IJCRR - 8(2), January, 2016

Pages: 74-83

Date of Publication: 22-Jan-2016

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

FOOD AVAILABILITY INFLUENCES THE SEASONALITY OF BIRD COMMUNITY IN TROPICAL FOREST, WESTERN GHATS

Author: T. Nirmala

Category: Healthcare

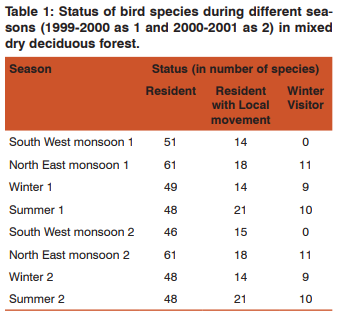

Abstract:Seasonal changes of bird communities in relation with food availability were studied in the mixed dry deciduous forest (MDDF) of Western Ghats. Bird population was estimated using variable width line transect method. Vertical distribution of foliage was sampled in each transect. 51 species of plants comprising 255 individuals were marked for phenological studies. Sweep sampling, visual count, mechanical knock down, light trap, aerial trap and pitfall trap were used for the estimation of arthropods. Bird abundance was high during north-east monsoon and low during south-west monsoon. Total number of species during south-west monsoon was 90 (63%). The main winter visitors were Lesser Whitethroat, Dull Green Leaf-warbler, Blyth's Reedwarbler and Brown Shrike. Species richness was higher during northeast monsoon. Bird Species diversity was found to be greater in MDDF. Winter visitors were high during northeast monsoon. Abundance of birds during different seasons was positively correlated with increasing winter visitor (r = 0.993, p = .001) and this community was largely dominated by insectivore guild. The abundance of arthropod influenced the bird species richness significantly and rainfall showed significant positive correlation with richness of birds. Insect and bird abundance showed significant positive correlation. Increase of Young and mature leaf had no significant correlation with bird abundance. There was a positive significant correlation between Foliage Height Diversity and Bird Species Diversity in all the seasons except summer proving \"Higher foliage profile layers harbour more species\".Total abundance of birds was significantly correlated with total insect abundance.

Keywords: MDDF, Food, Seasonality, Bird community, Tropical forest & foliage height diversity

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

The community composition and densities of bird populations showed spatial and temporal variation due to food resource availability (Hilty 1980, Woinarski and Cullen 1984, Pyke 1985, Levey 1988, Innes 1989, Koen 1992 and Poulin et al. 1994). Besides, climatic factors were also found responsible for such variation in bird species composition (Price 1979, Vijayan 1984) along with time and space (Karr 1971, Greenberg 1981, Loiselle 1988, Blake and Loiselle, 1991). Seasonal variation in the abundance of a species is an adaptive phenomenon (Koen, 1992). The abundance and seasonal fluctuation of insects play a major role in determining the seasonality and biological cycle of the organisms, which are dependent on them for food as majority of the terrestrial birds, are insectivorous. The floral species diversity (Sparks and Parish 1995, Arun 2000), bird (Vijayan et al. 1999) and arthropod abundance (Gunnersson 1996, Arun 2000) influences bird seasonality. Seasonality of birds was scarcely documented in Western Ghats except (Jayson and Mathew 2000). Hence, an attempt was made during 1999-2001 in Anaikatty Hill to monitor the seasonal changes of bird community in the mixed dry deciduous forest (MDDF) with the following objective. • To identify the determinants of the seasonality of bird communities in Anaikatty.

METHODOLOGY Study area Anaikatti Hill (foothills of the Nilgiris in the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, Western Ghats), the mixed dry deciduous forest (MDDF) is situated between 760 39’ and 760 47’E and from 110 5’ to 110 31’N, at an elevation of about 610-1200m above MSL. The MDDF is dominated by plant species such as Acacia leucophloea, Ziziphus mauritiana, Chloroxylon swietenia, Albizia amara, Tamarindus indicus, Albizia lebbeck, Acacia polyacantha, Diospyros ferrea, Cassia fistula and Commiphora caudata. Major shrubs are Chromolaena odorata, Elaeodendron glaucum, Pavetta indica, Lantana camara, Randia dumetorum, Premna tomentosa, Flacourtia indica and Mundulea sericea. Opuntia dillenii and Euphorbia antiquorum are common Succulents.

