IJCRR - 7(21), November, 2015

Pages: 41-46

Date of Publication: 11-Nov-2015

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

ASSESSMENT OF NUTRITIONAL STATUS AMONG ADOLESCENT BOYS (10-19 YEARS) OF SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN AN URBAN AREA OF DISTRICT ROHTAK, HARYANA

Author: Vikas Gupta, Debjyoti Mohapatra, Vijay Kumar

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Background: Census 2011 estimated that there are approximately 253 million adolescents in India, constituting about 20.9% of the total population. Adolescence is an important stage of growth and development in the lifespan. Adolescent is a tender stage which is not only marked by rapid physical growth, but also accompanied by sexual and hormonal turbulence. Inadequate nutrition not only hamper the physical growth but also delay pubertal changes in the body. Methods: This cross sectional study was conducted in the field area of an urban health center, Rohtak, Harayna during the months of January to March 2015. The participants involved were school going adolescent boys 10 to 19 years). The participants were classified as thinness as their under-nutritional status depending upon the Z-score value (WHO growth standards, 2007) of their respective BMI. Results: A total of 649 boy participated in study. Overall mean age of study participants was 15.5 years. The proportion of adolescents who were undernourished based on BMI Z Score came out as 36.7% (13.3% severely undernourished and 23.4% moderately undernourished). Mothers education status was found to have a significant impact on nutritional status of adolescent (P = 0.017). Conclusion: Nutritional status of the studied children is not impressive among adolescent boys, there is a need for health promotion activities in school children by providing an enabling environment and improving nutritional status of the adolescents will go a long way in maintaining the health of the country..

Keywords: Under-nutrition, BMI, Adolescents

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adolescents as individuals aged 10-19 years. The term adolescent is derived from the latin word “adolescere” meaning “to grow up”. As per World Population Prospects, the 2012 revision, there are around 699 adolescents worldwide, comprising 17.3 % of the global population. Every fifth person in the world is an adolescent. Census 2011 estimated that there are approximately 253 million adolescents in India, constituting about 20.9% of the total population. Adolescence is an important stage of growth and development in the lifespan. Adolescent is a tender stage which is not only marked by rapid physical growth, but also accompanied by sexual and hormonal changes. This period is very crucial since these are the formative years in the life of an individual when major physical, psychological, hormonal and behavioural changes take place. Adolescent period may represent a window of opportunity to prepare an adolescent for a healthy adult life. (Tanner) Unfortunately these group of individuals are the most neglected as they are neither children nor adults. Yet they experience a variety of health and social problems like early marriage, teenage pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, drug abuse, juvenile delinquency, injuries, learning disabilities, mental illness and malnutrition. (Kathleen M Kurz) Nutrition is the foundation for good health and development. Malnutrition denotes impairment of health arising either from deficiency or excess or imbalance of nutrients in the body. Generally there are two forms of malnutrition one is under-nutrition and other is over-nutrition. In India nearly 44-47% of adolescents are abnormally thin. (Parasuraman 2009) Inadequate nutrition in adolescence can potentially retard growth and sexual maturation, although these are likely consequences of chronic malnutrition in infancy and childhood. Adolescence is also a period of catch-up growth for previously undernourished children. (op ghai) Calculation of BMI(weight/height2 ) remains a valid tool for epidemiological studies to assess the nutritional status of adolescents. (World Health Organization Physical Status) A large number of national nutritional programs have been implemented to combat the menace of malnutrition, but the gap remains the same. (DK Taneja). There is paucity of studies being conducted among adolescent boys hence this area needs to be further explored. There is also a need to investigate the various socio-demographic and lifestyle factors affecting nutritional status of adolescents and such observations could be utilized into the formulation of programmes and policies. Also at anganwadi centres more priority is given to adolescent girls, keeping more often adolescent boys neglected. Keeping this all in view, the present study was conducted among adolescent boys to assess their nutritional status and to evaluate the associated various factors associated with it.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and the participants: This cross sectional study was conducted during the months of January to March 2015 in the service area of an urban health center, Rohtak which also happens to be field practice area under the aegis of department of Community Medicine, PGIMS, Rohtak, Haryana;. The participants involved were school-going boys (10 to 19 years). All government and private secondary schools were listed and the school principals were approached to obtain permission for conducting the study. Only two government schools provided permission for conducting study and following which interview dates of study were fixed. Both school granted permission to conduct study only from ninth standard onwards. The line listing of students from 9th standard to 12th standard was done for both the schools, total students were about 840. Out of 840 participants, 660 students were included in the study using consecutive sampling. Written informed consent from the parents and assent from the student was obtained.

