Welcome to IJCRR

Indexed and Abstracted in: Crossref, CAS Abstracts, Publons, Google Scholar, Open J-Gate, ROAD, Indian Citation Index (ICI), ResearchGATE, Ulrich's Periodicals Directory, WorldCat (World's largest network of library content and services)

PHYTOCHEMISTRY

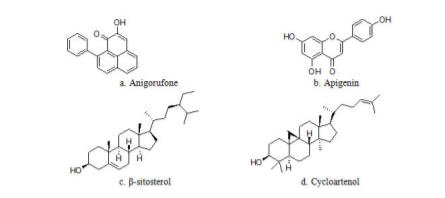

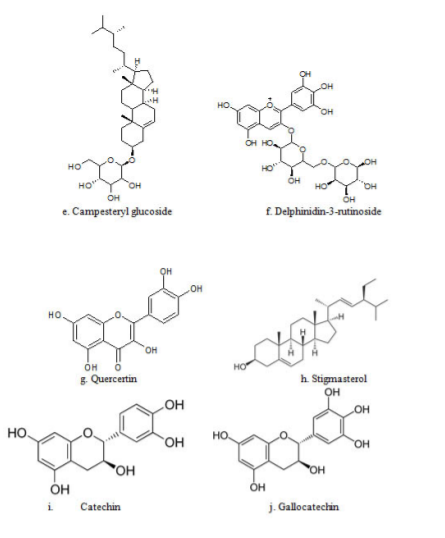

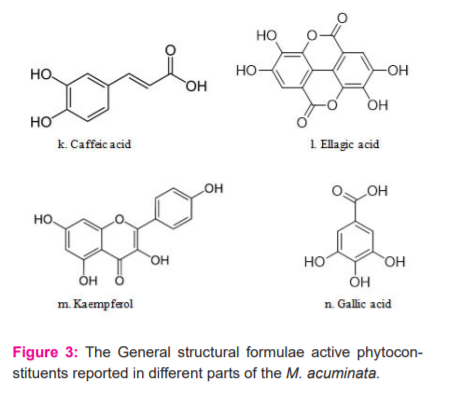

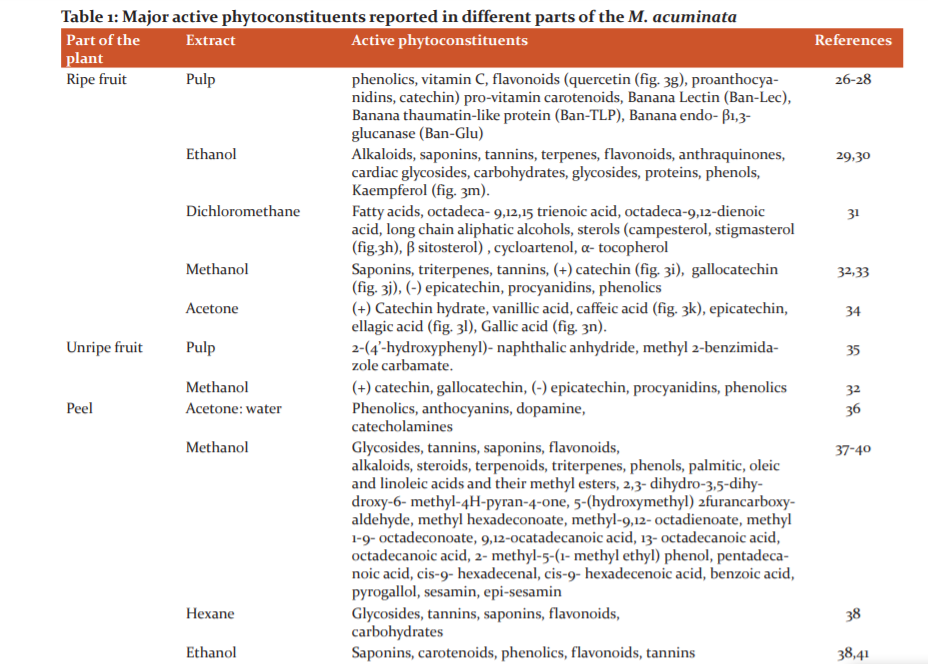

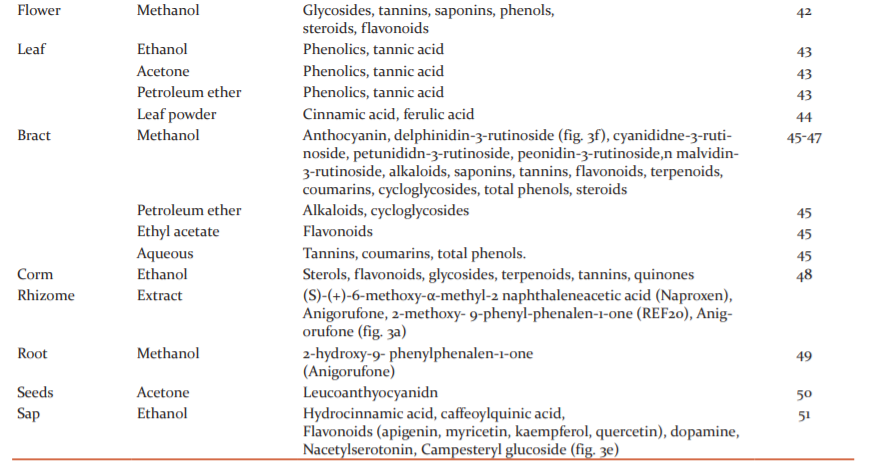

The phytochemical analysis of different parts of Musa acuminata such as fruit, peel, flower, leaf, pseudostem, and rhizome has shown the presence of a rich diversity of phytochemicals like saponins, terpenoids, steroids, anthocyanins, fatty acids, tannins, phenols, and alkaloids. Phytochemicals content is reported to vary with the extraction method employed, and compounds identified in various plant parts of Musa acuminata are presented in Table 1.24 Plants continue to be an important source of bioactive compounds and involve a multidisciplinary approach combining ethnobotanical, phytochemical, and biological techniques to provide new chemical compounds. The presence of bioactive compounds like apigenin glycosides, myricetin glycoside, myricetin-3-O-rutinoside, naringenin glycosides, kaempferol-3-Orutinoside, dopamine, N-acetyl serotonin, and rutin, has been reported in different species of Musa.25 The detailed structural presentations are reported in figure 3.

