IJCRR - 13(9), May, 2021

Pages: 99-102

Date of Publication: 07-May-2021

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

A Study on Clinical Spectrum, Laboratory Profile, Complications and Outcome of Pediatric Scrub Typhus Patients Admitted to an Intensive Care Unit from a Tertiary Care Hospital from Eastern India

Author: Kumar S, Prusty JBK, Priyadarshini D, Choudhury J, Dash M, Rath D, Praveen SP

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Introduction: Scrub typhus is an emerging mite born infectious febrile illness in children caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi. This study overviews the various clinical, laboratory characteristics, complications outcome of scrub typhus patient.

Objective: Scrub typhus is a common differential diagnosis of fever of unknown origin in children. It is often associated with complications involving many organ systems needing admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). It affects healthy children of all age groups and a delay in diagnosis can prove fatal. The study was conducted to study clinical spectrum, laboratory profile, complications and outcome of scrub typhus patients admitted to pediatric intensive care unit, to estimate the burden of scrub typhus as a cause of admission to PICU.

Methods: It was a prospective, observational study conducted on all pediatric patients admitted to PICU with a diagnosis of scrub typhus over a period from Aug 2018 to July 2019. Clinical, laboratory data along with complications and outcome were studied in all cases.

Results: Out of the total of 122 scrub typhus patients, 30(24.59%) patients were admitted to PICU. Scrub typhus contributed to 8.24% of total PICU admission. Shock (40%) was the most common complication followed by meningoencephalitis(13.33%) and acute respiratory disease syndrome (ARDS) (13.33%).

Conclusion: Scrub typhus is an emerging cause of intensive care admission in recent times. Timely diagnosis and early treatment can prevent complications and reduce the financial burden to a great extent.

Keywords: Scrub typhus, Complications, Shock, Acute respiratory disease syndrome (ARDS), Meningoencephalitis, Pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission

Full Text:

Introduction

Scrub typhus is an emerging mite born infectious febrile illness in children caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi.1 The spectrum of clinical manifestation of scrub typhus is very broad. Though most of the infections are mild to moderate in severity, the mortality rate is quite high in untreated patients ranging from 0 % to 30 % 2 As the clinical features of scrub typhus mimic many of the common viral, protozoal and bacterial infections, the diagnosis is often delayed leading to complications and damage to vital organs and admission to the intensive care unit. The classical presentation of fever, headache, lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, rash and typical eschar are not seen so often in children posing a diagnostic dilemma.3,4 Though it can be diagnosed by relatively inexpensive tests like IgM ELISA and can be treated easily with drugs like doxycycline and azithromycin, delayed presentation leads to complications like meningoencephalitis, myocarditis, shock, respiratory distress, renal failure and multiple organ dysfunction syndromes (MODS) leading to admission to admission to a pediatric intensive care unit.5 Considering the simple and cheap modality of treatment and the good outcome it is often necessary to start empiric therapy for scrub typhus in pediatric cases presenting as an undifferentiated febrile illness with multisystem involvement.6 we aimed to study the various clinical, laboratory characteristics, complications outcome of scrub typhus patient.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a prospective observational study in children below 14 years of age admitted to the Department of Pediatrics of IMS and SUM HOSPITAL, during the period between August 2018 and July 2019, with a clinical diagnosis of scrub typhus. The ethical committee approval was taken from the institutional ethical committee. Those patients who were laboratory confirmed by IgM ELISA as scrub typhus were studied after taking parental consent and patients needing admission to PICU were followed and evaluated in detail.

The clinical diagnosis of cases was based on Rathi – Goodman Aghai scoring for scrub typhus.6 Laboratory confirmation of cases was done by Scrub IgM ELISA. Those serologically confirmed patients who needed admission in PICU were the study participants and were followed up in detail.

The clinical data, complete blood counts along with other laboratory profile, treatment details, complications, the outcome were noted in each case. Multi-organ dysfunction was defined as the involvement of 2 or more system simultaneously.7 The need for inotrope support, mechanical ventilation, transfusion of blood products and other interventions were noted. Thrombocytopenia was defined as a total platelet count less than 1.5 lakh/mm3. Hyponatremia was defined as serum sodium less than 135meq/L, hypoalbuminemia was defined as serum albumin less than 3.5 gm%.

