IJCRR - 13(13), July, 2021

Pages: 85-90

Date of Publication: 05-Jul-2021

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

Assessment of Caregiver's Needs and Burden among Family Caregivers of the Terminally Ill Cancer Patients - A Cross-Sectional Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Eastern India

Author: Pany S, Patnaik L, Sahu T

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Introduction: Care within the home usually relies primarily on a family member or friend. Indeed, without the support of a family caregiver, home palliative care would be impossible. Objectives: To assess caregiver's needs and burden among family caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients. Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted in a tertiary care hospital from July 2015 to September 2017 using a predesigned and pretested schedule. Among family caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients admitted to the hospital, one family member was considered, who was primarily responsible for providing care to the patient. A total of 110 family caregivers were included in the study. The analysis was done using SPSS v. 20.0. Results: Most of the family caregivers were either children (35%) or spouse (23.6%) of terminally ill patients and the average caring time was 4.3 hours per day. 97% of people did not receive any practical help from anyone outside the family. As high as 69% of people were in need of maximum support from physicians or other trained professionals to provide optimum care to their loved ones. About 40% of the people experienced severe burden in the process of caring for their loved ones and they were at high risk of developing psychosomatic symptoms. Conclusion: The family caregivers lack appropriate training and knowledge for providing optimal care to their loved ones in a state of advanced illness. They should be trained about providing better palliative care services and support.

Keywords: Carers, Care providers, Home palliative care, End of life care, Terminally ill, Caregiver’s need

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

"Palliative Care is the active total care of patients whose disease is not responsive to curative treatment. Control of pain and other symptoms, the psychological, social and spiritual needs of the patient are paramount".1,2 The goal of palliative care is the achievement of optimal symptom control, the best possible quality of life, as well as appropriate rehabilitation for the patients, their family. Each year an estimated 40 million people need palliative care, 78% of whom live in low- and middle-income countries.2

Palliative care affirms that death should be dignified and the existing is to be fulfilled by a joint committee of the medical fraternity and family members, and appropriate government policy.3,4 There is evidence to support the case that most patients would prefer to die at home.5,6There is a growing trend for people with a terminal illness to remain at home, where practicable. Death may occur in the hospital, but much of the detoriatingphase occurs when the patient is at home. Home palliative care would be impossible for most people without the support of family caregivers. In the United States, in two Gallup Polls, in 1992 and 1996, around 90 per cent of respondents reported that they would prefer home care if they were critically ill for six months.7Despite the input offered by professional palliative care services, care within the home usually relies primarily on a family member or friend. Indeed, without the support of caregivers, home palliative care would be impossible for many people. A study conducted on 18,222 people in Canada shows 88% of people willing to die at the home rather than hospital setting towards the end of their life.7 The trend to die at home is further increasing as a study in Melbourne reports 94.3% inclination to die at home.8

A family caregiver” is a relative or friend who provides psychosocial and/or physical assistance to a patient who needs palliative care.9 The responsibility of a family carer depends on the physical and psychosocial needs of the patient.9,10,11 Family caregiver’ responsibilities may include personal care (hygiene, feeding); domestic care (cleaning, meal preparation); auxiliary care (shopping, transportation); social care (informal counselling, emotional support, conversing); nursing care (administering medication, changing catheters); and planning care (establishing and coordinating support for the patient). the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness of a family member is their first major confrontation with death for many families.12

The physical, emotional, financial and social impact of providing care for a dying relative may be increased by social burdens such as restrictions on personal time, disturbance of routines and diminished leisure time among family caregivers. Relatives of cancer patients may experience as many psychological problems as per some studies which include anxiety, depression, reduced self-esteem, feelings of isolation, mental fatigue, guilt and grief. Caregiving in the family can have a negative impact on the family’s quality of life. Family members of cancer patients may insight many mental issues according to certain studies which incorporate tension, depression, decreased confidence, sensations of disconnection, mental weakness, guilt and sorrow. On contrary, providing care in a family affect the family's satisfaction.9 Presently home palliative care include a more intricate consideration which incorporates advanced skill, for example, opioid administration and management of symptoms. The physical and psychosocial needs of the patient and the elements of connection among career and patient are significant components for caregiving.9,10,11 Diagnosis of a life-threatening disease of a relative is their first significant encounter with death.12Almost one-third of 106 Australian family caregivers reported confronting significant anxiety, and 12% experienced significant depression.13 Being a family caregiver may also predispose a person to health problems, such as physical exhaustion, fatigue, insomnia, burn out and weight loss.

