IJCRR - 13(11), June, 2021

Pages: 18-26

Date of Publication: 04-Jun-2021

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

Determinants of Stunting and Wasting Among the Children Under Five Years of Age in Rural India

Author: Abhay Gaidhane, Pratiksha Dhakate, Manoj Patil, Quazi Syed Zahiruddin, Nazli Khatib, Shilpa Gaidhane, Sonali Choudhary

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Background: Stunting and Wasting are effects of undernutrition in early childhood and their prevalence among rural under-5 children is an issue of special concern, especially in a district like Wardha which is known for repeated droughts and the notable number of farmer's suicides. Children with wasting and stunting reflect poor health outcomes in future. Developmental impairment is one of the prominent public health problems in developing countries is the impaired developmental status of children under 5. and its effects can be permanent. Objective: To find out the prevalence and determinants of stunting and wasting among children under five years of age in the rural area of Wardha District of Maharashtra. Methods: Community-based cross-sectional study conducted among children aged from 1-month to 60-months (Under-5 years) in the rural area of Wardha district. Results: A total of 594 children were included in this study among which, 300 (50.5%) were males and the remaining 294 (49.5%) females. 122 (20.54%) children had wasting & 256 (43.09%) children had stunting. The overall study revealed more cases of stunting & fewer cases of wasting from the rural area of the Wardha district. A significant association was found between the prevalence of stunting and the age group. The proportion of children with severe stunting and wasting were maximum in the age group of 1 to 3 years. A significant association was found between stunting and initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth. A significant association was found between the prevalence of wasting and exclusive breastfeeding. Conclusion: The overall study shows that the scenario of stunting and wasting is similar across India. Future health promotion and education programs in Anganwadi centres should include a focused emphasis on good nutrition, IYCF practices and aware�ness campaigns for parents about undernutrition and its future consequences.

Keywords: Stunting, Wasting, SUW (severe underweight), SAM (severe acute malnutrition), MAM (moderate acute malnutrition), Children under-5.

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Globally, 52 million children under five years are moderately or severely wasted (low weight for height). A report by UNICEF published in 2006 states that around 146 million children in developing countries are underweight - that is one out of every fourth child.1-3 One in four children under age 5 (165 million or 26 per cent in 2011) is stunted. Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia are contributing to three-quarters of the world’s stunted children.4 In 2011, five countries that count the highest numbers of stunted children were: India (61.7 million), Nigeria (11 million), Pakistan (9.6 million), China (8 million) and Indonesia (7.5million). Southern Asia reflected the highest prevalence of wasting where one in six children was found severely or moderately wasted. During this period, 25 million children in India were reported to be wasted.5,6 Despite global efforts for improving maternal and child health malnutrition among children remains a significant problem. In India, nearly 48%, 43%, and 20% of children under five years of age are stunted, underweight, and wasted, respectively. Out of these around one fourth are severely stunted.7

It is well documented that chronic undernutrition is associated with serious developmental and health impairment later in life which reduce the quality of life.2,8 Tragically, more than a third of child deaths and greater than 10% of the total global disease burden is attributed to maternal and child undernutrition, which includes underweight, stunting, wasting, and deficiencies of essential vitamins and minerals.4

This study was conducted to find out the prevalence, socio-demographic, environmental and behavioural determinants for stunting and wasting among children under five years of age from rural areas of Wardha district.7,8

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the rural area of Wardha district. Data was collected from a sub-centre area comprising of 6 villages. Study participants were children under five years of age and the respondents were the mother of the eligible children. All children between one month to five years of age and residing in the study area were included after the written informed consent from their mother or parents. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Respondents were assured about the confidentiality of the information and its intended use for research purpose only.

A structured questionnaire was used to collect data. A questionnaire was prepared in English and was then translated into Marathi and was back-translated into English. The questionnaire was pilot tested. Data on socio-demographic profile of the child, mother and household, information on environmental and behavioural determinants such as sources of water, sanitation, handwashing, water purification at household level and information regarding antenatal services received by mother and feeding practices were collected.