NUTRITIVE VALUE

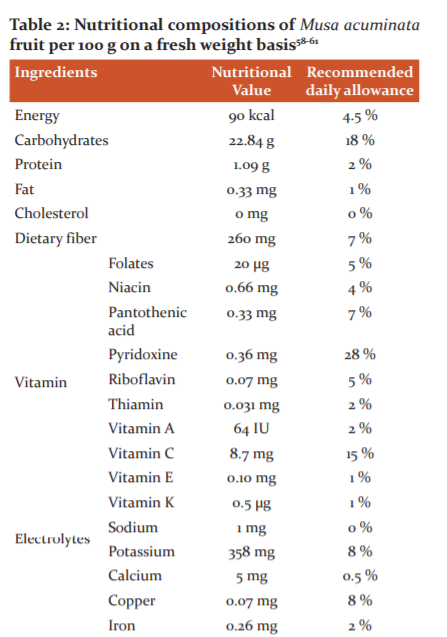

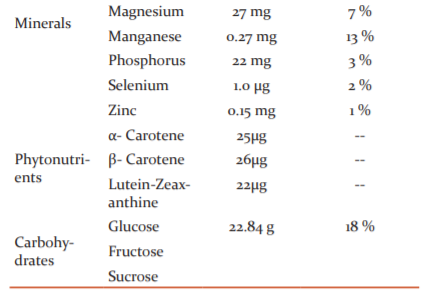

Banana, tropical fruit with high calorie, provides exceptional nutrition in different forms. Banana, tropical fruit with high calorie, provides exceptional nutrition in different forms. Musa family contains starch, fructans, phenolic acid, anthocyanins, terpenoids, and sterols. In unripe plantains, starch is present over 80% of the dry weight of the pulp. The fat content of plantains and bananas are very less about 0.5% and so fats do not contribute much to the energy content.52 The total protein value of plantain is related to dry weight is more than 3.5% in ripe pulp and it is slightly less in fresh fruit. About 1.3% of sugars are present in total dry matter in unripe plantains, but this rise to around 17% in the ripe fruit. It is an excellent source of some vitamins like carotene (vitamin A), Thiamine (vitamin B1), riboflavin (vitamin B2), niacin (vitamin B3), pyridoxine (vitamin B6) and ascorbic acid (vitamin C). Pyridoxine is an important B-complex vitamin that plays a vital role in the treatment and management of neuritis and anaemia. Moreover, it helps to decrease homocysteine one of the causative factors in coronary artery disease CHD and stroke episodes level inside the body.53 Potassium, an important component of cell and body fluids, supports muscles and nerves. Banana is rich in starch and it is a rich source of potassium. Potassium benefits the muscles as it helps maintain their proper working and prevents muscle spasms. Also, recent studies are showing that potassium can help to decrease blood pressure in individuals who are potassium deficient. Potassium also reduces the risk of stroke. In addition to manganese, magnesium is essential elements for strong bone and has a cardiac active role. Manganese is used as a co-factor in the body for the enzyme, superoxide dismutase oxidation. Copper is playing an important role in the production of RBCs. Banana is rich in fructose and sucrose. It replenishes energy and revitalizes the body instantly. It is a moderate source of health-promoting flavonoid and poly-phenolic antioxidants such as lutein and zeaxanthin. It contains β- and α-carotenes in small quantities. These compounds help act as protective scavengers and neutralize oxygen-derived free radicals and reactive oxygen species ROS.54 Banana is rich in fatty acids, phytosterols, and steryl glucosides Steryl esters and free sterols such as campesterol, β-sitosterol (Figure 3c), cycloartenol (Figure 3d), and stigmasterol (Figure 3h) are the major lipophilic component found in the unripe banana peel.55 Steryl esters and free sterols are the major lipophilic component found in unripe banana peel, while free fatty acids and sterols dominate banana pulp. Banana fruits contain a major quantity of essential mineral elements and could serve as a source of minerals in human and animal daily routine diets.56,57 Detail description of the nutritional importance of Musa acuminata is described in Table 2.

PHARMACOLOGICAL ACTIVITIES

Different parts of the Musa acuminata plant have shown potential for disease prevention in traditional medicine, which may be attributed to the rich and diversified content of phytochemicals present in them. Various models were used to investigate the health-promoting properties of M. acuminata, and description of available in-vitro and in-vivo models are detailed here.