Data collection: A pretested, predesigned questionnaire was used by the investigator to interview study participants. Information regarding socio-economic profiles was obtained from parents through telecommunication.Assessment of age is most essential for conducting growth studies. The accurate age of the adolescent boys was recorded from the school registration books. The anthropometric measurements of children were done using WHO guidelines (1995). The weight was measured in kilogram (Kg) using bathroom scale with minimum clothing and without shoes having precision of 0.5 kg. It was calibrated against known weights regularly. The zero error was checked for and removed if present, every day. Height in centimetres (cm) was marked on a wall with the help of a measuring tape. All boys were measured against the wall without foot wear and with heels together and their heads positioned so that the line of vision was perpendicular to the body. A glass scale was brought down to the topmost point on the head. The height was recorded to the nearest 1 cm. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kg divided by the square of height in meter (m). Students suffering from an acute illness on the day of study or within a period of 2 weeks prior to the study were excluded. The prevalence of thinning among Indian adolescents in the observation of Parshuranam et al. was around 44%, so sample size was calculated using prevalence as 40% with allowable error as 10% of prevalence and non-response as rate as 10%, total sample size calculated was 660. Sample size calculation= (1.96)2 *p*q / (d)2 , where p is prevalence = 0.4, q is 1-p = 0.6, d is allowable error which is 10% of prevalence = 0.04. The participants were classified as thinness as their under- nutritional status depending upon the Z-score value (WHO growth standards, 2007) of their respective BMI, which was calculated using WHO Anthro plus software. If Z-score < -2 = moderately thinning, Z-score < -3 = severely thinning. This cutoff point has been utilized by several recent studies worldwide on under-nutrition among adolescents. The socio-economic status was obtained using modified B.G. Prasad socioeconomic status classification (revised for year 2014, CPI 2001 as base). There are five classes under this upper class (I) (>Rs.5,357), upper middle class (II) (Rs.2652- 5356), middle class (III) (Rs.1570-2651, lower middle class (IV) (Rs.812-1569), and lower class (V) (Rs.811). (Modified B.G Prasad, Base year 2014)The responses to schedule by each participant were entered into excel sheet and data was tabulated and for statistical analysis using SPSS 16.0, we calculated percentages and applied the Chi-square test wherever necessary and required.