After data collection, the child’s height and weight were measured.

Weight was recorded using a Digital weighing scale pretested for accuracy (Dr. Trust) with minimal clothes. The length of children up to the age of two years was measured with the child on the horizontal measuring scale (Infantometer). The height of children above 2 years of age was measured by using Stadiometer (Alive Stature-meter). Standing height was measured up to the nearest of 0.1 cm. The child was made to stand against the scale without shoes, heels together and shoulder buttocks and heels touching the vertical surface. Height was recorded with a headpiece touching the top of the head when the child was looking straight and arms naturally hanging by the sides.9,10

Data Analysis

The main outcome variables were stunting and wasting. WHO growth charts for the boys and girls were used for classifying stunting and wasting. The child having a Z score for, height for age less than –2SD was classified as “moderate stunting” and that with a Z score, less than -3SD was classified as “severe stunting”. Similarly, the child with a Z score for weight for height less than -2SD was considered as having moderate wasting and those with a score of less than -3SD was considered as having severe wasting. WHO Anthro tool was used to estimate the Z score. Association of various sociodemographic, environmental and behavioural determinants with stunting and wasting was assessed using the appropriate test of significance.11

RESULTS

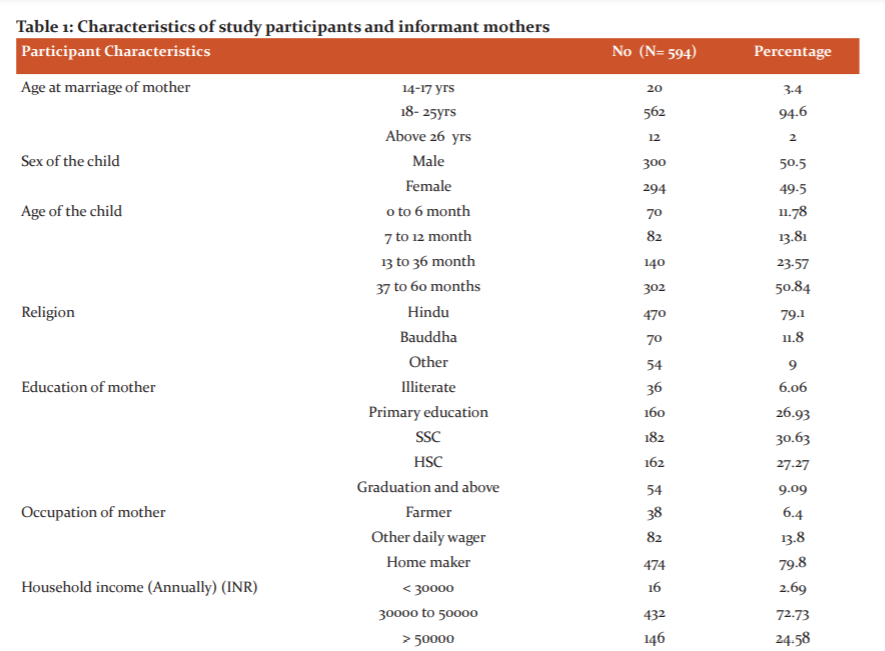

A total of 594 mothers child dyad were included in the study. Nearly 80% were of Hindu Religion and for most of the households (72.73%), annual income was in the range of Rs. 30000 to 50000. The average age of mothers was 29.3 (SD 6.2) years and the majority 94.6% were married at the age between 18 - 25 years, 31% were educated till 10th grade, nearly 80 % homemaker. Out of 120 working women, 6.4% were farm labourer. Among the children in this study, 300 (50.5%) were males, 294 (49.5%) were females. Nearly 99% of children were registered at Anganwadi Centres (AWC). Out of 302 children over 3 years of age, 25% attend AWC regularly and had an attendance of equal to or more than 80%.68 (11.4%) children were going to private playschool or preschool. More detailed characteristics of study participant are given in Table 1.