Blood cholesterol-lowering property

The antioxidants property of kepok banana peel is due to the presence of saponin, tannin, and flavonoid and responsible for the decrease in the blood total cholesterol level. The current study determines whether saponin, tannin, and flavonoid in kepok banana peels are effective against total blood cholesterol levels in obese mice. This experiment using 20 obese male mice Mus musculus L. strain Deutschland-Denken-Yoken and divided into four groups, which are normal control group, obese control group, and groups that were given an extract of Kepok Banana Peel Musa acuminata treatment with dose 8,4 mg/day and 16,8 mg/day. The treatment was given in 14 days. The total cholesterol level of each group was measured by spectrophotometer. The results obtained p=0,000, in a one-way ANOVA test. Furthermore, the Post Hoc Test generally found that there were significant differences between groups. There is an effect of giving kepok banana peel to decrease the total cholesterol level of obese mice. The effect of kapok Banana peel extract level of 8.4 mg/day remarkably decreases total blood cholesterol level compared to banana peel extract level of 16.8 mg/day. The anti-cholesterol effect of banana fibre ethanol extract proved to a significant decrease in total cholesterol in obese male mice Mus musculus L. strain Deutschland-Denken-Yoken. 62

Antioxidative properties

Banana fruits Musa acuminata Juss. are important foods, but there have been very few studies evaluating the phenolics associated with their cell walls. In the present study, + catechin, gallocatechin, and − epicatechin, as well as condensed tannins, were detected in the soluble extract of the fruit pulp; neither soluble anthocyanidins nor anthocyanins were present. In the soluble cell wall fraction, two hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives were predominant, whereas in the insoluble cell wall fraction, the anthocyanidin delphinidin, which is reported in banana cell walls for the first time, was predominant. Cell wall fractions showed remarkable antioxidant capacity, especially after acid and enzymatic hydrolysis, which was correlated with the total phenolic content released after the hydrolysis of the water-insoluble polymer, but not for the post hydrolysis water-soluble polymer. The acid hydrolysis released various monosaccharides, whereas enzymatic hydrolysis released one peak of oligosaccharides. These results indicate that banana cell walls could be a suitable source of natural antioxidants and that they could be bioaccessible in the human gut.63

Plant?based natural remedies remain the treatment of choice as they are deemed effective, safe, and with minimal adverse side effects. the Natural Products Discovery Laboratory at the Institute of Bio?IT Selangor, Universiti Selangor, Malaysia carried out studies on the hepatoprotective, antiulcerogenic, antioxidant, and cytotoxic activities of Musa acuminata. The results showed that under certain conditions, the methanolic extracts of unripe Musa acuminata showed equivalent activity to the commercial hepatoprotective drug silymarin and anti?ulcer drug omeprazole as demonstrated in the animal model. The extracts were not cytotoxic and exhibited low to moderate antioxidant activity. These ameliorative effects could be related to the saponins, flavonoids, and triterpenes in the peel and pulp extracts, and the tannins present in the peel extract. Further investigations are required to optimize the extraction of bioactive compounds that work synergistically to produce the ameliorative or protective effects described in our studies.64

Anticancer activity

The total phenols and flavonoids, anticancer and antioxidant activities ethanol extracts of three plants Phoenix dactylifera, Musa acuminata, and Cucurbita maxima were determined. The total phenolic contents were computed to be 342 µg/mL gallic acid equivalents in ethanol extract of banana fruit while the highest total flavonoids were in ethanol extract of molasses date 1424 µM as rutin equivalent. In vitro anticancer activity was determined using EACC and HeLa cell lines. In vitro anticancer activity against EACC revealed that the maximum inhibition was observed in ethanol extract of pumpkin seeds 100% at 100µg/ml while the maximum inhibition against the HeLa cell line was observed in ethanol extract of date seeds 90% at 100µg/ml. The antioxidant activity was determined using three different methods DPPH, ABTS scavenging activity, and reducing power. DPPH scavenging activity was found to be 85 and 84 % in ethanol extracts of date seed and banana fruit, respectively. ABTS scavenging activity was found to be 98, 98, 95, and 95 % in ethanol extracts of seeds, molasses of date, fruit, and peel of a banana, respectively. The reducing power was 873, 833, and 871 µg/mL GAE in the ethanol extracts of molasses, seeds, and fruit of date. Four different formulas were prepared from tested plants and the sensory evaluation of these formulas showed that prepared formulas were judged as highly accepted. The results showed that ethanol extracts of date parts, banana peel pumpkin seeds are promising new antioxidant and anticancer agents and prepared formulas could be used as a daily health supplement.65

Another study was performed to evaluate the radioprotective and anticancer effect of banana peels extract on male mice. Sixty male mice weighed 18- were used, the animals divided equally into six groups as follow first group act as normal, second group Tumor control implanted with Ehrlich tumour, third group, the irradiated group exposed to a single dose of 3.0 GY of gamma rays, fourth group banana peels extract 300 mg/kg/day orally for 3weeks, fifth group tumour implanted + banana peels extract 300 mg/kg/day orally for 3weeks, sixth group irradiated with dose 3.0 GY gamma+ 300 mg/kg/day for 3 weeks. At the end of the experimental mice were sacrificed by anaesthesia and the blood was collected to evaluate biochemical parameters Complete Blood Count, Carcinoembryonic antigen, Malonaldehyde, Molecular study, electrophoretic assayed. The results showed that banana peels extract ameliorate the alteration in irradiated and tumour group, and significantly decrease p≤0.05 the elevation of Carcinoembryonic antigen in tumour implanted group, significantly decrease the elevation of Malonaldehyde in tumor implanted group and irradiated group. According to protein fractions and western blotting data, it could be concluded that addition banana peels extract consider a crucial impact for Irradiation dose which is cleared through a huge increase of Polymorphism % for addition banana peels extract 20% comparing with to Irradiation treatment which didn’t reflect polymorphism. Furthermore, noticeable stimulation for P53 expression level was detected for applying banana peels extract and Irradiation as a Compound dosage.66