RESULTS

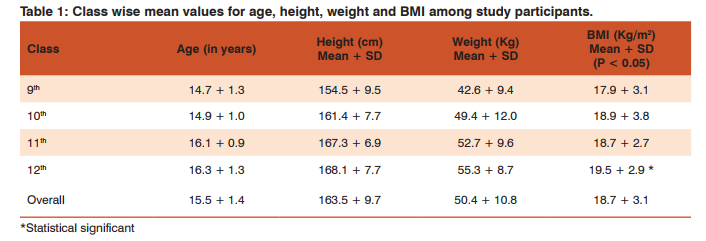

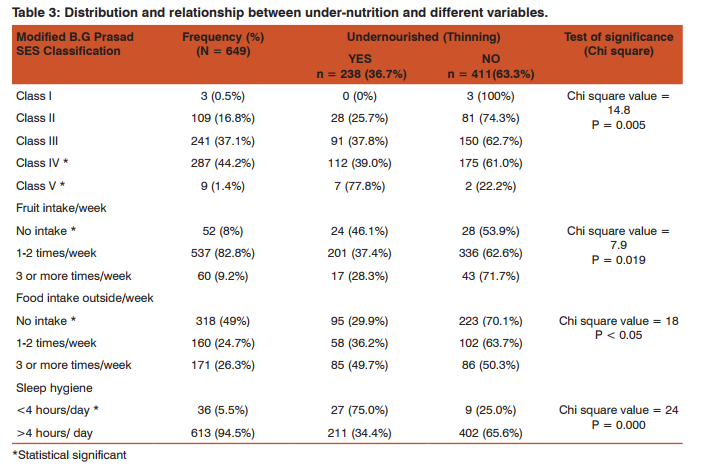

Present study was conducted in two government schools with a total of 649 participants studying in 9th to 12th standards. Overall mean age of study participants was 15.5 years (Table 1).The mean height and weight were calculated for each class group and for all groups together mean height and weight came out as 163.5 cm and 50.4 kg. BMI derived from height and weight was also sorted for individual class groups and it was noticed that for 9thstandard, mean value of BMI(17.9) was lowest and was highest for 12th standard (19.5), and this difference was statistically significant (ANOVA test F-value = 8.9, P <0.05); whereas mean value of BMI for all participants together was 18.7 (Table 1). Based on BMI Z Score, 36.7% of the adolescent boys were found to be undernourished(13.3% severely undernourished and 23.4% moderately undernourished). When undernourished status was derived for age groups, it was found that proportion of undernourished adolescent increases significantly (P <0.05) as the age progresses (Table 2). Nearly every fourth participants belonged to dominant caste. The proportion of undernourished adolescents was significantly (P = 0.02) higher among scheduled caste participants when compared to other categories participants (Table 2); also height (166.6 + 9.3) and weight (53.1 + 10.5) were significantly (ANOVA test for height, F-value = 9.6, P < 0.05), (ANOVA test for weight, F-value = 6.4, P = 0.002) higher among general category participants than other category participants (Scheduled Caste, height 162.5 + 10.3, weight 49.3 + 11.0), (Dominant caste, height 162.7 + 8.1, weight 50.1 + 10.0). While comparing class wise, 11th standard followed by 9th standard were significantly (P <0.05) leading the groups in terms of high proportion of undernourished children. Mother’s education status was found to have a significant impact on nutritional status of adolescent. The proportion (29.8%) of undernourished children was significantly (P = 0.017) lower in those groups of students who had mothers with good education status. The present showed that most participants belonged to Class III and Class IV of Modified B.G Prasad SES Classification and it also revealed significant (P = 0.005) increase in proportion of undernourished adolescents as we move from higher to lower socio-economic class. Adolescents with higher consumption of fruits were having lesser number of under-nutrition rate. Faulty food habits like consumption of food outside/from hawkers/streets and poor sleep hygeine, were more prevalent among undernourished adolescents.

DISCUSSION

Adolescence is an important stage of growth and development that requires increased nutrition. The transition may extend over variable periods of time, depending upon socio economic factors. Even in given culture, adolescents are not a homogeneous group, with wide variations in development, maturity and lifestyle. But it has often failed to get increased attention as observed in childhood with regards to health related uses and interpretation of anthropometry. This study highlights the level of under-nutrition among the school adolescents in male population as opposed to earlier studies considering heterogeneous population. In present study 649 students participated and out of them, 34.6% were having undernourished status. There is huge variation regarding prevalence of under-nutrition in India and it could be due to different standards used to judge the under-nutrition. The prevalence of under-nutrition in the studies of Banerjee et al, (37.8%) Iyer at al (30.5%) and Deka et al (31.5%) were nearby close to present studies, where in studies conducted by Vashisht at al (26.7%) in 2009 and by Bose et al (20.8%) showed lower prevalence. But in studies by Saluja et al(49.5%) and Dasgupta et al (47. 3%) the prevalence was comparatively higher. While moving to mean BMI, in present study it is was clearly observed that, it increases consistently and significantly with progression of age and was in pursue with Dasgupta et al, Kanade et al and Das et al findings. On similar grounds, the prevalence of under-nutrition was significantly more in higher age group than lower age group participants, and this agreement was reflected in Vashisht et al, Haboubi et al, and Deka et al studies but in contrary to Das et al and Deshmukh et al. The caste wise distribution of under-nutrition shows significantly higher prevalence among schedule caste participants (41.1%) in present study and Rajeratnam el al work. An attempt was made to look into some of the variables on the prevalence of under- nutrition and variable studied were socioeconomic status, literacy levels of mother. With progress in both education levels of mothers and socioeconomic status of families, revealed the decreasing trend of under-nutrition among adolescents and was in favor with other studies (Iyer et al, Gupta et al. (SES), dake et al.); and association was found to be significant, but Bhattacahryya et al advised the mother education as more strong indicator than socio-economic status for association with under-nutrition. The dietary behavior or pattern and sleep hygiene variables among adolescents are being much studied for overweight and obesity in India, but in our present study when participants were interviewed about these variables, the adolescents with faulty dietary habits and deranged sleep were significantly more concentrated among undernourished participants and in correspondence to Ahmed et al work. The study represents an adequate sample size and response rate. The WHO Z-Score for BMI was used, to derive the undernourished status (thinning) and inference of under-nutrition with various variables showed statistical significance which reflects the strength of present study. Also the results were shared with the school health promotion advisory boards to generate information on the stakeholders’ perception about the issue and ways to address it. But due to time constraints and conduction of study near to exam months, permission was obtained from very few schools and also the study was limited to only adolescent boys of 9th to 12th standards; so comparison between girls and boys with the various factors was not made. This could be considered as limitation of this study.