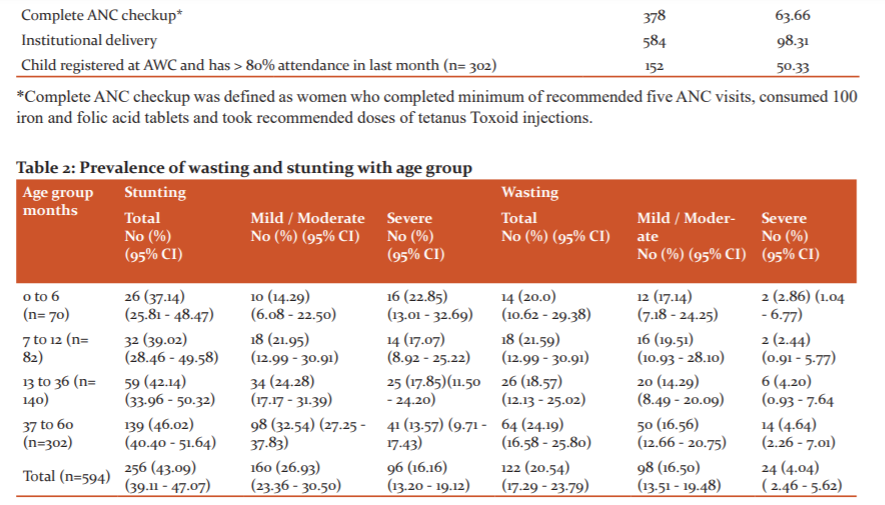

Table 2 reveals that 256 (43.09%) children were stunted and 96 (16.16%) were severely stunted. A total of 122 (20.54%) children were wasted and 24(4.04%) were severely wasted. With regards to age group, nearly 46% in the age group of 3 to 6 years were stunted and 24% were wasted. The proportion of children with severe stunting and wasting were maximum in the age group of 1 to 3 years (Table 2).

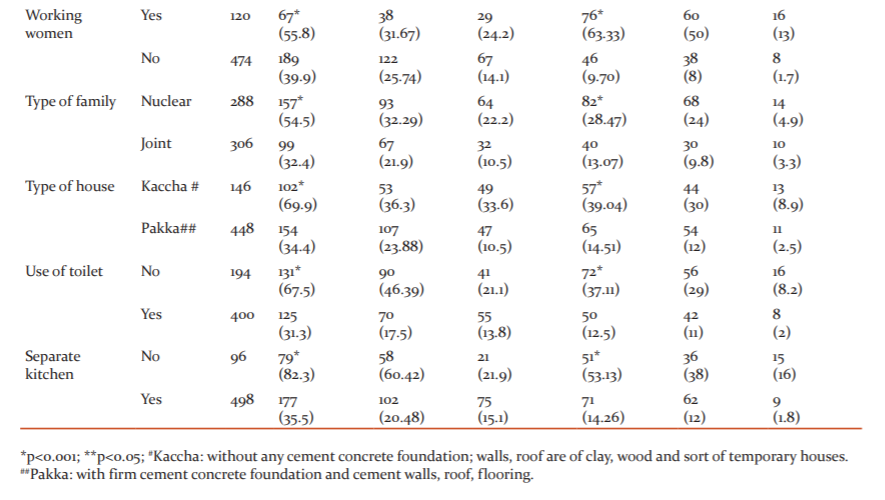

Out of 300 male children, a total of 122 (40.7%) were stunted and 42 (14%) had severe stunting, similarly 59 (19.67%) males children had wasting and 11 (3.7%) had severe wasting. Amongst 294 female children, a total of 134 (45.6%) were stunted and 54 (18.4%) had severe stunting, whereas a total of 63 (21.43%) had wasting and 13 (4.4%) had severe wasting. The proportion of children with stunting and wasting was the highest among the children born to women married early (14-17 years), illiterate women. 193 (41.1%) Children from the Hindu religion were stunted and 97 (20.64%) showed wasting (Table 3).