Being a family carer may likewise incline an individual to medical issues, like actual weariness, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, burnout and weight reduction. The patient is more comfortable at the home than in the medical clinic. Demise in the home is a more honourable and agreeable experience than death in hospital. Home palliative care is savvier and numerous medical care centers promote home palliative care. One study has shown that demise among 16% of malignancy patients in South Australia was at home12 and a study in Victoria shown that 21% of individuals die at home.14 It was seen in a study that men are more likely to die at home. Elements for the inclination of home demise were satisfactory monetary assets, having malignancy or AIDS, having a full-time career, not living alone, having individual requirements that could be overseen at home.13,9

In Odisha, the paucity of palliative care units has severely affected thousands of cancer patients and their family members. Limited studies are available assessing caregiver’s needs and burden among family caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients in Odisha.

AIM: To assess caregiver’s needs and burden among family caregivers of the terminally ill cancer patients

SUBJECTS AND METHODS:

Study design:

The study was a hospital based Cross-sectional study conducted in Oncology (Medical and Surgical) and Haematology Departments of Institute of Medical Sciences & SUM Hospital, Bhubaneswar, Odisha. The study was conducted over two years and three months, starting from July 2015 to September 2017. The study population comprised of family caregiver of terminally ill patient. The sample size was calculated to be 110 depending upon the prevalence of terminally ill patients among all cancer patients which was 80% taken from a multicentric study by David S et al.15 To assess awareness, perception and practice of palliative care among family caregivers one family member was considered, who was primarily responsible for providing care to the patient. In this way, 110 family caregivers were included in the study. Family caregivers not willing to participate in the study were excluded.

Data collection and analysis:

Based on the clinical assessment the physicians, terminally ill cases (with survival less than one year) were identified and their caregivers were interviewed. The attendant/s present with them was asked for participation (as family caregivers) and only one was considered for participation (considering that the patient attendant present was more intimately attached in care providing than the other). In this way, a total of 110 family caregivers were interviewed. Data were collected by predesigned and pretested schedule. The subjects were explained in detail about the study and the expected outcome. They were assured of privacy and confidentiality of data. Informed written consent was obtained. The interview was conducted in the local language after establishing a good rapport with subjects and in a very friendly manner.

The data collected were entered in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. After proper data cleaning data were imported and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics software version 20 licensed to the institute. Descriptive statistics were expressed as frequencies (percentages), means, standard deviations, standard error of means at 95 confidence intervals.

Study tool: The schedule for family caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients consisted of basic information of family caregivers, needs of family caregivers and burden assessment of family caregivers. The questionnaire focused on the primary family caregiver and included three parts. The first Part included questions on the interpersonal relationship between the caregiver and the terminally ill, financial status of the caregiver, additional help received outside the family, etc. The second part of the questionnaire was adapted from “The carer support needs assessment tool” (CSNAT) which is a comprehensive evidence-based tool. It is used as part of a process of assessment and support that is practitioner facilitated but carer-led. The CSNAT approach provides carers with the opportunity to consider, express and prioritize their support needs.16 The developers of this tool are Gail Ewing and Gunn Grande who work as social workers at tat the University of Cambridge and the University of Manchester respectively. The thipart Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (BSFC) is a scientifically developed instrument designed to measure the perceived burden of family caregivers resulting from home care.17

Ethical considerations:

Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Institute of Medical Sciences & SUM Hospital with reference number IMS/IEC/108/2015.

RESULTS

A total of 110 family members were interviewed who were present along with the terminally ill patients during the time of the survey.