Methods

Bird population was estimated using variable width line transect method following Bibby et al. (1993). A kilometer length of four permanent transects were laid and marked at every 10m distance. Census was carried-out thrice a month in each transect, early in the morning, half an hour after sunrise in all the seasons and time is limited to one hour. Species diversity and evenness, species richness and relative abundance were determined for each habitat. Foliage Height Diversity (FHD): Vertical distribution of foliage was sampled in each transect of 1 km following the method of MacArthur and Horn (1969) with very little modification as adopted by Daniels (1996) and Gokula (1998). At every 50-m interval, a circular plot of 15-m radius was established. The centre of the circle was considered as the centre point from where an addition of 12 points at every 5m interval on four cardinal directions was established. Ten such similar samples were repeated in all transects. A total of 520 points (10 plots in each transect and 13 points per plot) were made for the vegetation profile study.

From these measurements, the foliage height diversity (FHD) in each stratum was determined using Shannon’s index. Similarly bird species diversity (BSD) was also calculated at each vertical stratum and correlated with foliage height diversity. Plant phenology: Altogether, 51 species of plants comprising 255 individuals were marked for phenological studies. Thirtysix species were selected (plant species preferred by birds for food) and marked with aluminium tag and monitored once in a fortnight for their phenology for two years. The vegetative phase (young leaf and matured leaf=100%) and reproductive phase (buds, flowers, unripe and ripe fruits=100%) of the marked plants were estimated separately in percentages. The data were averaged for each species and given the phenological status during the study period. This data was used to compare frugivore and nectarivore abundance. Arthropod sampling methods: Six major sampling methods were used in the field for the regular sampling of insects, namely sweep sampling, visual count, mechanical knock down, light trap, aerial trap and pitfall trap following Southwood (1971) with slight modifications.

The arthropod collected by different sampling devices per fortnight were identified upto order following Imm’s classification (Richards and Davies 1977). Sweep sampling: The sweeps were done during the morning hours after 08.30 hour along a kilometre length of four transects (laid for bird census) in the mixed dry deciduous forest using sweep net. In total, two hundred and fifty sweeps were taken from each transect at every 100m distance The approximate area of coverage per sweep sampling was 1x10 m2 . Knock down: Mechanical knockdown was made using a bamboo pole and the insects were collected on a tray (1m x 1m). For uniformity, 10 beats were made as a standard for each sample to dislodge the insects. Ten such samples were collected from the fixed places (shrub) in each transect. Light trap: A fabricated light trap based on the design of Mathew (1990) was employed for the purpose of sampling the nocturnal insect abundance. The trap was operated only for an hour during the early night hours (19th hour) in each transect. Aerial trap: Plastic containers filled partly with water and preservative were hung in the canopy for two days (48 hours). 10 such traps per transect at every 100 m distance (60 traps/season) were used to collect aerial arthropods (Erwin T.L and Scott J.C,1980).

Pit-fall trap: Plastic containers filled partly with water and preserving solution were placed on the surface of the ground to get surface dwelling arthropods. 10 such traps were installed at every 100 m distance per transect (60 traps/season) (Erwin T.L and Scott J.C,1980). Visual count /Transect count: Various authors (Pollard 1977, Pollard and Yates 1993, Ishii 1993, Natuhara et al. 1996, Arun 2000) have tested the reliability of this method for estimating butterfly abundance. All the butterflies encountered within 10 x 5-m area were counted and recorded. The count was made in the morning hours (between 08.30 and 11.30 hour) at every 100 m distance along each transect. Abiotic factors, namely minimum temperature, maximum temperature, rainfall, number of rainy days, mean relative humidity and windspeed were obtained from the Meteorology Department, Chennai. Biotic factors affecting insect abundance such as phenology of plants and abundance of birds were monitored twice a month.