Inhibitory Activity

Musa species is a traditional Indian medicinal plant used for the management and treatment of many diseases. The current study was compared the anticholinesterase, anti?inflammatory, antioxidant, and antidiabetic activities of Musa acuminata Simili rajah, ABB fruits and leaves fractions followed by characterization of the phytoconstituents using HPTLC?HRMS and NMR. Leaf fractions exhibit a remarkable pharmacological activity than the fruit. Ethyl acetate fraction of the leaf contains a major concentration of total phenolic content 911.9 ± 1.7 mg GAE/g and gives significant DPPH· scavenging activity with IC50, 9.0 ± 0.4 µg/ml. It also exhibits the remarkable inhibition of acetylcholinesterase IC50, 404.4 ± 8.0 µg/ml and α?glucosidase IC50, 4.9 ± 1.6 µg/ml, but a moderate α?amylase inhibition IC50, 444.3 ± 4.0 µg/ml. The anti?inflammatory activity of n?butanol IC50, 34.1 ± 2.6 µg/ml and ethyl acetate fractions IC50, 43.1 ± 11.3 µg/ml of the leaf were higher than the positive control, quercetin IC50, 54.8 ± 17.1 µg/ml. Kaempferol?3?O?rutinoside and quercetin?3?O?rutinoside rutin were identified as the novel medicinal agent with potent antioxidant and antidiabetic activities from the ethyl acetate fraction of Musa acuminata leaf.67

Immunomodulatory activity

To explore the feasibility of Musa acuminata banana peels as a feed additive, the effects of banana peel flour BPF on the growth and immune functions of Labeo rohita were evaluated. Diets containing five different concentrations of BPF 0% basal diet, 1% B1, 3% B3, 5% B5, and 7% B7 were fed to the fish average weight: 15.3 g for 60 days. The final weight gain and specific growth rate were higher in the B5 group. The most significant improvements in immune parameters such as lysozyme, alternative complement pathway, leukocyte phagocytic, superoxide dismutase, and catalase activities were observed in the B5 group. However, the B5 group exhibited the lowest malondialdehyde activity. IgM and glutathione peroxidase activities were significantly elevated in the treatment groups, except in B1, after only 30 days of feeding. Of the examined cytokine-related genes, IL-1β, TNF-α, and HSP70 were upregulated in the head kidney and hepatopancreas, and expressions were generally higher in the B3 and B5 groups. Moreover, the B5 group challenged with Aeromonas hydrophila 60 days after feeding exhibited the highest survival rate of 70%. These results suggest that dietary BPF at 5% could promote growth performance and strengthen immunity in L. rohita.68

Wound healing activity

Banana Musa acuminata peel is a rich source of many nutrients and is considered high in carbohydrates. It has been traditionally used to treat diarrhoea, anaemia, and ulcers. Some studies have shown that banana peels possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. This study was performed to evaluate the wound healing activity of banana peels extract BPE in the rabbit. For inducing full-thickness wound in rabbits, the excisional wound model was used. The animals were randomly divided into six experimental groups. Negative control, standard and vehicle control groups, and treatment groups. All the treatment was applied topically twice daily. Healing was assessed by wound contraction and re-epithelialization rate and the tensile strength of the wound tissue sample. Histopathological studies also showed the wound healing activity of BPE. The results of this study indicated that the hydroalcoholic extract of banana peels has a strong potential for wound healing and it can be used for different types of wounds in human beings to.69

Antibacterial activity

An in vitro test was carried out to assess qualitatively the antibacterial activity of the Musa acuminata leaf methanol extract coated sample against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538, a gram-positive microorganism, and Escherichia coli, a gram-negative microorganism, using nutrient agar, purchased from M/s T. Stanes & Company Limited, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu. Nutrient agar plates were prepared by pouring 15 ml of nutrient agar medium into sterile Petri dishes. The dishes were allowed to solidify for 5 min, and 0.1% inoculum suspension was smeared uniformly and the inoculum was left to dry for 5 min. The Musa acuminata leaf methanol extract-finished fabric of 2.0 cm diameter was placed on the surface of the medium, and the plates were incubated at 37.5°C for 24 h AATCC Technical Manual, 2007. After completion of incubation, the fabric sample was taken out and the zone of inhibition formed in the fabric was measured in millimetres and the readings were recorded.70

The ethanolic 96%, acetone and petroleum ether extracts of Musa acuminata leaf showed excellent antifungal activities against two pathogenic fungi Aspergillus terreus and Penicillium solitum with up to 5.7 cm inhibition zone diameter at 20 mg/mL of the extract. 71 A formulated gel preparation containing 4% Musa acuminata leaf acetone extract was reported to show an inhibition zone diameter of 27 mm against C. albicans, which was comparable to Nystatin cream used as control.72

Antidiabetic activity

In an investigation the antihyperglycemic effect of ethanolic extract of inner peels of Musa acuminata fruit 100- 400 mg/Kg p.o. along with control 1% gum acacia, 1 mL/Kg p.o. and standard drug Glimepiride, 0.09 mg/Kg p.o. using oral glucose tolerance test in normoglycemic Wistar rats. The extract-treated group showed a dose-dependent antihyperglycemic effect, but no significant p<0.05 change in blood glucose levels was observed among control, extract-treated and drug-treated groups in normoglycemic rats; however, extracts at 200 and 400 mg kg p.o. level showed a significant decrease in p<0.01 in the blood glucose levels in glucose loaded normoglycemic rats, which was almost similar to the standard drug. These observations validate the use of Musa acuminata fruits for diabetic patients in the traditional practice in Mauritius, and other plant parts for the control of diabetes in India and Bangladesh.73

Leishmanicidal activity

A study found that the leishmanicidal activity of phytoalexins from M. acuminata. The antifungal phenyl-phenalenone phytoalexin REF20 and Anigorufone compounds from the rhizomes of Musa acuminate was target the mitochondria of Leishmania donovani Promastigotes and Leishmania infantum Amastigotes. The REF20 had a slightly better inhibitory effect on proliferation of L. donovani and L. infantum LC50 of 10.3 and 10.5 μg/mL than the Anigorufone LC50 of 12.0 and 13.3 μg/mL. The extracts also inhibited the mitochondrial fractions with a reduction in succinate dehydrogenase activity SDH and fumarate reductase FRD activity. The REF20 showed higher EC50 value 59.6 μg/mL for SDH than Anigorufone 33.5 μg/mL; however, FRD 47.8 and 53.1 μg/mL and purified-FRD 77.2 and 89.0 μg/mL values were lower for REF20 than Anigorufone. These results indicate that the phenylphenalenone phytoalexins have the potential to be used as a new structural motif for leishmanicidal activity, and they can be used for the development of leishmanicidal drugs.74