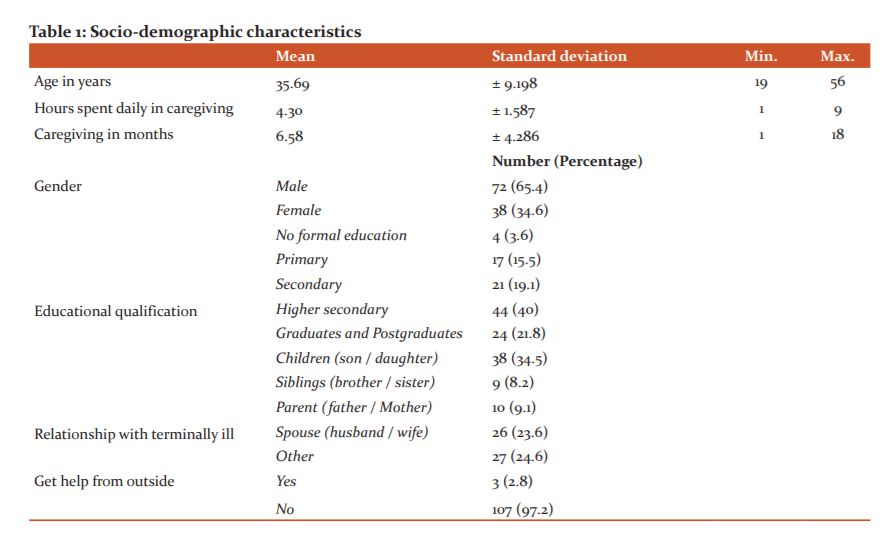

The mean age of the participating family caregivers was 35.69 years with a standard deviation of ± 9.198 years. The minimum among all the caregivers was 19 years while the maximum age was 56 years. The average hours spent in caregiving ranged from 1 hour to almost 9 hours a day with a mean time of 4.3 hours. The family caregivers that were interviewed did spend an average of 6.58 months with their terminally ill relative and some had a fresh experience of at least a month and some were consistently caring for about one and half years. Most of the family caregivers were male (65.4%). Completion of higher secondary examination was seen in many participants (40%), followed by graduates and postgraduates (21.8). Either of son or daughter (34.5%) in the family was the prime caregiver in the family among most of the study participants; while others included siblings (8.2%), Parents (9.1%), spouse (23.6%), grandchildren (12.4%) and other first-degree family relatives (12.2%). Almost all (97.2%) family caregivers had received no external help outside of the family, neither in terms of finances nor in terms of care providing. The few (2.8%) those who had received some sort of help were from local charitable organisations or personal donations made to the families. (Table 1)

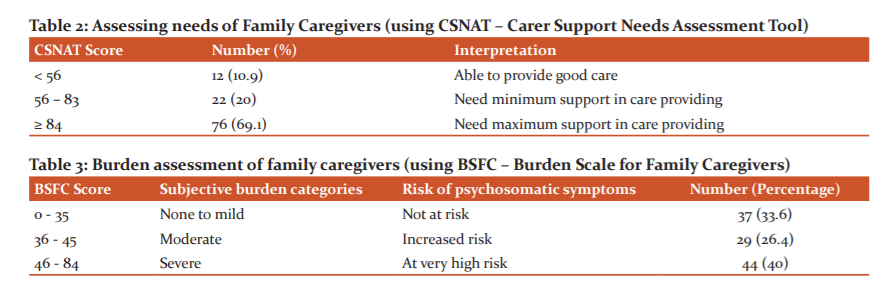

The CSNAT is an evidence-based tool that facilitates support for family caregivers of adults with life-limiting conditions. Based on CSNAT scoring the family members were divided into three categories; scores <56 indicated that the family caregivers could provide good care to the family which included only 10.9% of the total participants, while the score from 56 to 83 including 20% of the family members and this group could even care better if they were supported a little in terms of caregiving. The third group (scores ≥ 84) comprised of the majority of subjects (69.1%) who want a lot of support in providing care to their terminally ill family member. (Table 2)