55.8% of children of working women were stunted compared to 63.3% children of women who were homemaker and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001), similarly wasting was seen more in working women (39.9%) compared to women who are not working for employment (9.7%) and the difference was found to be statistically significant (p<0.001) (Table 3).

Stunting was observed in 54.5% of children from nuclear families compared to 32.4% of children from joint families and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001) and similarly wasting was observed in 28.47% of children from nuclear families compared to 13.07% of children from joint families and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001) (Table 3).

With regards to housing, 69.6% of 146 children living in Kaccha house were stunted compared to 34.4% out of 448 children living in Pakka house and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001). Similarly, the proportion of children with wasting was more in children living in Kaccha house (39%) compared to children living in Pakka house (14.5%) and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Stunting was observed among 67.5% of 194 children from families not using toilets compared to 31.3% of 400 children from families using toilets and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001). Similarly, wasting was observed more in children from families not using toilets (37.11%) compared to 12. 5% of children from families using toilet facilities and the difference were statistically significant (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Stunting was observed in 82.3% of 96 children living in a house not having separate kitchen35.5% of 498 children from houses with separate kitchen and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001). Similarly, wasting was observed more in children from the house not having a separate kitchen (53.13%) compared to 14.26% of children from families not having a separate kitchen and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001) (Table 3).

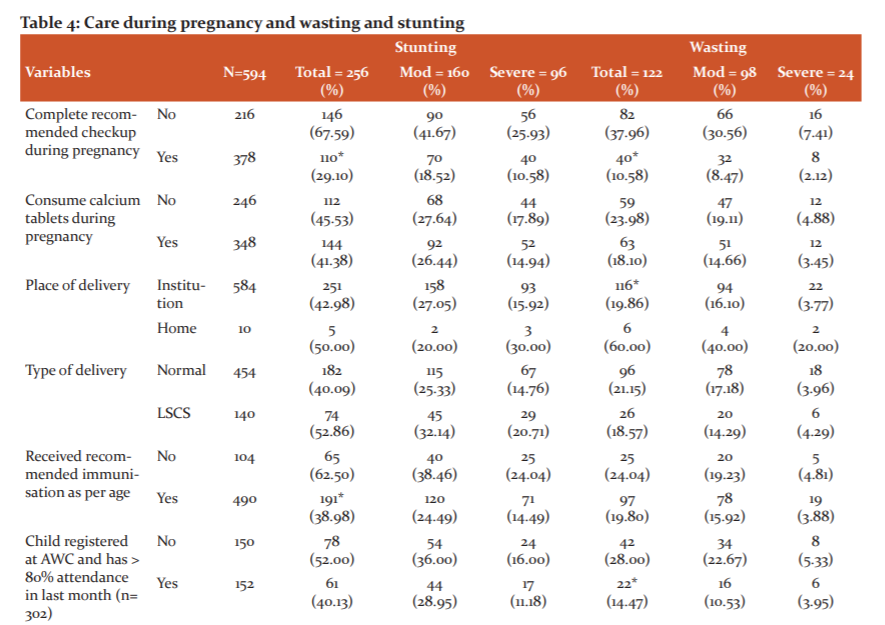

Stunting was observed in 67.6% of children of 216 women who did not receive recommended antenatal care during pregnancy compared to 29.1% children of 378 women who received recommended care and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001). Similarly, wasting was observed in 37.9% children of 216 women who did not receive recommended antenatal care during pregnancy compared to 10.58% children of 378 women who received recommended care and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001) (Table 4). Wasting was observed in 19.86% children of 251 women who had institutional delivery compared to 60% children of 10 women who had home delivery and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001) (Table 4). Total 62.50% of 104 children who did not receive recommended immunization as per age were stunted compared to 38.98% of 490 children who received recommended immunization and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001). Wasting was observed in 28% of 42 children who are not attending the Anganwadi centre regularly compared to 14.47% of 22 children attending the Anganwadi centre regularly and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001) (Table 4).

