IJCRR - 7(22), November, 2015

Pages: 01-07

Date of Publication: 21-Nov-2015

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

UTILISATION OF BLOOD COMPONENTS IN A TERTIARY CARE HOSPITAL

Author: Mohammad Zubair Qureshi, Vijay Sawhney, Humiara Bashir, Meena Sidhu, Peer Maroof

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Background: Transfusion of blood components such as Packed Red Cell (PRC), Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP) and platelet concentrates (PC) play an important role as a supportive therapy. This study was performed to study the utilisation and appropriateness of blood components in clinical practice at a tertiary care hospital\?based blood bank at GMC, Jammu. Materials and Methods: A prospective analysis of blood components was conducted over a period of one year from November 2012 to October 2013. The usage of different types of blood component were recorded and correlated with the patient's diagnosis and indications for transfusion. The appropriate use of blood components were assessed by DGHS guidelines. Results: Of the total 17634 units of blood components issued over a period of 1 year, 58.14% were Packed Red Cells (PRC), 29.43% were Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP), 12.25% were Platelet Concentrate (PC) and 0.18% were Cryoprecipitate. The appropriate use of Packed Red Cells was 90.33% whereas inappropriate use was 9.67%. Inappropriate use of PRC was mostlyseen in patients with minor bleeding without significant changes in hemoglobin level and in patients with asymptomatic chronic anemia with Hb > 7g/dl. For Fresh Frozen Plasma 80.66% usage was appropriate and 19.34% were used inappropriately. Use of FFP for volume expansion was the most frequent form of inappropriate use followed by cases of bleeding without derang of coagulation tests. For Platelet Concentrate 93.29% transfusions were utilized appropriately and 6.71% inappropriately. Inappropriate use of PC was mostly seen in patients who had received platelets prophylactically with platelet count above 10,000/\?l. Conclusion: Periodic review of blood component usage is very important to access the blood utilization pattern and judicious implementation of guidelines for use of blood components would decrease their inappropriate use.

Keywords: Packed red cell, Platelet concentrates, Fresh frozen plasma, Appropriate

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Over the last few decades transfusion medicine has underwent marked changes. Contrary to use of whole blood, emphasis is given on the use of specific blood components for appropriate and rational use of blood. The blood component implies separation of whole blood into various components like packed red cells, platelet concentrates, fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate.1 Blood transfusion forms an important part of various treatment protocols. Blood must be transfused cautiously in view of its propensity to cause adverse effects such as introduction of donor antigens in the recipient, transfusion reactions or exposure to various transfusion transmitted diseases. The indications for ordering blood must be fully justified to avoid misuse or overuse of this precious resource. Periodic review of blood component usage is essential to assess the blood utilization pattern2 . Appropriate use of blood components results in cost effective transfusion therapy and reduces transfusion related complications3 . With the advent of blood component usage for specific needs of patients better guidelines have been suggested and put into practice. It is now a standard practice to manufacture and use different blood components from donated whole blood 4 . The current study was prospectively carried out in the Department of Transfusion Medicine at Government medical college (GMC) Jammu from November 2012 to October 2013. It was aimed at studying the utilisation and appropri ateness of various blood components in clinical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Prospective analysis of blood component requisitions in patients from different clinical departments of GMC, Jammu were reviewed regarding age, sex, blood group, diagnosis, investigations, indication for transfusion, number of units issued and the speciality prescribing it. The usage of different types of blood component were recorded and correlated with the patient’s diagnosis and indications for transfusion. The appropriate use of blood components were assessed by Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS-2003) guidelines.

Indications of packed red cells (PRC):

• Surgery: Patient requiring urgent operation with Hb < 10g/dl.

• Anticipated surgical blood loss > 1000 ml.

• Acute blood loss of 30-40% of blood volume or more.

• Anemia associated with incipient or established cardiac failure.

• Hb value < 6 g/dl in the absence of disease and between 8 and 10 g/dl with disease.

• Patients approaching delivery and having Hb value < 7 g/dl.

• In hereditary hemolytic anemias and beta thalassemia major, guidelines are more liberal.

Indications of Platelet concentrate (PC):

• Platelet count is < 5000 / μl regardless of clinical condition.

• Platelet count is 5000-10,000 /μl, if there is increased risk of bleeding due to hematological malignancies, sepsis, severe aplastic anemia or patients undergoing bone marrow transplant.