The burden experienced by the family caregivers is the most important caregiver related variable in care at the home of a terminally ill person. The extent of subjective burden has both emotional and physical impact on the caregiver. The majority (40%) had a severe burden in caregiving and were at higher risk of developing psychosomatic symptoms. Almost a similar percentage (33.6%) of family caregivers experienced none or milder burden in caring for their dear ones and hence they were at minimal risk of developing psychosomatic symptoms. (Table 3)

DISCUSSION:

The mean age of family caregivers was 35.69 ± 9.198 years, minimum among all the caregivers was 19 years while the maximum age was 56 years which highlights that in some families almost a teenager and some almost a geriatric aged group also acted as caregivers to the terminally ill. The average time that was spent for daily caregiving ranged from 1 hour to almost 9 hrs (mean = 4.30 hrs.). As stated in research by Dr.Tse Man Wah & Doris was that if a particular caregiver spends more than 3 hours in caregiving regularly, then he/she is ought to experience a certain form of subjective burden because of caregiving and may be at risk of developing certain negatively impacted psychiatric manifestations.18

About two-third of caregivers were male (65.4%). Children of the terminally ill acted as caregivers in the majority of the cases (34.5%), followed by the spouse (26.7%) and other family members (24.6%). As high as 97.2% of participants claimed to receive no help outside the family and only those few who received help were from local NGO’s and donations made by some noble persons in the society.

Caregivers need was assessed by using CSNAT (Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool). Family caregivers need to be supported in their central role of caring for patients at the end of life, but brief practical tools to assess their support needs have been missing.16Results obtained from it showed 69.1% of family caregivers are in the maximum need of support in care providing for their near ones. While only 10.9% were only able to successfully provide the utmost care that is needed for the terminally ill patient. Research showed that as high as 80% of people require help (physical, psychological and skill-based) to improve the quality of care that they are currently providing to their loved ones. Thishighoutcome of family carers needing much support in care providing is because there is a lack of training of family caregivers and communication between the medical care providers and family caregivers.19

Caregiving burden is often referred to as the family caregivers’ perceived level of distress, demands, and the pressure associated with caregiving roles, responsibilities, and tasks. In this study, using Burden scale for family caregivers revealed that 40% had a severe burden in caregiving and were at higher risk of developing psychosomatic symptoms, 26.4% had moderate burden of caregiving and were at moderate risk to develop psychosomatic symptoms & 33.6% of family caregivers experienced none or milder burden in caring for their dear ones and hence they were at minimal risk of developing psychosomatic symptoms. A study using the BSFC, shown that 7.6% of the caregivers experienced a “no to low” burden, 23.5% “mild to moderate”, 41.8% “moderate to severe” and 27.1% “severe” burden.20 Current medical policy encourages short-term hospital stay and promotes community care for patients with a terminal illness. Family members are the main support system and shoulder the responsibility for patient care in the community.17 The personal impact of the end of life care for terminally ill patients needs to be emphasized.20 In our findings family burden is seen less as it is in our cultures that caring for our relatives is a privilege and love shown to them rather than considering it a burden.

CONCLUSION

Our study indicates that the majority of the family caregivers were either children (35%) or spouse (23.6%) of terminally ill patients and the average caring time was 4.3 hours per day. 97% of people did not receive any practical help from anyone outside the family. As high as 69% of people needed maximum support from physicians or other trained professional to provide optimum care to their loved ones. About 40% of the people experienced severe burden in the process of caring for their loved ones and they were at high risk of developing psychosomatic symptoms.

Caregiving attitude is deep-rooted in our cultures and each member of the family gave their maximum help and love towards their terminally ill patients, but they lacked appropriate training and knowledge in how to provide optimal care to their loved ones in their state of advanced illness. The families must be educated, and some members should be trained about providing better palliative care services and support to their loved ones. Family caregiver’s mental health also should be taken care of by providing counselling and psychosocial support.