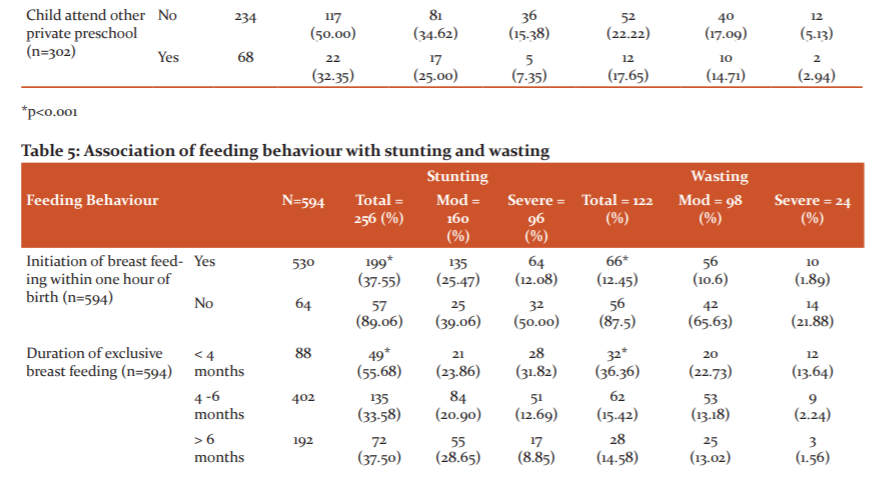

A total of 89.06% of 64 children who did not receive breastfeeding within one hour of birth were stunted compared to 37.55% of 530 children who received and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001). Similarly, the proportion of children with wasting was more in children who not received breastfeeding in one hour of birth (87.5%) compared to 12.45% who not received and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001) (Table 5). Out of the 88 children who received exclusive breastfeeding for less than 4-months, 49 (55.68%) were stunted and 32 (36.36%) were wasted. Prevalence of Wasting reduced as the duration of exclusive breastfeeding increased and was 14.58% among children breastfed for more than 6-months (p<0.001).

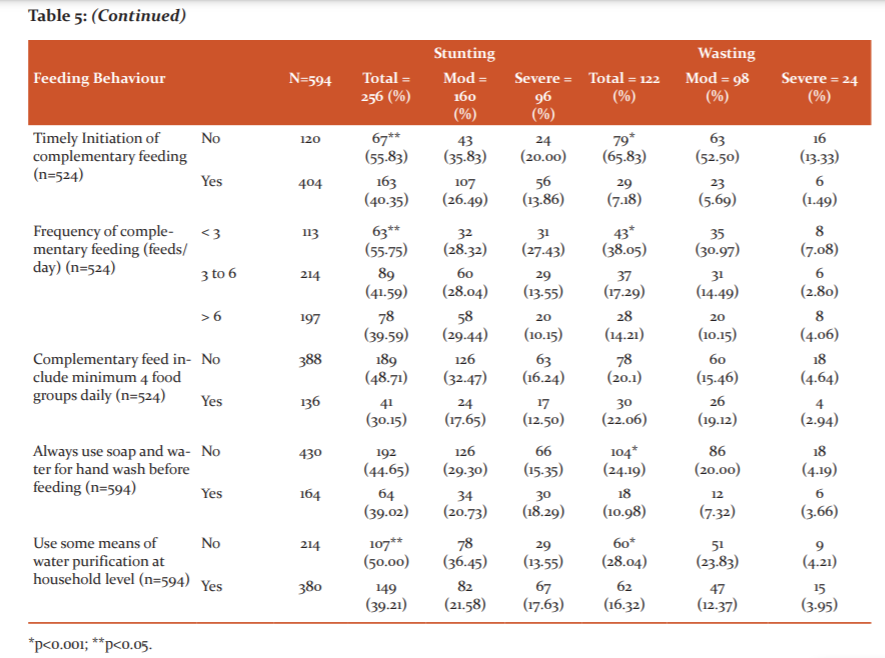

Stunting was observed in 55.83% of 120 children in whom complementary feeding was not initiated timely compared to 40.35% of children in whom it was initiated timely and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.05). The proportion of children with wasting was more in children who were not initiated timely complementary feeding (75.8%) compared to those who received it (7.18%) and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001). Similarly proportion of children with stunting and wasting decreases as the frequency of complementary feeding increases (Table 5).

