%, which responded well with treatment with brimonidine tartrate 0.2% or timolol maleate 0.5% eye drops. Among our study patients, the mean intraocular pressure was within the normal range in 82 patients (82%). 18% of patients had borderline high intraocular pressure (21- 30 mm Hg) due to prior ongoing treatment with topical and/or corticosteroids. These patients with steroid-induced glaucoma had both fundus and visual field changes. Whereas, in the study done on Singaporean patients with psoriasis, the prevalence of glaucoma was 2%.

Ophthalmic involvement and early ocular signs in psoriasis may be subtle and easily overlooked especially in the absence of symptoms. A comprehensive ophthalmic examination needs to be done to detect ocular abnormalities, ocular complications and sequelae of treatment in these patients. In most situations, inflammation can be fully treated with complete resolution with early treatment. Literature states that patients with psoriatic arthritis develop ocular involvement. We observed from our patients that they occur in patients without an arthritic component as well. Hence we recommend that all patients should be evaluated for ophthalmic involvement irrespective of the presence and extent of joint involvement.

Dry eye can be due to the evaporation of tears or aqueous tear deficiency. The combination of dry eye, an unstable tear film and chronicity in these patients with keratoconjunctivitis sicca can predispose to the development of allergic conjunctivitis and meibomitis, which can worsen the ocular surface disease. This cascade of ocular symptoms and discomfort must be detected and treated in the early stages to prevent ocular morbidity.

CONCLUSION-

We found a definite association between duration and severity of psoriasis with ophthalmic features. Visual morbidity due to ophthalmic manifestations can occur both during the active phase of the disease, due to complications after disease resolution or as a consequence of drugs used for the treatment of psoriasis. It is ideal to have a multispecialty approach in the treatment of psoriasis. A combined protocol of screening and timely treatment would benefit the patient in terms of both ophthalmic and holistic care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT- We acknowledge the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. We are also grateful to the authors, editors and publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST- NIL

NIL FUNDING/FINANCIAL INTEREST IN THIS STUDY

References:

1. Cruz NFS da, Brandão LS, Cruz SFS da, Cruz SAS da, Pires CAA, Carneiro FRO. Ocular manifestations of psoriasis. Arq Bras Oftalmol [Internet]. 2018;81(3). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5935/0004-2749.20180044

2. Gibbs S. Skin disease and socioeconomic conditions in rural Africa: Tanzania. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35(9):633–9.

3. Danielsen K, Olsen AO, Wilsgaard T, Furberg AS. Is the prevalence of psoriasis increasing? A 30-year follow up of a population-based cohort. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1303–10.

4. Enno C. Psoriasis: Epidemiology and clinical spectrum. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2001;26:314–20.

5. Lebwohl M, Menter A, Koo J, Feldman S. Combination therapy to treat moderate to severe psoriasis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004;50(3):416-430.

6. Fraga N, Oliveira M, Follador I, Rocha B, Rêgo V. Psoriasis and uveitis: a literature review. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 2012;87(6):877-883.

7. Ajitsaria R, Dale R, Ferguson V, Mayou S, Cavanagh N. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthropathy and relapsing orbital myositis. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2001;26(3):274-275.

8. Zohreh H, Leila S, Soheila S. Management of psoriasis in children: A narrative review. J Pediatr Rev. 2015;3:e131.

9. Agnieszka B, Adam R. The reliability of three psoriasis assessment tools: Psoriasis area and severity index, body surface area and physician global assessment. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26(5):851–856.

10. Lambert JR, Wright V. Eye inflammation in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1976;35(4):354–6.

11. Knox DL. Psoriasis and intraocular inflammation. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1979;77:210-24.

12. Chandran NS, Greaves M, Gao F, Lim L, Cheng BCL. Psoriasis and the eye: prevalence of eye disease in Singaporean Asian patients with psoriasis: Psoriasis and the eye. J Dermatol. 2007;34(12):805–10.

13. Kilic B, Dogan U, Parlak AH, Goksugur N, Polat M, Serin D, et al. Ocular findings in patients with psoriasis: Ocular findings in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(5):554–9.

14. Paiva ES, Macaluso DC, Edwards A. Characterization of uveitis in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:67–70.

15. Niccoli R, Nannini C, Cassara E. Frequency of iridocyclitis in patients with early psoriatic arthritis. A prospective follow-up study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15:771–784.

16. Zengin N, Tol H, Balevi ?, Gündüz K, Okuda S, Endo?ru H. Tear film and meibomian gland functions in psoriasis. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2009;74(4):358-360.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License