All patients were treated with intravenous doxycycline at a dose of 4 mg/kg/day in two divided doses followed by an oral continuation of doxycycline once the child was able to take orally for a total duration of 7 to 10 days. Various complications like myocarditis, respiratory distress syndrome, meningoencephalitis were treated as per need on case to case basis. The outcome was noted as death, survival, and the meantime for fever defervescence and mean duration of PICU stay were recorded. Qualitative variables were described as number and percentage. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean (SD), median (IQR) wherever applicable.

Results

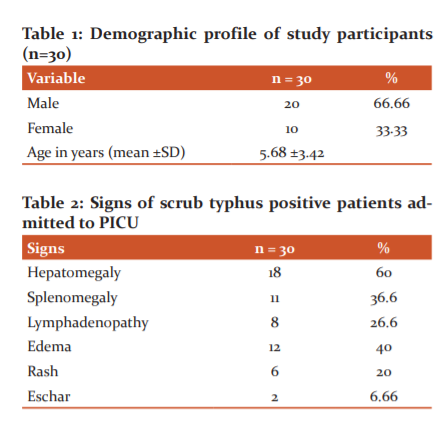

From August 2018 to July 2019 a total of 151 cases were admitted with a clinical diagnosis of scrub typhus. Out of them, 125 cases were serologically positive for scrub typhus. Three cases were excluded from the study due to confection with malaria (1case) and dengue fever in (2 cases ).122 number of lab-confirmed IgM ELISA positive cases were studied. Out of these 122 cases, 30 (24.59%) cases were admitted to PICU for various complications. Scrub typhus contributed to9.96 % of total PICU admission during the study period. The mean age of presentation was 5.68(± 3.42) years. The male to female ratio was 2:1(Table 1).

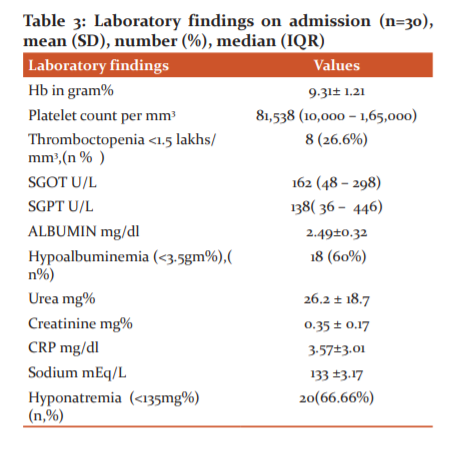

Out of various clinical signs, Hepatomegaly has seen in 18 (60%) cases followed by oedema 12 (40%), splenomegaly in 11(36.6%) cases and lymphadenopathy (26.6 %). Eschar was found only in 2(6.66%) cases (Table 2). Among the laboratory parameters, thrombocytopenia with a total platelet count less than 1.5lakhs/ cm was seen in 8(26.6%) cases, deranged liver function test was seen in 20(66.66 %) cases. Hypoalbuminemia with Serum albumin <3.5 g% was seen in 18(60 %) cases and hyponatremia with serum sodium < 135meq/L was seen in 20(66.66%) cases (Table 3).

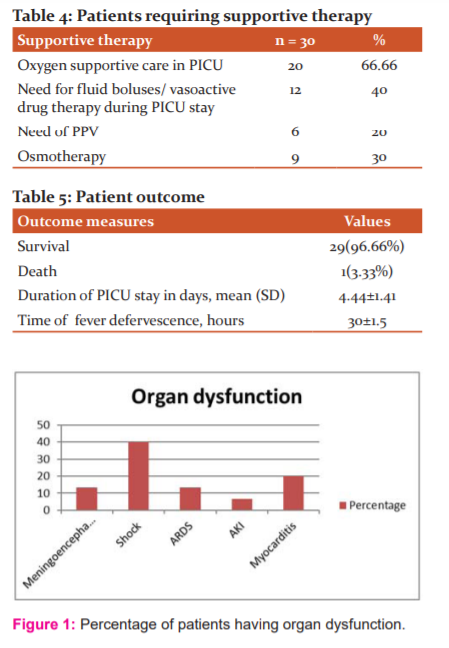

Among the complications and organ dysfunction 12(40%) patients presented with shock, 4(13.3 %) patients had meningoencephalitis, 4(13.3 %) had acute respiratory distress,6 ( 20 % ) patients had myocarditis, and 2(6.66 %) cases had Acute kidney injury (AKI) (Figure 1). Among the supportive therapy 66.66% cases needed oxygen support, 40% of patients needed inotropes,20 % needed mechanical ventilation,6.66% cases needed transfusion with blood products (Table 4).