LIMITATIONS:

A limitation of this study was that, it was carried out in only one centre. Research by qualitative methods would yield more information and could have brought into limelight what more could be done for family caregivers of the terminally ill cancer patients.

Financial support and sponsorship: Self-funded.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We extend our sincere thanks to the study participants for their support and involvement in the study. We acknowledge Siksha ‘O’ Anusandhan Deemed to be University for their support while doing the research work.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding: Self-funded

Contribution of authors:

-

Dr Subraham Pany: Concept and design, Collection and interpretation of data, Drafting the article, Final approval of the version to be published.

-

Dr Lipilekha Patnaik: Concept and design, Collection and interpretation of data, Drafting the article, Final approval of the version to be published.

-

Dr TrilochanSahu: Concept and design, Drafting the article, Collection and interpretation of data, Final approval of the version to be published.

References:

-

Sepulveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative care: The world health organization’s global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(2):91–6.

-

WHO | Palliative Care [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs402/en/

-

Kassa H, Murugan R, Zewdu F, Hailu M, Woldeyohannes D. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice and associated factors towards palliative care among nurses working in selected hospitals, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC PalliatCare. 2014;13(1):6.

-

Gopal KS, Archana PS. Awareness, Knowledge and Attitude about Palliative Care, in General, Population and Health Care Professionals in Tertiary Care Hospital. Int J Sci Stud. 2016;3(10):31-5.

-

Townsend J, Frank AO, Fermont D, Dyer S, Karran O, Walgrove A et al. Terminal cancer care and patients’ preference for place of death: a prospective study. Bri Med J. 1900;301(6749):415–7.

-

Campbell NC, Elliott AM, Sharp L, Ritchie LD, Cassidy J, Little J. Rural factors and survival from cancer: analysis of Scottish cancer registrations. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(11):1863–6.

-

Canadian Medical Association. CMAJ?.1985. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Care at the End of Life; FieldMJ, Cassel CK, editors. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1997. 2, A Profile of Death and Dyingin America. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK233601/

-

Ben-Aharon I, Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M, Leibovici L, Stemmer SM. Interventions for Alleviating Cancer-Related Dyspnea: A Systematic Review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(14):2396–404.

-

Hudson P. Home-based support for palliative care families: challenges and recommendations. Med J Aust 2003; 179 (6): S35.

-

Standards for Providing Quality Palliative Care for all Australians. Palliative Care Australia May 2005. ISBN 0-9752295-4-0.

-

Higginson IJ, Bs B, Finlay IG, Goodwin DM, Hood K, Edwards AGK, et al. Is There Evidence That Palliative Care Teams Alter End-of-Life Experiences of Patients and Their Caregivers? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(2) :150-68.

-

Hunt R, Fazekas B, Luke C, Roder D. Where patients with cancer die in South Australia, 1990-1999: a population-based review. Med J Aust. 2001;175:526-29.

-

Alexander K, Goldberg J, Korc-Grodzicki B. Palliative Care and Symptom Management in Older Patients with Cancer. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(1):45–62.

-

Clifford CA, Jolly DJ, Giles GG. Where people die in Victoria. Med J Aust. 1991; 155:446-56.

-

David S. Poor palliative care in India.Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(6):515.

-

Ewing G, Brundle C, Payne S, Grande G; National Association for Hospice at Home. The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for Use in Palliative and End-of-life Care at Home: A Validation Study. J Pain Symptom Man.2013;46(3):395-405.

-

17.New: Burden Scale for Family Caregivers in 20 European languages. Available at: www.virtualhospice.ca › Assets › BSFC_english_o.

-

Vulnerability of family caregivers. Palliative Medicine Grand Round, HKSPM Newsletter 2007;1(2).

-

Ewing G, Austin L, Diffin J, Grande G. Developing a person-centred approach to carer assessment and support. Br J Community Nurs. 2015;20(12):580-4.

-

Park CH, Shin DW, Choi JY, Kang J, Baek YJ, Mo HN et al. Determinants of the burden and positivity of family caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients in Korea. Psychooncology. 2012;21(3):282–90.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License