Wasting was observed in 24.19% of 430 children whose parents do not always use soap and water for handwashing before feeding compared to 10.98% of children whose parents do and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001). Proportion of children with stunting was more among children whose parents do not always wash hands with soap and water before feeding (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Malnutrition was found to be a cause, may be direct or indirect, for 54% of the 10.8 million under-5 deaths per year. Every second death among children under five years in developing countries was attributed to infectious diseases. 11

Prevalence of stunting and wasting

In the present study, the prevalence of stunting was 43.09% and wasting was 20.54%. According to DLHS 4 in Maharashtra, the prevalence of stunting (42%) was almost close to stunting found in this study but was much higher than the prevalence of wasting (6%). 12,13 The reason for the difference in prevalence in the present study and the study conducted by DLHS 4 in Maharashtra was seen because the prevalence by the latter was a complete figure of the whole state whereas our study represents the prevalence of few villages in Maharashtra state. Almost similar findings were reported in the previous studies.14-22

Association of Stunting and wasting with Gender

In the present study stunting in females was somewhat higher than males; 40.7% males & 45.6% females were stunted. Gender was not significantly associated with stunting. Studies of other investigators that revealed similar findings.8,23-25 The rate of stunting was significantly higher in male children.20,26,27 In the present study, 19.67% male & 21.43% female children had wasting which is a little higher in females. Gender was not found to be significantly associated with wasting. Mandal GC et al. found that wasting was higher in boys than girls.

Association of age with stunting and wasting

In the present study in children aged 0- 6 months, 37.14% had stunting and 20.0% were wasted. In the age group of 37-60 months, 46.02% were stunted and 24.19% of children were wasted. It was observed that the prevalence of stunting increased as age increases. Prevalence of stunting was found more among elder children and was highest in the 37-60 months age group. Also more wasting was observed among elder children.23,24 No significant association was found between the age of the child and stunting. Also, No significant association was found between the age of the child and wasting. Similar findings were reported by Sengupta et al.21 and Saxena et al.28 who found that 48-59 months old children had the highest stunting. Sengupta et al.,21 found that the 48-59 months (62.0 %) old children had the highest wasting. In the study reported by Ergin et al.18 and Teshome et al.29 Stunting was especially seen between 12-23 months. The prevalence of wasting was greatest among the age group of 6-24 months and tended to decrease among older children.4

Association of Socioeconomic Status with Stunting and wasting

In the socio-economic classification for children with stunting, the majority 432 (72.73%) of the participants belonged to the income class of Rs. 30000 to Rs. 50000 per annum. Socioeconomic status was not found to be significantly associated with stunting or wasting. Stunting among children from low socioeconomic status increased by at least 42% (p<0.001).30 While more than half of children from households with low socioeconomic status were stunted.

Association of Mother’s Education with stunting and wasting

In the present study very few mothers i.e. 36 (6.06%) were illiterate, 342 were educated up to SSC and 216 were educated up to more than SSC. 61.1% of children born to illiterate mothers were stunted whereas 35.6% of children born to mothers educated above SSC were stunted. More prevalence of stunting was seen among children of illiterate women compared to children of women with higher education.25 Similar results were found for wasting. 66.67% of children born to illiterate mothers and 14.81% of children born to mothers educated above SSC were wasted. Education was significantly associated with stunting (p<0.05). Also, education was significantly associated with wasting (p<0.001). Similarly, Ansari NB et al., in their study observed that mothers with no formal schooling were also significantly associated with stunting.31 The highest proportion of stunted children belonged to illiterate mothers and lowest in mothers with higher education.21