Data Analysis Four seasons noticed in Anaikatty were southwest monsoon (June-August), northeast monsoon (September-November),winter (December-February) and summer (March-May). Major statistical tests were employed in analysing the data using the statistical package SPSS (Norusis 1994) and SPDIVERS.BAS.

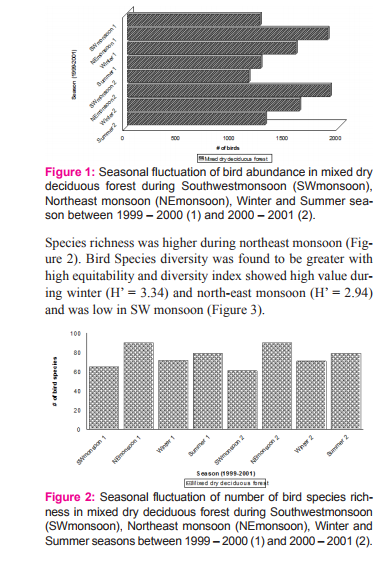

RESULT Seasonality of birds Bird abundance was high during north-east monsoon in MDDF and low during south-west monsoon (Figure 1). Total number of species during south-west monsoon shared by MDDF was 63%. The main winter visitors were Lesser Whitethroat, Dull Green Leaf-warbler, Blyth’s Reed-warbler and Brown Shrike. This was followed by the flocks of altitudinal migrants such as Black Bulbul, Grey-headed Myna, Rosy Pastor, and Blossom-headed Parakeet, and a few locally moving Grey Drongo and Verditor Flycatcher and the resident birds such as Red-whiskered Bulbul, Purple Sunbird, Loten’s Sunbird and Paradise Flycatcher which breed here during north-east monsoon.

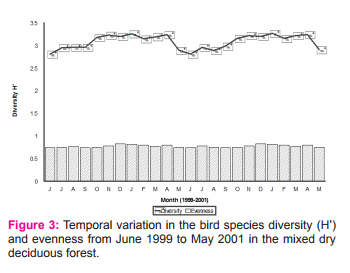

Seasonality of birds based on migratory status The number of species increased consistently to reach the peak (90) during northeast monsoon and found lowest in summer (Table 1). The resident (with local movement) species were the highest during summer while winter visitors were high during northeast. No winter visitor was recorded during southwest monsoon 1 and 2. Total abundance of birds during different seasons was positively correlated with the increasing residents (r = 0.836, p < 0 .01, N = 8). The Common Iora was the most abundant species during southwest 1, Whitebrowed Bulbul was the first dominant species during northeast 1 and 2, summer 1 and 2 and southwest 2 and the Blyth’s Reed Warbler was the dominant species during winter 1 and 2. Abundance of birds during different seasons was positively correlated with increasing winter visitor (r = 0.993, p = .001) and resident with local movements (r = 0.862, p = 0.006).

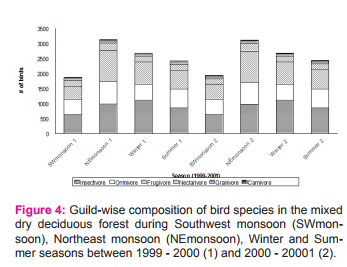

Seasonality of bird abundance on feeding guild composition The avifauna was largely dominated by insectivore guild through out the study period followed by omnivore and frugivore. A definite seasonal pattern existed in all the six guilds (Figure 4). Insectivores occurred all through the seasons with the maximum during winter and minimum during northeast monsoon. Omnivores and carnivores were highly abundant during southwest monsoon and summer and lowest during winter. Frugivores were highly abundant during northeast monsoon and low during southwest monsoon.