Toxicology

The available information regarding the uses of Musa acuminata fruit and other parts by local and tribal people suggests that it is non-toxic. Although not very popular, fruit and other plant part are consumed by tribal populations throughout the world. The Musa acuminata blossom is a popular Sri Lankan dish consumed as a curry, boiled, or used as a deep-fried salad for ages.75 The animal models used in various studies have concluded that there were no adverse effects from the administration of Musa acuminata extracts.76-79 The flowering stalk of Musa acuminata was found to be non-toxic to the murine monocytic macrophages cell line.80 and brine shrimp toxicity test performed on Artemia salina showed that Musa acuminata flower extract was not toxic as it showed the LC50 value of 9.97 mg/mL, which was much above the cut-off point of toxicity level of 1.0 mg/mL.81 The use of Musa acuminata peel as a major ingredient in food products suggests that it is considered safe for consumption.82,83 Additionally, the National Cancer Standard Institute declared that the banana peel is non-toxic to human cells.84

Conclusion and future Perspectives

All the available information on Musa acuminata was collected via electronic search using Pubmed, Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, J-Gate, Google Scholar, and a library search for articles published in peer-reviewed journals, local magazines, unpublished materials, theses, and ethnobotanical textbooks were done. The Plant List www.theplantlist.org, Promusa www.promusa.org, Musalit www.musalit.org, and the Integrated Taxonomic Information System ITIS www.itis.gov name databases were used to validate the scientific names and also provide information on the subspecies and cultivars of M. acuminata. This review thus may provide the scientific basis for future research work on Musa acuminata for the development of phytomedicines as well as edible products with functional properties. The proximate analysis of Musa acuminata fruits reveals that its contents can contribute to the recommended daily requirements of Vitamin C and minerals such as Potassium and Magnesium, and it can be used as an ingredient in functional foods. The rich diversity of phytochemicals present in Musa acuminata plant parts may be responsible for health beneficial effects and justify their use against various diseases in traditional medicine. Some studies on animal models against selected pathological conditions provide evidence of the efficacy of the Musa acuminata plant as a therapeutic agent and acclaim the use of Musa acuminata by various tribes and ethnic groups across the geographical boundaries of the world. Musa acuminata plant parts have been consumed in varying quantities and forms by many populations across the globe over a long period, and no toxicity has been reported. However, the major edible part of M. acuminata; the fruits, which provides energy, vitamins, and minerals in good amounts are rarely consumed; and food application of other plant parts also is still unknown, which opens the door for the development of food products with potential health benefits from M. acuminata.

Musa acuminata has been traditionally used to treat various diseases and ailments such as fever, bronchitis, allergic reactions, sexually transmitted infections, and some non-communicable diseases. All parts of the plant including fruit, stem, pseudostem, flower, leaf, sap, inner trunk, inner core, and root have found their use in traditional medicine. The compounds isolated from

Musa acuminata have been used as anti-hypertensive, anti-diabetic, anthelmintic, and anti-HIV; and have proven useful against tuberculosis and other respiratory diseases traditionally. Musa acuminata has been used in antimicrobial gel formulations, and the curative effect of Musa acuminata in combination with western medicine has been shown in a clinical study, however, the potential of some of the parts of this plant in disease prevention is not known, which needs further study. There are promising phytochemicals present in M. acuminata, such as S-+-6- methoxy-α-methyl-2-naphthaleneacetic acid anti-inflammatory activity, BanLec anti-HIV-1 activity, and others that show promising wound healing, anti-tuberculosis and Leishmanicidal activity, which needs to be taken to clinical trials for the possible development of drugs. Another bioactive constituent s of Musa acuminata also need further investigations for validation of various pharmacological claims, and to explore their potential use in the development of drugs and as a functional food ingredient. Investigations are also required to characterize various phytochemicals present in Musa acuminata that work individually or synergistically with other compounds or known drugs to provide the ameliorative or protective effects against various diseases.

ABBREVIATIONS

ABTS, 2,2'-azino-bis3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid; CHD, Coronary artery disease; DPPH, 2?diphenyl?1?picrylhydrazyl; FRD, fumarate reductase; ITIS, Integrated Taxonomic Information System; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; SDH, Succinate dehydrogenase; WHO, The World Health Organization.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE: Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS: No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: Nil

ACKNOWLEDGMENT: The authors are thankful to CSIR-National Botanical Research Institute, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India for providing the library facilities to the compilation of the current review. The authors are also grateful to publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed.

References:

Ji H, Li X, Zhang H, Natural products and drug discovery. Can thousands of years of ancient medical knowledge lead us to new and powerful drug combinations in the fight against cancer and dementia? EMBO Rep 2009;10:194–200.

Kamboj VP. Herbal medicine. Curr Sci. 2000;78:35-9.

Zhang P, Whistler R, Bemiller J, Hamaker B, Banana starch: Production, physicochemical properties, and digestibility-a review. Carbohydr Polym 2005; 59:443–58.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musa_acuminata. (Accesses on 12/05/2020).

Musa acuminata Colla, 1820. Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), 2011.

D’Hont A, Denoeud F, Aury J, Baurens, F Carreel F, Garsmeur O, et al. The 57 banana (Musa acuminata) genome and the evolution of monocotyledonous plants. Nature 2012;488: 213–17.