Association of feeding habits with Stunting and wasting

Among 530 children who received breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth, 37.55% were stunted and 12.45% were wasted. Among 64 children who did not receive breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth, 89.06% were stunted and 87.5% were wasted. The difference was statistically significant (p<0.001) for stunting and wasting as well.26,27

Out of the 88 children who received exclusive breastfeeding for less than 4-months, 49 (55.68%) were stunted and 32 (36.36%) were wasted. Prevalence of Wasting reduced as the duration of exclusive breastfeeding increased and was 14.58% among children breastfed for more than 6-months (p<0.001). Duration of Exclusive breastfeeding was significantly associated with stunting (p<0.001) and also with wasting (p<0.001). Conversely, highest prevalence of stunting and wasting was found in those who were exclusively breastfed more than 6 months, followed by those who received exclusive breastfeeding for less than 4 months and lowest for those who were exclusively breastfed for 4-6 months.21

A significant association was found between stunting and timely initiation of complementary feeding (p<0.05). Also, a significant association was found between wasting and timely initiation of complementary feeding (p<0.001). The proportion of children with stunting and wasting decreases as the frequency of complementary feeding increases.29-31 A significant association was found between wasting and parents habit of using soap and water for handwashing before feeding (p<0.001). The proportion of children with stunting was more among children whose parents do not always wash hands with soap and water before feeding. The present study lacks the representativeness of the sample as the study was conducted in one block. The study duration was very small.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

To conclude, the overall study shows that stunting and wasting did not change much across India and Maharashtra. Overall the present study revealed more stunting & fewer wasting cases from the rural area of Wardha district. Health workers need to continue awareness regarding initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour of birth and exclusive Breastfeeding. Motivate other family members to support women for appropriate Infant and Young Child Feeding practices (IYCF). Also, extensive work needs to be done to inhibit the use of feeding bottles and commercial infant food substitutes available in the market. Strict regulatory approaches need to be taken by government machinery to control distracting advertisements of these products.

References:

-

Young ME. From child development to human development. Investing in our children’s future. The world Bank, Washington D.C. 2002:63-78.

-

Renuka M, Rakesh A, Babu NM, Santosh KA. Nutritional 22. status of Jenukuruba preschool children in Mysore district, Karnataka. J Res Med Sci 2011;1:12-7.

-

Farid-ul-Hasnain S, Sophie R. Prevalence and risk factors for Stunting among children under 5 years: a community-based study from Jhangara town, Dadu Sindh. J Pak Med Assoc 2010;60(1):41.

-

Badham J, Sweet L. Stunting: an overview. Sight and Life Magazine. 2010(3/2010):40-7.

-

UNICEF. Key facts and figures on nutrition. https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/

-

Unicef. The state of the world's children 2012: children in an urban world. social sciences; 2012 Mar. https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-worlds-children-2012.

-

Islam S, Goswami Mahanta T, Sharma R, Hiranya S. Nutritional Status of under 5 Children belonging to Tribal Population Living in Riverine (Char) Areas of Dibrugarh District, Assam. Indian J Community Med 2014?39(3):169–74.

-

Mandal GC, Bose K, Bisai S, Ganguli S. Undernutrition among integrated child development services (ICDS) scheme children aged 2-6 years of Arambag, Hooghly district, West Bengal, India: A serious public health problem. Italian J Public Health 2012;16(1).

-

Collins S, Yates R. The need to update the classification of acute malnutrition. Lancet 2003;362(9379):249.

-

UNICEF. Progress for children: a World fit for children: a statistical review. 2007. https://www.unicef.org/reports/progress-children-no-6.

-

Kant L, Gupta A, Mehta SP. Profile of Anganwadi workers and their knowledge about ICDS. Indian J Pediatr 1984;51(4):401-2.