CONCLUSION

The study has made an effort to look at some of the important determinants that set apart the nutrition transition. India is a country of stark inequalities in income and health risks. The determinants identified for under nutrition, stresses the role of socioeconomic and dietary factors on nutritional status. So, the variation in proportion and severity of undernutrition is of obvious importance for the formulation of health and development policies at the community level. Therefore there is a need for health promotion activities in school children by providing an enabling environment and improving nutritional status of the adolescents will go a long way in maintaining the health of the country. In conclusion, nutritional status of the studied participants is not impressive among adolescent boys. There is compelling requirement of interventional strategy which creates community based nutrition awareness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the efforts made by principals of both schools in scheduling interviews and for their co-operation. Author acknowledges male multipurpose health workers (MPHW) for their participation in the study. Authors acknowledge the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. The authors are also grateful to authors / editors / publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed.

References:

1. Chandramauli C. Adolescents and Youth in India - Highlights from Census 2011. Proceedings of the Conference commemorating on World Population Day 2014 jointly organized by ORGI and UNFPA; 2014 July 17; Vigyan Bhawan, New Delhi.

2. World Population Prospects: the 2012 revision. United Nations: New York; 2012.

3. India - Population and Housing Census 2011. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner India; Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

4. Tanner JM. Growth at adolescence (2nd ed.) Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1992.

5. Kathleen M Kurz; Symposium on Adolescent Nutrition – Are we doing enough? ; University of Aberdeen; July 1995.

6. World Health Organization. Adolescent Nutrition: a review of the situation in selected South-East Asian Countries. New Delhi: Region of South East Asia, WHO; 2006.

7. Ghai OP, Gupta P, Paul VK. Ghai essential pediatrics, adolescent health and development. Pediatrics 2006;6:66.

8. Taneja DK. Health policies and programmes in India. 11th ed. Delhi: Doctors publications; 2013. p. 98-107.

9. World Health Organization. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry: Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Technical Report Series No. 854. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995.

10. Verma R. Manual of practical community medicine. 2nd ed. Chandigarh: Saurabh Medical Publishers; 2014. p. 7.

11. De Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:660-7.

12. Banerjee S, Dias A, Shinkre R, Patel V. Under-nutrition among adolescents: a survey in five secondary schools in rural Goa. Natl Med J India 2011;24:8-11.

13. Saluja N, Bhatngar M, Garg SK, Chopra H, Bajpai SK. Nutritional status of urban primary school children in Meerut. Int J Epidemiol 2010;8:1-7.

14. Dasgupta A, Butt A, Saha TK, Basu G, Chattopadhyay A, Mukherjee A. Assessment of malnutrition among adolescents: can BMI be replaced by MUAC. Indian J Community Med 2010;35:276-9

15. Iyer UM, Bhoite RM, Roy S. An exploratory study on the nutritional status and determinants of malnutrition of urban and rural adolescent children (12-16) years of Vadodaracity. Int Appl Biol Pharm Technol 2011;2:102-7.

16. Kanade AN, Joshi SB, Rao S. Under nutrition and adolescent growth among rural Indian boys. Indian Pediatr 1999;36:145– 56.

17. Das B, Bisai S. Prevalence of undernutrition among Telaga adolescents: an endogamous population of India. Inter J Biolog Anthr 2008;2:123-9.

18. Deshmukh PR, Gupta SS, Bharambe MS. Nutritional status of adolescents in rural Wardha. Indian J Pediatr 2006;73:139-141.

19. Haboubi GJ, Shaikh RB. A comparison of the nutritional status of adolescents from selected schools of South India and UAE: a cross-sectional study. Indian J Community Med 2009;34:108- 111.

20. Gupta R, Rastogi P, Arora S. Low obesity and high undernutrition prevalence in lower socioeconomic status school girls: a double jeopardy. Human Ecol 2006;14:65-70.

21. Bhattacharyya H, Barua A. Nutritional status and factors affecting nutrition among adolescent girls in urban slums of Dibrugarh, Assam. Natl J Community Med 2013;4:35-9.

22. Deka MK, Malhotra AK, Yadav R, Gupta S. Dietary pattern and nutritional deficiencies among urban adolescents. J Family Med Prim Care 2015;4:364-8

23. Rajaretnam T, Hallad TS. Nutritional status of adolescents in northern Karnataka, India. J Fam Welf 2012:58:11-4.

24. Ahmed F, Zareen M, Khan MR, Banu CP, Haq MN, Jackson AA. Dietary pattern, nutrient intake and growth of adolescent school girls in urban Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr 1998;1:83–92.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License