Simmonds NW. Evolution of the bananas. 1962. Longman, London.

Simmonds NW, Shepherd K. The taxonomy and origins of cultivated bananas. Bot J Linn Soc 1955;55:302–12.

Daniells JW, Jenny C, Karamura DA, Tomekpe K, Arnaud E, Sharrock S.. Musalogue: a catalogue of Musa germplasm diversity in the genus Musa. International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plantain (INIBAP), France. 2001.

Wong C, Kiew R, Loh JP, Gan L.H, Ohn S, Lee SK, et al. Genetic diversity of the wild Banana Musa acuminata Colla in Malayisa as evidenced by AFLP Ann Bot 2001;88:1017–25.

Simmonds NW. 1962. Evolution of the bananas. Longman, London.

Chakravorti AK. A preliminary note on the occurrence of the genus Musa L. in India and the features in its distribution. J Indian Bot Soc. 1948;27:84- 90.

Chandraratna MF. The origin of cultivated races of banana. Indian J Gen 1951;11:29-3.

Dutta S, Some bananas of Assam. Ind J Hort 1952;9: 26-35.

Singh DB, Sreekumar PV, Sharma TVRS, Bandyopadhyay K. Musa balbisiana var. andamanica (Musaceae) – A new banana variety from Andaman Islands. Malayan Nat J 1998;52:157-60.

Singh DB, Suryanarayana MA. In Andamans cultivating bananas scientifically. Ind Hort 1997;2:30-2.

Uma S, Selvarajan R. Collection and characterisation of banana and plantains of northeastern India. In: Molina, A.B, Roa, V.N., Maghuyop, M.A.G., (Eds.), Advancing Banana and Plantain R & D in Asia and Pacific. Proceedings of the 10th INIBAP-ASPNET Regional Advisory Committee meeting. 2001. Bangkok, Thailand.

Venkataramani KS. On the occurrence of Musa balbisiana. Madras Agric J 1949;36:552-54.

Subbaraya U. Farmers’ knowledge of wild Musa in India. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States. Rome. 2006.

The wealth of India (1962). Volume VI (L-M). 449.

Radha, T, Mathew L. Fruit crops. Horticulture Science Series. New Indian Publishing Agency 2007;3:33-59.

Seymour G.B. Banana. In: Seymour G.B., Taylor J.E., Tucker G.A. (eds) Biochemistry of Fruit Ripening. Springer, Dordrecht. 1993.

Maduwanthi SDT, Marapana RAUJ. Induced Ripening Agents and Their Effect on Fruit Quality of Banana. Int J Food Sci 2019;10:1-8.

Jiwan SS, Tasleem AZ, Bioactive compounds in banana fruits and their health benefits. Food Quality Safety 2018; 2(4):183–88,

Pothavorn P, Kitdamrongsont K, Swangpol S, Wongniam S, Atawongsa K, Svasti J, et al. Sap phytochemical compositions of some bananas in Thailand. J Agr Food Chem 2010;58:8782-87.

Choudhury SR, Roy S, Sengupta DN. A Ser/Thr protein kinase phosphorylates MAACS1 (Musa acuminata 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase 1) during banana fruit ripening. Planta 2012;236:491–11.

Mahouachi J, López-Climent MF, Gómez-Cadenas A. Hormonal and Hydroxycinnamic acids profiles in banana leaves in response to various periods of water stress. Sci World J 2014;16:1-9.

Onyema CT, Ofor CE, Okudo VC, Ogbuagu AS. Phytochemical and antimicrobial analysis of banana pseudo stem (Musa acuminata). Br J Pharm Res 2016;10:1-9.

Philip DC, Lavanya B, Sasirekha GV, Santhi M. Phytochemical Screening, Antioxidant and antidiabetic activity of Musa acuminata, Citrus sinensis and Phyllanthus emblica. Am J Pharm Tech Res 2015;5:557-64.

Okon, JE, Esenowo GJ, Afaha IP, Umoh NS, Haematopoietic properties of ethanolic fruit extract of Musa acuminata on albino rats. Bull Environ Pharmacol Life Sci 2013;2:22-6.

Vilela C, Santos SAO, Villaverde JJ, Oliveira L, Nunes A, Cordeiro N, et al, Lipophilic phytochemicals from banana fruits of several Musa species. Food Chem 2014;162:247–52.

Bennett RN, Shiga TM, Hassimotto NMA, Rosa EAS, Lajolo FM, Cordenunsi BR. Phenolics and antioxidant properties of fruit pulp and cell wall fractions of postharvest banana (Musa acuminata Juss.) cultivars. J Agric Food Chem 2010;58: 7991–003.

Swanson MD, Winter HC, Goldstein IJ, Markovitz DM. A lectin isolated from bananas is a potent inhibitor of HIV replication. J Biol Chem 2010;285:8646–655.

Islam MR, Afrin S, Khan TA, Howlader ZH. Nutrient content and antioxidant properties of some popular fruits in Bangladesh. Int J Pharm Sci Res 2015;6:1407-414.

Hirai N, Ishida H, Koshmzu K. A phenomenon-type phytoalexin from Musa acuminata. Phytochem 1994;37: 383-85.

Gonzalez-Montelongo R, Lobo MG, Gonzalez M. Antioxidant activity in banana peel extracts: Testing extraction conditions and related bioactive compounds. Food Chem 2010;119:1030–39.

Abdullah FC, Rahimi L, Zakaria ZA, Ibrahim AL.. Hepatoprotective, antiulcerogenic, cytotoxic and antioxidant activities of Musa acuminata peel and pulp. In: Gurib-Fakim, A. (Ed.), Novel Plant Bioresources: Applications in Food, Medicine and Cosmetics John Wiley & Sons, UK. 2014.