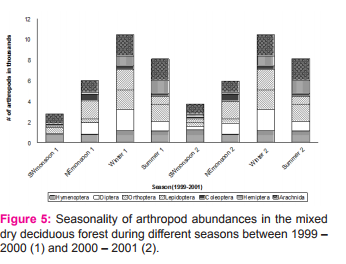

On the contrary, granivores were abundant during southwest monsoon and lowest during northeast monsoon. Nectarivores were found low during winter and high during southwest monsoon. Variation in the total abundance of birds was correlated with the abundance of different guilds in various seasons. Nectarivores (r = 0.795, p = 0.018), insectivore (r = 0.726, p = 0.041) and frugivore (r = 0.952, p = 0.0001) showed significant positive correlation with the total abundance of birds while the other guilds such as granivore, carnivore and omnivore had no such significant correlation. Lepidoptera, Orthoptera and Diptera were significantly higher in the mixed dry deciduous forest during winter, whereas Hymenoptera was the highest during north-east monsoon and Hemiptera was high during summer (Figure 5). Legend: Figure 5. Seasonal fluctuation of arthropod abundances in the mixed dry deciduous forest during different seasons such as Southwestmonsoon (SWmonsoon), Northeast monsoon (NEmonsoon), Winter and Summer between 1999 – 2000 (1) and 2000-2001 (2).

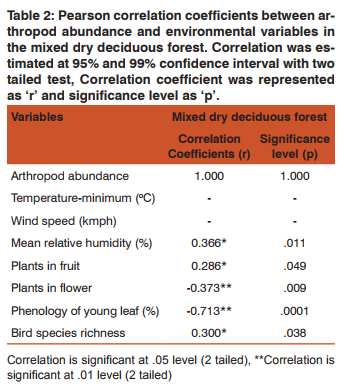

Role of ecological factors on Arthropod Among the six abiotic factors namely minimum temperature, maximum temperature, rainfall, rainy days, mean relative humidity and windspeed, Only mean relative humidity showed significant positive correlation. The abundance of arthropod was influenced by the biotic factors such as plant species in fruit that showed significance positively with the abundance of insects (Table 2). Plant species in flower and phenology of young leaf showed significant negative correlation with the abundance of arthropod which depicts that when young leaves are more, arthropod are low and the vice versa. The effect comes after flushing of leaves and increase of arthropod occurred with a lag period after rain during north-east monsoon which might be the reason for their peak during winter. The abundance of arthropod influenced the bird species richness significantly (Table 2).

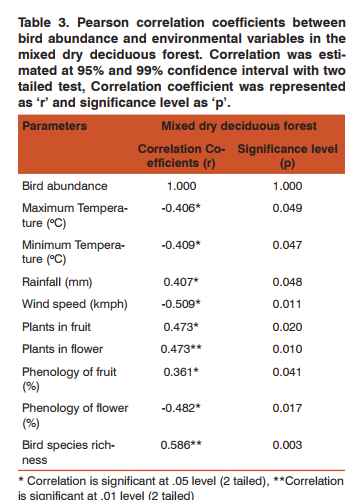

Bird and factors Role of abiotic factors on birds Among the six abiotic factors, maximum temperature, minimum temperature and windspeed showed significant negative correlation with both species abundance and richness (Table 3). Rainfall showed positive correlation with abundance of birds (r= 0.407, p= 0.048). Also rainfall showed significant positive correlation with richness of birds (r = 0.605, p = 0.002).