All the patients were given intravenous Doxycycline at 4 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses, which was changed to oral once the child was stable and able to take orally. The mean duration of fever defervescence was 30±1.5hrs of initiation of Doxycycline. The mean duration of PICU stay was 4.4±1.41 days. There was 1 (3.33%) death in our study population who developed disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with severe bleeding and died within 48 hours of admission, with complete recovery in the rest of the cases (Table 5).

Discussion

During the study period, out of 122 lab-confirmed cases of scrub typhus, 30 cases (24.59 %) needed admission to PICU, which is similar to results in a study by Meena et al. where 20 % of patient needed PICU admission.8 Out of 30 cases, 29 (96.66%) cases had complete recovery without any residual disease symptoms and 1 case died (3.33 %) with a case fatality rate of 3.33%. Another study in 130 scrub typhus patients and mortality was seen in 6.2 %.9 Similar studies by Christal et al. and Palanivel et al. found the overall mortality to be 12.2 % and 11.94 % respectively.10,11 Increasing awareness about the varied clinical presentation of scrub typhus and early empirical treatment may be resulting in the gradual decline in the case fatality rate of scrub typhus with time.

The mean age of presentation was 5.68±3.42 years with male predominance, comprising 66.66 % cases as compared to females. A similar study by Sivaraman et al. where they found the mean age of presentation to be 7.2 ± 4) years and 58 % were above 5 years of age.12 More outdoor games and outdoor activities in above five children resulting in exposure to the pathogen results in more number of cases in this age group.

Hepatomegaly has seen in 18 (60%) cases followed by oedema 12 (40%), splenomegaly in 11(36.6%) cases and lymphadenopathy (26.6 %). Eschar was found only in 2(6.66%) of cases which is less as compared to the study by Pravas et al. where hepatomegaly, oedema, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy was seen in 87%,43%,70% and 40% respectively.13-18 The mean duration of illness before presentation most probably defines various clinical signs at the time of presentation to the hospital.

Thrombocytopenia was seen in 8 (26.6 %) cases, deranged liver function test was seen in 20(66.66 %) cases. Hypoalbuminemia was found in 18(60 %) cases similar to the study by Giri et al. Hyponatremia was found in 20(66.66%) cases which are in concordance with study by Narayansamy et al.18,14

Out of all complications, respiratory difficulty was seen in 20 (60.66%) of cases and out of which 6(20%) cases needed positive pressure ventilation in form of invasive and non-invasive ventilation. 4 (13.3 %) cases developed established features of ARDS which is by studies by Bhat et al. and Narayansamy et al where Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was found in 12.1 % and 11 % of cases respectively. 13,14

The shock was seen in 12 (40%) cases in the present study, all of the required fluid bolus followed by vasoactive drug therapy. A similar result was found in the study by Palanivel et al. and Narayansamy et al. where the shock was found in 44.7 % and 46 % cases respectively.11,14 Meningoencephalitis features with altered sensorium, seizure and Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis was seen in 4 (13.3%) cases which in concordance with studies by Kumar et al. 15 However Narayansamy et al 14 had found meningoencephalitis presentation in 29 % of cases.

Myocarditis was found in 6 (20 %) of cases in the present study which is in congruence with studies by Narayansamy et al. where 24 % of cases had features of myocarditis. However, the study by Narayansamy et al. shown myocarditis in only 3% of cases.15 Acute kidney injury was seen in 2 (6.66 %) cases which are similar to another study by Masand et al where 3.3 % of cases had AKI. But other studies Narayansamy et al and Krisha et al. showed a more significant number of cases with AKI i.e. 12 %, 10 % and 16 % respectively.16,17 The small sample size in our case may be attributable to this and a larger study with more participants is needed for a better correlation of the complications. Thrombocytopenia was seen in 26.6 % of cases, but DIC with severe bleeding was seen in 1(3.33%) case which succumbed to the disease. Disseminated intravascular coagulation DIC was seen on 1.5 % of cases in studies by Bhat et al. and Palanivel et al. 13,11 The mean duration of Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) stay was 4.4 (± 1.41) days in the current study which suggest a good response to therapy in the majority of cases.