• Platelet count is 10,000-20,000/μl, if thrombocytopenic bleeding or microvascular bleeding is present.

• Chemotherapy of malignancy (decreased production), if platelet count ≤ 20,000/ μl.

• Disseminated intravascular coagulation (increased destruction), if platelet count is ≤ 50,000/ μl.

• Massive transfusion (platelet dilution), if platelet count is ≤ 50,000/ μl.

• In major surgery if the platelet count is 1.5 × Normal. Indications of Cryoprecipitate:

• Hemophilia A. • Von Willebrand’s disease. • Congenital or acquired fibrinogen deficiency.

• Acquired Factor VIII deficiency (e.g. DIC, massive transfusion).

• Factor XIII deficiency.

• Source of Fibrin Glue used as topical hemostatic agent in surgical procedures. Statistical analysis: Data from blood component requisition forms of Department of Transfusion Medicine was collected, coded, tabulated, analysed and expressed as percentage.

RESULTS

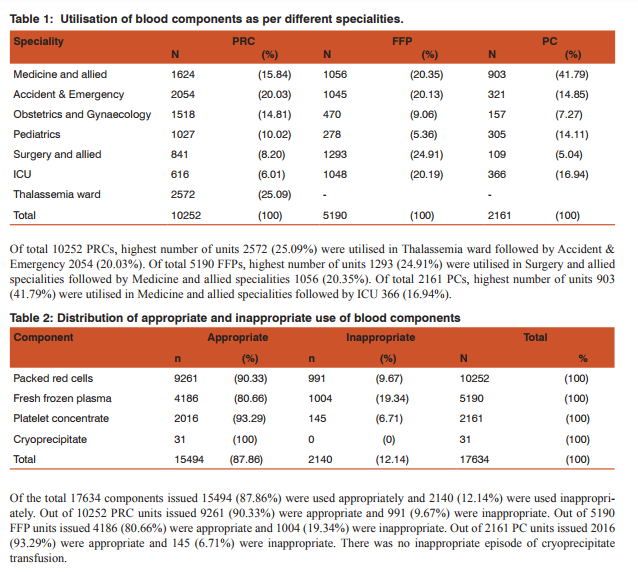

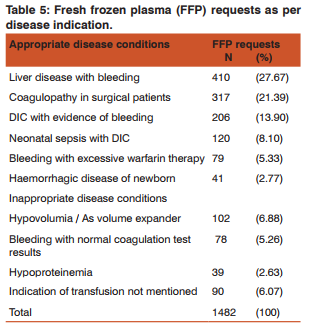

Out of total 10980 transfusion requests, 17634 transfusion units for different blood components were issued. For PRC 8649 (78.77%) transfusion requests were received and 10252 (58.14%) units were issued with an average of 1.18 units per patient. For FFP 1482 (13.50%) transfusion requests were received and 5190 (29.43%) units were issued with an average of 3.50 units per patient. For PC 843 (7.68%) transfusion requests were received and 2161 (12.25%) units were issued with an average of 2.56 units per patient. For Cryoprecipitate 6 (0.05%) transfusion requests were received and 31 (0.18%) units were issued with average of 5.16 units per patient. Of total10980 transfusion requests received 6283 (57.22%) were for males and 4697 (42.78%) were for females. Maximum number of requests 4293 (39.10%) were between 0-15 years of age, 1889 (17.20%) were between 16-30 years, 1372 (12.50%) were between 31-45 years, 1306 (11.90%) were between 46-60 years and 2120 (19.30%) were above 60 years of age. Of total requisitions received 2537 (23.10%) were for A+ve, 3589 (32.69%) were for B+ve, 3156 (28.74%) were for O+ve, 939 (8.55%) were for AB+ve, 190 (1.73%) were for A-ve, 241 (2.20%) were for B-ve, 230 (2.10%) were for O-ve and 98 (0.89%) were for AB-ve.