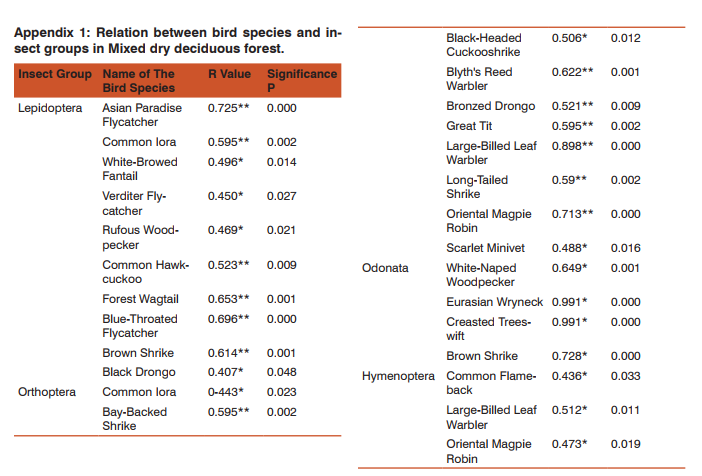

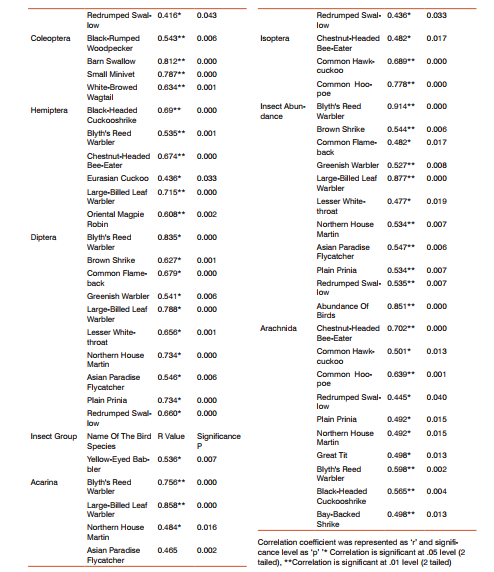

Bird and insect Bird and insect abundance fluctuated highly in Anaikatty hills (Figure 6), 44% of the Anaikatty birds depend on the insects. Bivariate test of Pearson correlation coefficient was used to test the relation between bird and insect abundance. They showed significant positive correlation (r = 0.438, P = 0.032) suggesting that insect abundance positively influenced the abundance of birds. Insectivore bird species with insects showed positive correlation with total insect abundance (r= 0.851, p = 0.0001). Each insectivore bird species was correlated with each insect order and the results are given in Appendix 1.

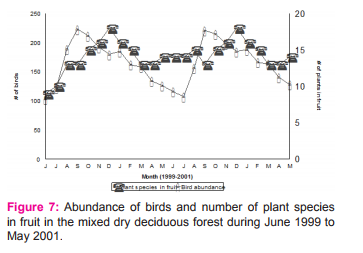

Bird and vegetation Increase of fruiting plants also increased the abundance of birds (Table 3) as total abundance of birds correlated significantly with frugivores (r = 0.952, p = <0.0001). Abundance of birds showed positively significant correlation with number of plant species in fruit (Figure 7, Table 3). Young and mature leaf had no significant correlation with bird abundance. In mixed dry deciduous forest, fruiting reached a peak during the north-east monsoon. The abundance of frugivores synchronised with the abundance of fruits (r = 0.449, p = <0.028).

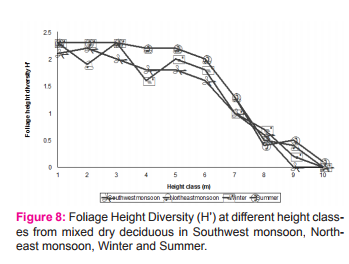

Foliage Height Diversity (FHD) To relate bird community structure with habitat, vertical distribution of the foliage was sampled following MacArthur and Horn (1969). Foliage thickness was recorded at different strata seasonally and FHD was calculated for each stratum. In mixed dry deciduous forest, foliage was available upto 11-12m. Foliage height diversity was estimated upto 12m (Figure 8). Foliage Height Diversity was greater up to 6 m height class and decreased as the height increased because of the fewer number of tall trees. The higher strata were dominated largely by tree species such as Acacia polyacantha, Albizia lebbeck, Tamarindus indicus and Ficus species.

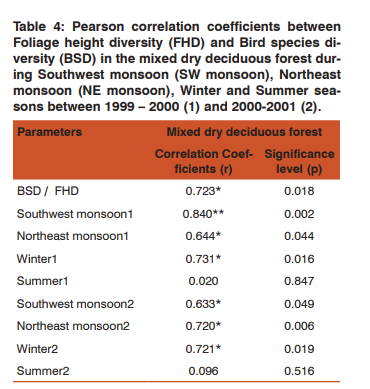

Seasonality of Foliage Height Diversity (FHD) and Bird Species Diversity (BSD) Indices of BSD and FHD was correlated to test its dependency on FHD and test the hypothesis “Higher foliage profile layers harbour more species”. There was a positive significant correlation between FHD and BSD in all the seasons except summer (Table 4). All the other seasons showed significant result towards the influence of BSD by FHD. Moreover, the BSD and FHD significantly correlated altogether with MDDF (r=0.723*, p= 0.018). Foraging data was stratified according to the height and diversity was estimated to correlate with FHD, and it resulted with significant correlation (Table 4). This hypothesis became true with habitat MDDF, where the Pearson correlation coefficients gave significant result positively.