Gonzalez-Montelongo R, Lobo MG, Gonzalez M. Antioxidant activity in banana peel extracts: Testing extraction conditions and related bioactive compounds. Food Chem 2010;119:1030–39.

Mordi RC, Fadiaro AE, Owoeye TF, Olanrewaju IO, Uzoamaka GC, Olorunshola SJ. Identification by GC-MS of the components of oils of banana peels extract, phytochemical and antimicrobial analyses. Res J Phytochem 2016;10:39-4.

Niamah AK. Determination, identification of bioactive compounds extracts from yellow banana peels and used in vitro as antimicrobial. Int J Phytomed 2014;6:625-32.

Anal AK, Jaisanti S, Noomhorm A. Enhanced yield of phenolic extracts from banana peels (Musa acuminata Colla AAA) and cinnamon barks (Cinnamomum varum) and their antioxidative potentials in fish oil. J Food Sci Tech 2014;51:2632–639.

Sumathy V, Lachumy SJ, Zakaria Z, Sasidharan S, In-vitro bioactivity and phytochemical screening of Musa acuminata flower. Pharmacology 2011;2:118-27.

Meenashree B, Vasanthi VJ, Mary RNI, Evaluation of total phenolic content and antimicrobial activities exhibited by the leaf extracts of Musa acuminata (banana). Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 2014;3:136-41.

Sembdner G, Parthier B. The biochemistry and the physiological and molecular actions of jasmonates. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 1993;44:569–89.

Gunavathy N, Padmavathy S, Murugavel SC. Phytochemical evaluation of Musa acuminata bract using screening, FTIR and UV-Vis spectroscopic analysis. J Int Academ Res Multidisci Sci 2014;2:212-21.

Kitdamrongsont K, Pothavorn P, Swangpol S, Wongniam S, Atawongsa K, Svasti J, et al, Anthocyanin composition of wild bananas in Thailand. J Agric Food Chem 2008;56:10853–857.

Roobha JJ, Saravanakumar M, Aravindhan KM, Suganyadevi P. In-vitro evaluation of anticancer property of anthocyanin extract from Musa acuminata bract. Res Pharm 2011; 1:17-21.

Venkatesh KV, Kumar GK, Pradeepa K, Kumar SSR. Antibacterial activity of ethanol extract of Musa paradisiaca cv. Puttabale and Musa acuminata cv. Grand naine . Asian J Pharma Clin Res 2013;6:168-72.

Binks RH, Greenham JR, Luis JG, Gowen SR. A Phytoalexin from roots of Musa acuminata var. pisang sipulu. Phytochemistry 1997;45:47-9.

Chandhu JS, Seshadri TR. Isolation of a new leucoanthocyanidin from banana seeds of Musa acuminata Colla. Curr Sci 1962;21:235-36.

Pothavorn P, Kitdamrongsont K, Swangpol S, Wongniam S, Atawongsa K, Svasti J, et al, Sap phytochemical compositions of some bananas in Thailand. J Agric Food Chem 2010; 58:8782–787.

Oliveira L, Freire CSR, Silvestre AJD, Cordeiro N, Lipophilic extracts from banana fruit residues: A source of valuable phytosterols. J Agr Food Chem 2008;56:9520–524.

Hardisson A, Rubio C, Baez A, Marti, M, Alvarez R, Diaz E, Mineral composition of the banana (Musa acuminata) from the island of Tenerife. Food Chem 2001;73(2):153–61.

Nataraj L, Antioxidant capacity and phenolic content of different solvent extract Musa paradisiacal and mustai (Rivea hypocrateriformis). Food Sci Biotech 2010;9(5):1251-258.

Hettiaratchi UP, Chemical compositions and glycemic responses to banana varieties. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2011;62(4):307?309.

Morton J. Banana from Fruits of Warm Climates. Hort Purdue Edu 2009;12:04-15.

Madava Rao VN. Banana. Published by Publication and information division ICAR (Indian Council for Agricultural Research): 8-16.

Menezes EW, Tadini CC, Tribes TB, Zuleta A, Binaghi J, Pak N, et al, Chemical composition and nutritional value of unripe banana flour (Musa acuminata, var. Nanicão). Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2011;66(3):231-37.

Pieltain MC, Castan JIR, Ventura MR, Flores MP, Nutritive value of banana (Musa acuminata L.) fruits for ruminants. Animal Feed Scid Tech 2018;73:187-91.

Wills RBH, Lim JSK, Greenfield H, Changes in the chemical composition of Cavendish banana (Musa acuminata) during ripening. J Food Biochem 1984;8;69-7.

Leterme P, Buldgen A, Estrada F, Londono AM. Mineral content of tropical fruits and unconventional foods of the Andes and the rain forest of Colombia. Food Chem 2006; 95:644–52.

Berawi KN, Bimandama MA, The Effect of Giving Extract Etanol of Kepok Banana Peel (Musa acuminata) Toward Total Cholesterol Level on Male Mice (Mus Musculus L.) Strain Deutschland-Denken-Yoken (Ddy) Obese. Biomed Pharmacol J 2018;11(2):769-74.

Richard NB, Tânia MS, Neuza MAH, Eduardo ASR, Franco ML, Beatriz RC. Phenolics and Antioxidant Properties of Fruit Pulp and Cell Wall Fractions of Postharvest Banana (Musa acuminata Juss.). Cultivars J Agr Food Chem 2010;58(13):7991-8003

Abdullah FC, Rahimi L, Zakaria ZA, Ibrahim AL. Hepatoprotective, Antiulcerogenic, Cytotoxic and Antioxidant Activities of Musa acuminata Peel and Pulp. Novel Plant Biores 2014;371–82.

Faten AE, Rasha M. Anticancer and anti-oxidant potentials of ethanolic extracts of Phoenix dactylifera Musa acuminata and Cucurbita maxima. Res J Pharma Bio Chem Sci 2015;6(1): 707-20.