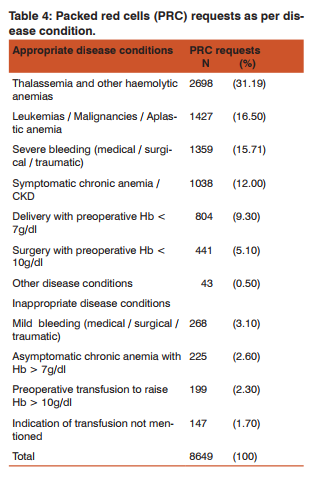

For PRC highest percentage of appropriate episodes 99.18% (2551/2572) were observed in Thalassemia ward followed by ICU 96.75% (596/616), while as highest percentage of inappropriate episodes 22.27% (338/1518) were observed in Obstetrics and Gynaecology followed by Accident and Emergency 16.31% (335/2054). For FFP highest percentage of appropriate episodes 89.03% (933/1048) were observed in ICU followed by pediatrics 86.69% (241/278), while as highest percentage of inappropriate episodes 24.40% (255/1045) were observed in Accident and Emergency followed by Surgery and allied specialities 23.90% (309/1293). For PC highest percentage of appropriate episodes 97% (355/366) were observed in ICU while as highest percentage of inappropriate episodes 8.86% (80/903) were observed in Medicine and allied specialities followed by Accident and Emergency 8.10% (26/321).

DISCUSSION

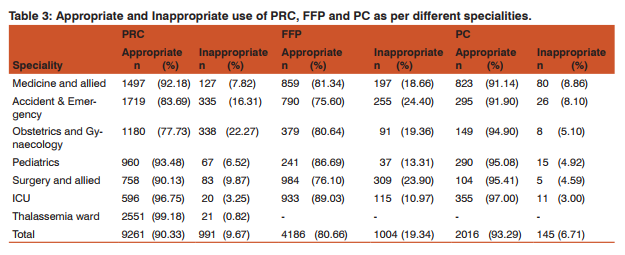

Blood component therapy allows several patients to benefit from one unit of donated whole blood. Blood and blood products are considered drugs by the food and drug admin- istration (FDA). Just like any other treatment strategy with pros and cons, blood transfusions should only be administered if the benefits outweigh the risks5 . As a fact the supply of blood and blood components are finite, a high rate of inappropriate use has been reported around the world. This inappropriate use of blood and its components have a significant impact on the patients and the hospital staff in the form of health care cost, wastage of resources, depriving more needy patients and transmission of infection with unnecessary allergic reaction leading to high mortality and morbidity in patients6, 7. In the current study of the total 17634 components issued 15494 (87.86%) were used appropriately and 2140 (12.14%) were used inappropriately. The rates of inappropriate use of blood components reported by most studies vary widely, and it is difficult to compare rates because of differences in the criteria used to define appropriate and inappropriate use. Each blood product will be discussed separately because of the variety of reasons for transfusing packed red cells, fresh frozen plasma and platelets.

Packed Red Cells (PRC):

The number of requests received for packed cells were 8649 (78.77%) and number of units issued were 10252 (58.14%) with average of 1.18 units per patient. Of 10252 units of PRC issued, 90.33% belonged to a group of appropriate use and 9.67% were used inappropriately. Metz et al8 found 10-16% of transfusion units were given inappropriately and Mozes et al.9 reported a much higher rate of inappropriate use of PRCs. Maximum appropriate use of PRC (99.18%) was in patients with thalassemia followed by ICU patients (96.75%). It may be due to the fact that in beta thalassemia major, guidelines for transfusion are more liberal and in ICU proper transfusion guidelines may have been followed. Obstetrics and Gynaecology department (22.27%) followed by Accident and Emergency department (16.31%) were the main inappropriate users of PRC. Transfusions of packed red blood cells was found to be inappropriate in patients with evidence of bleeding but without significant changes in hemoglobin level, in patients with asymptomatic chronic anemia with Hb > 7 g/dl and in patients who had received transfusions preoperatively to raise Hb > 10 g/dl.. In many instances a low hemoglobin or hematocrit is used to determine a request for a transfusion of packed red cells but the correct approach is to combine the laboratory criteria and the symptoms of the patient. Clinical transfusion therapy relies on clinical experience and investigation. Recently, new evidence-based transfusion guidelines (“triggers”) have been promoted to rationalise blood utilisation and reduce harmful transfusion complications10.

Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP):

The number of requests for FFP were 1482 (13.50%) and number of units issued were 5190 (29.43%) with average of 3.50 units per patient. It is recommended to transfuse 5-6 units of FFP to correct the haemostatic defect due to clotting factor deficiency11. Of these 5190 units of FFP 80.66% belonged to a group of appropriate use and 19.34% were used inappropriately. Percentage of inappropriate use of FFP was high compared to other blood products. Drastic reduction in the use of whole blood has been reported as the origin of inappropriate use of FFP12. There are many reports available regarding inappropriate transfusion of FFP at various centres showing 29% to 40% FFP being used inappropriately 13, 14 ,15 which was higher as compared to our study. We found maximum inappropriate use of FFP in Accident and Emergency department (24.40%) followed by Surgery and allied specialities (23.90%). A coagulation deficiency determination must be performed before request for FFP is made. FFP was given inappropriately as a volume expander, in cases of bleeding without derangement of coagulation tests and in patients of hypoproteinemia. A misconception about FFP that, it is a good volume expander and a source of albumin does not hold true. In our experience, we found two common reasons behind the inappropriate use of FFP. Some clinicians were not aware of the guidelines, while some clinicians tend to use FFP as a “precaution” against litigations and disputes. Kakkar et al.16 indicated 60.3% FFP prescriptions were inappropriate which however got reduced to 26.6% after educational campaigns of clinicians. In present study 6.07% of patients appeared to have been given FFP for reasons not clearly specified. Comparable data has been reported at national and international levels.17, 18, 19 FFP sometimes is still over-prescribed and strict clinical criteria for the utilisation of FFP need to be enforced. To establish an appropriate use of FFP, all requests needs to be sufficed with the indications for FFP as well as the patients Partial Thromboplastin Time (PT) / Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT) and International Normalized Ratio (INR) values.

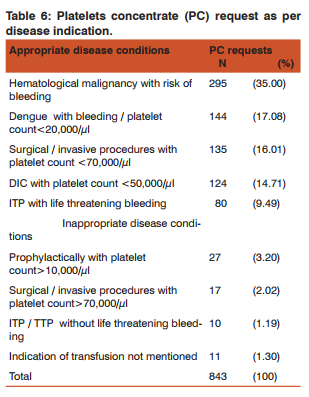

Platelet Concentrate (PC):

The total number of platelet requests received were 843 (7.68%) and number of units issued were 2161 (12.25%) with average of 2.56 units per patient. We found that 93.29% of the platelet transfusions were utilized appropriately and 6.71% inappropriately. Inappropriate use of platelets was seen mostly in Medicine and allied specialities (8.86%) followed by Accident and emergency (8.10%). Makroo et al20 found about 19% of platelet transfusions were given at values in the order of 50-100 × 109 /L and significant percentage of blood request forms were incomplete.

The goal of the platelet transfusions is to prevent severe and life threatening bleeding in patients with thrombocytopenia. This aim needs to be balanced against the risk associated with platelet transfusions as well as the challenge of maintaining an adequate supply.21 In present study inappropriate use of platelets was seen in patients who have received platelets prophylactically with platelet count above 10,000/µl, in surgical or invasive procedures with platelet count > 70,000/ µl, in ITP / TTP without life threatening bleeding. Estcourt et al.22 found 34% of prophylactic transfusions were inappropriate which was higher as compared to our study. It is believed that the use of prophylactic platelet transfusions to keep the platelet count above 10x109 /L reduces the risk of haemorrhage as effectively as keeping it above any higher level.23 On the other hand, in the presence of factors such as fever or infection, ongoing chemotherapy, concurrent coagulopathy, rapid fall in platelet counts or in the presence of potential bleeding sites as a result of surgery, the use of platelet transfusions to keep the count above 20x109 /L is clinically justified.24 During the last two decades all over the world platelet utilization has increased more than the use of any other blood components.25 On one hand, the ready availability of platelet concentrates has undoubtedly made a major contribution to modern clinical practice in allowing the development of intense treatment regimens for hematological or other malignancies and on the other hand inappropriate use is also prevalent.26

CONCLUSION

Periodic review of blood component usage is very important to access the blood utilization pattern in any hospital. Judicious implementation of guidelines for use of various blood components would help decrease their inappropriate use. This will not only ensure availability of proper components to needy patients but simultaneously decrease transfusion related reactions as well. Awareness and education among all treating doctors, establishment of guidelines and regular audit will help in increasing the appropriate use of blood components.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Authors acknowledge the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. The authors are also grateful to authors / editors / publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed

References:

1. Luk C et al. Prospective audit of the use of fresh-frozen plasma. Based on Canadian Medical Association transfusion guidelines. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 2002; 166:1539–1540.