Insectivore birds and insects Large-Billed Leaf Warbler, Greenish Warbler, Plain Prinia, Brown Shrike, Common Flame-back, Blyth’s Reed Warbler, Brown Shrike, Lesser Whitethroat, Red-rumped Swallow and Oriental Magpie Robin were affected directly by the insect abundance in MDDF (Appendix 1). Total abundance of birds was significantly correlated with total insect abundance in MDDF. Asian Paradise Flycatcher, Blyth’s Reed Warbler and Brown Shrike were consistently increased with insect abundance. Shrikes, Warblers, Flycatchers, Drongos, Common Iora, Yellow-eyed Babbler, Oriental Magpie Robin, White-browed Wagtail, Chestnut-Headed Bee-Eater, Plain Prinia, Black-rumped Woodpecker, Rufous Woodpecker, Asian Paradise Flycatcher, Bee-eaters, Swifts and Swallows significantly increased with insect abundance (appendix 1).

DISCUSSION Seasonal fluctuation in birds is a phenomenon found in various habitats. In drier habitats bird species richness and abundance was initiated during monsoon as found by Johnsingh and Joshua (1994) as against the wet forests found by Jayson and Mathew (2000). During northeast monsoon the species richness and abundance was high in mixed dry deciduous forest whereas low in Mukkali showing that there is a possibility of the birds to migrate locally from there to mixed dry deciduous forest for example Black Bulbul, Grey-headed Bulbul, Pigeon etc. as suggested by Raman (1999) in Kalakkad - Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve and Jayson and Mathew (2000) in Silent Valley. So mixed dry deciduous forest becomes a wintering place for the high altitudinal birds since they found this area suitable during unfavourable climatic condition elsewhere. Gaston’s (1978c) study on the New Delhi ridge also showed similar results where diversity was high during winter and low in summer.

The present result showed that population of avifauna considerably changes between seasons. Species abundance was more during north-east monsoon than during the winter season. Species richness was more during north-east monsoon as reported in the moist deciduous forest (Gokula 1998, Vijayan et al .1999). Presence of locally moving birds and winter visitors are one of the major factors responsible for the higher diversity in the north-east monsoon. Food availability was also high during this season. It could be discussed that the abundance of insects, availability of fruits and rainfall attracted more birds. The seasonal variation in the occurrence of birds could be due to fluctuation in the abundance of food as insect numbers relates with rainfall as studied by Karr (1976b), Vijayan (1984) and Vijayan et al. (2000). But not with leaf flush as in the studies of Price (1979) and Johnsingh et al. (1987). As it has been established in the insect herbivores of the tropical savannas (Price et al. 1995) and leaf miners of Mexico (Nestel et al. 1994), in this study also, the overall insect abundance of the area did not show a direct significant relation with the plant phenology.

But when the young leaves are few and tender, the insect abundance was high. 44% of bird are dependent on insect alone. Avifauna of mixed dry deciduous forest becomes stable which shows frugivore and insectivore are the major guild forming community, which depends on fruits and insects. However, insectivores of mixed dry deciduous forest were depending on insects (50%), as found by Vijayan (1984). In general, the insectivores and frugivores were the dominant groups and showed distinct seasonal fluctuations in their abundance. Insectivores were invariably high during winter was due to the greater abundance of insect during this season.