Amaal MK, Mervat ST, Amr MM. The Radioprotective and Anticancer Effects of Banana Peels Extract on Male Mice. J Food Nutr Res 2019;7(12):827-35.

Oresanya IO, Sonibare MA, Gueye B, Balogun FO, Adebayo S, Ashafa AOT. Isolation of flavonoids from Musa acuminata Colla (Simili radjah, ABB) and the in vitro inhibitory effects of its leaf and fruit fractions on free radicals, acetylcholinesterase, 15?lipoxygenase, and carbohydrate hydrolyzing enzymes. J Food Biochem 2020;44(3): e13137.

Giri SS, Jun JW, Sukumaran V, Park SC, Dietary Administration of Banana (Musa acuminata) Peel Flour Affects the Growth, Antioxidant Status, Cytokine Responses, and Disease Susceptibility of Rohu, Labeo rohita. J Immuno Res 2016;29:1–11.

Tamri P, Aliasghar H, Amirahmadi A, Zafari J, Mohammadian B, Dehghani M, Evaluation of wound healing activity of hydroalcoholic extract of banana (Musa acuminata) fruit’s peel in rabbit. Pharmacology 2016;3:203-08.

Mothilal B, Prakash C, Ramesh Babu V, Ganapathy, C, Sivamani S. Investigation on the application of Musa acuminata leaf methanol extract on cellulose fabric. J Nat Fib 2020;17:132-39.

Meenashree B, Vasanthi VJ, Mary RNI. Evaluation of total phenolic content and antimicrobial activities exhibited by the leaf extracts of Musa acuminata (banana). Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 2014;3:136-41.

Bankar AM, Dole MN, Formulation and evaluation of herbal antimicrobial gel containing Musa acuminata leaves extract. J Pharm Phytochem 2016;5:1-3.

Navghare VV, Dhawale SC. In-vitro antioxidant, hypoglycemic and oral glucose tolerance test of banana peels. Alex J Med 2017;53(3);237–43.

Luque-Ortega JR, Martínez S, Saugar JM, Izquierdo LR, Abad T, Luis JG, et al, Fungal-elicited metabolites from plants as an enriched source for new Leishmanicidal agents. Antifungal phenyl-phenalenone phytoalexins from the banana plant (Musa acuminata) target mitochondria of Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004;48:1534-1540.

Liyanage R, Rizliya V, Jayathilake C, Jayawardana BC, Vidanarachchi JK. Hypolipidemic activity and hypoglycemic effects of banana blossom (Musa acuminata Colla) incorporated experimental diets in Wistar rats. Sri Lanka Association for the Advancement of Science Proceedings of the 71st Annual Sessions 2015–Part I Section E2 601/E2. 2015.

Benny P, Viswanathan G, Thomas S, Nair A. Investigation of immunostimulatory behaviour of Musa acuminata peel extract in Clarias batrachus. Inst Int Omics Appl Biotech J 2010;1:39-43.

Hont AD, Denoeud F, Aury JM. The banana (Musa acuminata) genome and the evolution of monocotyledonous plants, Nature 2012;488(7410): 213–17.

Singhal M, Ratra P. Investigation of immunomodulatory potential of methanolic and hexane extract of Musa acuminata peel (plantain) extracts. Glob J Pharma 2013;7:69-4.

Okon JE, Esenowo GJ, Afaha IP, Umoh NS, Haematopoietic properties of ethanolic fruit extract of Musa acuminata on albino rats. Bull Environ Pharmacol Life Sci 2013;2:22-26.

Lee KH, Padzil AM, Syahida A, Abdullah N, Zuhainis SW, Maziah M, et al, Evaluation of anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antinociceptive activities of six Malaysian medicinal plants. J Med Plants Res 2011;5:5555-63.

Sumathy V, Lachumy SJ, Zakaria Z, Sasidharan S. In-vitro bioactivity and phytochemical screening of Musa acuminata flower. Pharmacology 2011;2:118-27.

Anal AK, Jaisanti S, Noomhorm A. Enhanced yield of phenolic extracts from banana peels (Musa acuminata Colla) and cinnamon barks (Cinnamomum varum) and their antioxidative potentials in fish oil. J Food Sci Tech 2012;51:2632–639.

Ling SSC, Chang SK, Sia WCM, Yim HS. Antioxidant efficacy of unripe banana (Musa acuminata colla) peel extracts in sunflower oil during accelerated storage. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment 2015;14:343–56.

Lee EH, Yeom HJ, Ha MS, Bae DH. Development of banana peel jelly and its antioxidant and textural properties. Food Sci Biotechnol 2010;19:449-55.

Indexed and Abstracted in

Antiplagiarism Policy: IJCRR strongly condemn and discourage practice of plagiarism. All received manuscripts have to pass through "Plagiarism Detection Software" test before forwarding for peer review. We consider "Plagiarism is a crime"

IJCRR Code of Conduct: To achieve a high standard of publication, we adopt Good Publishing Practices (updated in 2022) which are inspired by guidelines provided by Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association (OASPA) and International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE)

Disclaimer: International Journal of Current Research and Review (IJCRR) provides platform for researchers to publish and discuss their original research and review work. IJCRR can not be held responsible for views, opinions and written statements of researchers published in this journal.

International Journal of Current Research and Review (IJCRR) provides platform for researchers to publish and discuss their original research and review work. IJCRR can not be held responsible for views, opinions and written statements of researchers published in this journal

148, IMSR Building, Ayurvedic Layout,

Near NIT Complex, Sakkardara,

Nagpur-24, Maharashtra State, India

editor@ijcrr.com

editor.ijcrr@gmail.com

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

Copyright © 2026 IJCRR. Specialized online journals by ubijournal