2. Dushyant Singh Gaur, Gita Negi, Neena Chauhan, et al. Utilization of blood and components in a tertiary care hospital. Indian Journal of Hematology and Blood Transfusion. 2009; 25(3):91- 95.

3. Alving B, Alcorn K. How to improve transfusion medicine, a treating physician’s perspective. Arch Path Med 1999; 123:492– 5.

4. Zimmerman R, Buscher M, Linhardt C, et al. A survey of blood Component use in a German university hospital Transfusion 1997; 37:1075-1083.

5. Hawkins TE, Carter JM, Hunter PM. Can mandatory post transfusion approval programme be improved Transfusion Medicine 1994; 4: 45-50.

6. Joshi GP et al. Audit in transfusion practice. 19. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 1998, 4:141–146.

7. Cheng G, Wong HF, Chan A, et al. The effects of a self-educating blood component request form and enforcements of transfusion guidelines on FFP and platelet usage. Clin Lab Haem 1996; 18: 83-87.

8. Metz J, McGrath KM, Copperchini ML, et al, Appropriateness of transfusion of red cells, platelets and fresh frozen plasma. An audit in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Med J Aust. 1995; 162:572–3.

9. Mozes B, Epstein M, Ben Bassat I, et al. Evaluation of appropriateness of blood and blood products transfusion using present criteria Transfusion 1989; 29: 473-476.

10. Tinmouth A, MacDougall L, Fergusson D, et al. Reducing the amount of blood transfused. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:845– 52.

11. Greene E, McCullough J, Weisdrof D. Platelet utilization and the transfusion trigger: A prospective analysis. Transfusion 2007; 47:201-205.

12. Blumberg N, Laczin J, Mellican A, et al. A critical survey of fresh-frozen plasma use. Transfusion 1986; 26: 511-513.

13. Makroo RN, Raina V, Kumar P, et al. A prospective audit of transfusion requests in a tertiary care hospital for the use of fresh frozen plasma Asian Journal of Transfusion Science 2007; (1)2: 59-61.

14. Pratibha R, Jayaranees S, Ramesh JC, et al. An audit of fresh frozen plasma Usage in a tertiary referral centre in a developing country Malays J.Pathol 2001; 23: 41-46.

15. Chaudhary R, Singh H, Verma A, et al. Evaluation of fresh frozen plasma usage at tertiary Care hospital in north India ANZ. J. Surgery 2005; 75: 573-576.

16. Kakkar N, Kaur R and Dhanoa J. Improvement in fresh frozen plasma /transfusion transfusion practice: results of an outcome audit. Transfus Med 2004; 14:231-5.

17. Schofield WN, Rubin GL, Dean MG. Appropriateness of platelet, fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate transfusion in New South Wales public hospitals. Med J Aust 2003; 178:117-21.

18. Beloeil H, Brosseau M,Benhamou D. Transfusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP): audit of prescriptions. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2001; 20: 686-92.

19. Hameedullah, Khan FA and Kamal RS. Improvement in intra operative fresh frozen plasma transfusion practice-impact of medical audits and providing education. J Pak Med Assoc 2000; 50:253-6.

20. Makroo RN, Mani RK, Raina V, et al. Use of blood components in critically ill patients in the medical intensive care unit of a ter- tiary care hospital. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2009 July; 3(2): 82–85.

21. Estcourt LJ, Stanworth SJ, Murphy MF. Platelet transfusions for patients with haematological malignancies: who needs them? Br J Haematol 2011; 154(4):425–40.

22. Estcourt L.J, Birchall J, Lowe D. Platelet transfusions in haematology patients: are we using them appropriately? Vox Sanguinis a International Society of Blood Transfusion 2012; 10:1-10.

23. Schiffer CA. Prophylactic platelet transfusion. Transfusion 1992; 32: 295-8.

24. Slichter SJ. Controversies in platelet transfusion therapy. Annu Rev Med 1980; 3 1: 509-40.

25. Wallace EL, Churchill WH, Surgenor DM, et al. Collection and transfusion of blood and blood components in the United States, 1994. Transfusion 1998; 38:625-36.

26. Freireich EJ. Supportive care for patients with blood disorders. Br J Haematol 2000; 111:68-77.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License