Abundance of more insectivores in winter season was also because of the migrants, most of whom are insectivores. Among the arthropod groups, Arachnida, Hymenoptera, Diptera and Lepidoptera were the most abundant groups and were consistently high during winter. Seasonality pattern varied among insect orders. More number of rainy days were found to favour the insect abundance, which differed significantly among the seasons. Mixed dry deciduous forest recorded the highest arthropod abundance and this was determined by the habitat condition. Although the arrival of migrants started from September they stayed till early May; the abundance of warblers and flycatchers were more as they largely obtained their insectfood from shrubs. Moreover, the availability of migrants was higher as reported by Katti and Price (1996) in Kalakad and Vijayan et al. (2000) in Siruvani.

The greater availability of foraging substrate and less inter-specific competition on foraging substrate might influence the population of warblers and flycatchers, which contributed to an increase in the overall insectivore population during winter as found in Mudumalai by Gokula (1998). Nectarivore, carnivore and frugivore species were fewer in the habitat as witnessed by Sundaramoorthy (1991), Gokula and Vijayan (1996), Gokula (1998) and Vijayan et al. (2000). The insects emerged in relation to rainfall and their abundance increased as the rainy season progressed as in the study of Murali and Sukumar (1993) in deciduous forest of Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary. Bird species such as Asian Paradise Flycatcher, Blyth’s Reed Warbler and Brown Shrike were consistently increased with insect abundance. Shrikes, Warblers, Flycatchers, Drongos as in (Vijayan 1984), Common Iora, Yellow-eyed Babbler (Nirmala and Vijayan 2000), Oriental Magpie Robin, White-browed Wagtail, Chestnutheaded Bee-Eater, Plain Prinia, Black-rumped Woodpecker, Rufous Woodpecker, Asian Paradise Flycatcher (Gokula 1996, 1998). Fruiting reached a peak during the north-east monsoon in Anaikatty hills as in the report of Balasubramanian et al. (1998).

The abundance of frugivores synchronised with the availability of fruits in mixed dry deciduous forest because of more frugivores in MDDF. It is apparent from the above discussions that the abundance of food and its availability regulate the number of birds as in Karr et al. (1992) and Pramod (1995). The increase in abundance of birds was because of the increase of endemic birds (Malabar Parakeet and Rufous Babbler), winter visitors and local migrants. High influx of species was because of immigration. Low species richness during southwest monsoon was due to emigration of migrants. Variation in the seasons was found in the region of Silent valley and Mukkali (Pramod 1995) where the diversity was profoundly high during summer.

This variation was due to the habitat change in MDDF having more plants and foliage cover in the canopy. In mixed dry deciduous forest, fruiting reached a peak during the north-east monsoon as in the report of Balasubramanian et al. (1998). which is also a cause added to the abundance of birds. MacArthur and MacArthur (1961) related the foliage complexity with the bird species diversity and stated that higher foliage profile layers harboured more species. This is true with habitat of mixed dry deciduous forest and similar studies elsewhere (Johnsingh et al. 1987, Vijayan et al. 1999).

CONCLUSION The communities of avifauna considerably change between seasons. The seasonal variation in the occurrence of birds was due to fluctuation in the abundance of food as insect abundance and fruiting species. Southwest monsoon was only for a few days but more number of rainy days was in northeast monsoon which resulted in blooming of insects and increasing insectivores. Frugivores increased with more number of fruiting species.

More number of rainy days were found to favour the insect abundance, which differed significantly among the seasons. Mixed dry deciduous forest recorded the highest arthropod abundance and this was determined by the habitat condition. There exists a definite trend and peak of frugivore during north-east monsoon, insectivore during winter, nectarivore and granivore during south-west monsoon. Insectivores are dominant group and formed 50% and showed distinct seasonal fluctuations in their abundance. Insectivores were invariably high during winter was due to more insect abundance during this season.

The greater availability of foraging substrate and less inter-specific competition on foraging substrate influenced the population of warblers and flycatchers, which contributed to an increase in the overall insectivore population during winter. The abundance of frugivores synchronised with the availability of fruits. No distinct pattern was found in nectarivores. When young leaves are more, insects are low and 44% of birds are dependent mainly on insects.