Conclusion

Scrub typhus is emerging as a significant cause of acute febrile illness in children. Though mortality is low it amounts to enormous morbidity in the pediatric population leading to admission to PICU. Early diagnosis and empirical therapy can certainly cut down the financial burden and improve outcome.

Conflict of Interest: There is no conflict of interest among the authors.

Author Contribution: Jayashree Choudhury: Concept, data collection, and drafting the manuscript. Satish Kumar Sethi, J Bikrant Kumar Prusty, Debashree Priyadarshini: Data collection. Mrutunjay Dash, Debasmita Rath, P Sai Praveen: Data analysis.

References:

-

Batra HV. Spotted fevers and typhus fever in Tamil Nadu Commentary. Indian J Med Res 2007;126:101?3.

-

Rathi N, Rathi A. Rickettsial infections: Indian perspective. Indian Pediatr 2010;47:157?64.

-

Takhar RP, Bunkar ML, Arya S, Mirdha N, Mohd A. Scrub typhus: A prospective, observational study during an outbreak in Rajasthan, India. Natl Med J India 2017;30:69-72

-

Jayaram Paniker CK. Ananthanarayan and Paniker’s Textbook of Microbiology. 7th ed. University Press Pvt. Ltd.; 2008. p. 412?21.

-

Pavithran S, Mathai E, Moses PD. Scrub typhus. Indian Pediatr 2004;41:1254?7.

-

Rathi NB, Rathi AN, Goodman MH, Aghai ZH. Rickettsial diseases in central India: A proposed clinical scoring system for early detection of spotted fever. Indian Pediatr 2011;48: 867?72.

-

Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A. International Consensus Conference on Pediatric Sepsis. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: Definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in paediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005;6:2?8.

-

Meena JK, Khandelwal S, Gupta P, Sharma BS. Scrub typhus meningitis: An emerging infectious threat. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 2015;14:26?32.

-

Gurunathan PS, Ravichandran T, Stalin S, Prabu V, Anandan H. Clinical profile, morbidity pattern and outcome of children with scrub typhus. Int J Sci Stud 2016;4:247?50.

-

Christal A, Boorugu H, Gopinath KG, Prakash JA, Chandy S, Abraham OC, et al. Scrub typhus: An unrecognized threat in South India-Clinical profile and predictors of mortality. Trop Doct 2010; 40:129?33.

-

Palanivel S, Nedunchelian K, Poovazhagi V, Raghunandan R, Ramachandran P. Clinical profile of scrub typhus in children. Indian J Pediatr 2012; 79:1459?62.

-

Sivaraman S, Viswamohanan I, Krishna GR, Jithendranath A, Bai R. Serological prevalence of scrub typhus among febrile patients from a tertiary care hospital in South Kerala. J Acad Clin Microbiol 2020; 22:41-3.

-

Kumar Bhat N, Dhar M, Mittal G, Shirazi N, Rawat A, Prakash Kalra B, et al. Scrub typhus in children at a tertiary hospital in north India: clinical profile and complications. Iran J Pediatr 2014;24(4):387–392.

-

Narayanasamy DK, Arunagirinathan AK, Kumar RK, Raghavendran VD. Clinical-laboratory profile of scrub typhus - an emerging rickettsiosis in India. Indian J Pediatr 2016;83(12–13):1392–1397.

-

Kumar M, Krishnamurthy S, Delhikumar CG, Narayanan P, Biswal N, Srinivasan S. Scrub typhus in children at a tertiary hospital in southern India: clinical profile and complications. J Infect Public Health 2012;5(1):82–88.

-

Masand R, Yadav R, Purohit A, Tomar BS. Scrub typhus in rural Rajasthan and a review of other Indian studies. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2016;36(2):148–153.

-

Krishna MR, Vasuki B, Nagaraju K. Scrub typhus: audit of an outbreak. Indian J Pediatr 2015;82(6):537–540.

-

Giri PP, Roy J, Saha A. Scrub Typhus - A Major Cause of Pediatric Intensive Care Admission and Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome: A Single-Center Experience from India. Indian J Crit Care Med 2018;22(2):107-110.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License