-

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-4), 2013-2014: Maharashtra. Available from-http://www.iipsindia.org/pdf/Directos_Report_2013-2014.pdf

-

Ricci JA, Becker S. Risk factors for wasting and stunting among children in Metro Cebu, Philippines. Am J Clin Nutr 1996;63(6):966-75.

-

Adel ET, Marie-Françoise RC, Salaheddin MM, Najeeb E, Monem Ahmed A, Ibrahim B, et al. Nutritional status of under-five children in Libya; a national population-based survey. Libyan J Med 2008;3(1):13-9.

-

Fawzi WW, Herrera MG, Willett WC, Nestel P, El Amin A, Mohamed KA. The effect of vitamin A supplementation on the growth of preschool children in Sudan. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(8):1359-62.

-

Reyes H, Pérez-Cuevas R, Sandoval A, Castillo R, Santos JI, Doubova SV, et al. The family as a determinant of stunting in children living in conditions of extreme poverty: a case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2004;4(1):57.

-

Nandy S, Irving M, Gordon D, Subramanian SV, Smith GD. Poverty, child undernutrition and morbidity: new evidence from India. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2005;83:210-6.

-

Ergin F, Okyay P, Atasoylu G, Beser E. Nutritional status and risk factors of chronic malnutrition in children under five years of age in Aydin, a western city of Turkey. Turkish J Pediatr 2007;49(3):283.

-

Mittal A, Singh J, Ahluwalia SK. Effect of maternal factors on nutritional status of 1-5-year-old children in urban slum population. Indian J Comm Med 2007;32(4):264.

-

Briend A, Prinzo ZW. Dietary management of moderate malnutrition: time for a change. Food Nutr Bull 2009;30(3_suppl3): S265-6.

-

Sengupta P, Philip N, Benjamin AI. Epidemiological correlates of under-nutrition in under-5 years children in an urban slum of Ludhiana. Health Population Perspect Issues. 2010;33(1):1-9.

-

Dani V, Satav A, Pendharkar J, Ughade S, Jain D, Adhav A, Sadanshiv A. Prevalence of under nutrition in under-five tribal children of Melghat: A community-based cross-sectional study in Central India. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2015;3(2):77-84.

-

Sharif ZM, Ang M. Assessment of food insecurity among low-income households in Kuala Lumpur using the Radimer/Cornell food insecurity instrument–a validation study. Malays J Nutr. 2001;7(1 & 2):15-32.

-

Ejaz MS, Latif N. Stunting and micronutrient deficiencies in malnourished children. JPMA. 2010;60(543).

-

Bhavsar S, Hemant M, Kulkarni R. Maternal and environmental factors affecting the nutritional status of children in Mumbai urban slum. Int J Sci Res Pub. 2012 Nov;2(11):1-9.

-

Zere E, McIntyre D. Inequities in under-five child malnutrition in South Africa. Int J Equity Health 2003;2(1):7.

-

Anand A, Sahoo D. Household and Environmental Conditions Influencing Health and Survival of Children in Northern and Southern Regions of India. IUSSP International Population Conference 2013 At: Busan, Korea.

-

Saxena N, Nayar D, Kapil U. Prevalence of underweight, stunting and wasting. Indian Paediatr 1997;34:627-30.

-

Teshome B, Kogi-Makau W, Getahun Z, Taye G. Magnitude and determinants of stunting in children under five years of age in food surplus region of Ethiopia: the case of west gojam zone. Ethiop J Health Dev 2009;23(2):237-241.

-

Gurmu E, Etana D. Household structure and children’s nutritional status in Ethiopia. Genus. 2013;69(2).

-

Baig-Ansari N, Rahbar MH, Bhutta ZA, Badruddin SH. Child's gender and household food insecurity are associated with stunting among young Pakistani children residing in urban squatter settlements. Food Nutr Bull 2006;27(2):114-27.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License