Avifauna showed frugivore and insectivore as the major guild, which depended on fruits and insects. Insectivores such as Large-Billed Leaf Warbler, Greenish Warbler, Plain Prinia, Brown Shrike, Oriental Magpie Robin, Asian Paradise Flycatcher, Blyth’s Reed Warbler and Brown Shrike consistently increased with insect abundance. Shrikes, Warblers, Flycatchers, Drongos, Common Iora, Yellow-eyed Babbler, Oriental Magpie Robin, Whitebrowed Wagtail, Chestnut-headed Bee-eater, Plain Prinia, Black-rumped Woodpecker, Rufous Woodpecker, Asian Paradise Flycatcher, Bee-eaters, Swifts and Swallows also increased significantly with insect abundance. These species directly depended on insects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am greatful to my supervisor Dr. Lalitha Vijayan and Salim Ali centre for Ornithology, Coimbatore. I express the deep sense of gratitude to the University Grants Commission for providing the grant and Jayaraj Annapackiam College for Women ( Autonomous), Periyakualm.

References:

1. Arun, P. R. (2000): Seasonal variations in the abundance of insect groups in a natural moist deciduous forest of Western Ghats. Ph. D. Thesis, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore.

2. Balasubramanian, P., S. N. Prasad and K. Kandavel (1998): Role of birds in seed dispersal and natural regeneration of forest plants in Tamil Nadu. Technical report of Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History and Tamil Nadu Forest Department (Research wing). pp. 44.

3. Bibby, C. J., N. D. Burgess and D. A. Hill (1993): Bird census techniques. British Trust for Ornithology and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Academic Press, London. pp. 66-84.

4. Blake, J. G. and B. A. Loiselle (1991): Variation in resource abundance affects capture rates of birds in three lowland habitats in Costa Rica. Auk. 108: 114-130.

5. Daniels, R. J. R. (1996): Landscape ecology and conservation of birds in the Western Ghats, South India. Ibis. 138: 64-69.

6. Erwin T.L and Scott J.C (1980) Seasonal and Size patterns. trophic structure and richness of Coleoptera in the tropical arboreal ecosystem: the fauna of the tree Leuhea seemanniTriana and Planch in the canal Zone of Panama. Coleopterists Bulletin, 34; 305-322.

7. Gaston, A. J. (1978c): Distribution of birds in relation to vegetation in the New Delhi ridge. J. Bombay nat. Hist. Soc. 75 (2) : 257- 265.

8. Gokula, V. (1998): Bird communities of the thorn and dry deciduous forests in Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, South India. Ph. D. Thesis, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore.

9. Gokula, V. and L. Vijayan (1996): Birds of Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary. Forktail. 12: 107-117.

10. Greenberg, R. (1981): The abundance and seasonality of forest canopy birds on Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Biotropica. 13: 241-251.

11. Gunnersson, B. (1996): Bird predation and vegetation structure affecting spruce living Arthropods in a temperate forest. Journal of Animal Ecology. 65(3): 389-397.

12. Hilty, S. L. (1980): Flowering and fruiting periodicity in a premontane rain forest in Pacific Colombia. Biotropica. 12: 292-306.

13. Innes, G. J. (1989): Feeding ecology of fruit pigeons in subtropical rainforests of Southeastern Queensland. Aust. Wildl. Res. 16: 365-394.

14. Ishii, M. (1993): Transect count of butterflies. In Decline and conservation of butterflies in Japan 11: 91-101.

15. Jayson, E. A., and D. N. Mathew (2000): Seasonal changes of tropical forest birds in the southern western ghats J. Bombay nat. Hist. Soc. 97 (1): 52- 61.

16. Johnsingh, A. J. T., and J. Joshua (1994): Avifauna in three vegetation types on Mundanthurai Plateau, South India. J. Tropical Ecology. 10: 323-335.

17. Johnsingh, A. J. T., N. H. Martin., J. Balasingh., and V. Chelladurai (1987): Vegetation and avifauna in a thorn scrub habitat in South India. Tropical Ecology. 28: 22-34.

18. Karr, J. R. (1971): Structure of avian communities in selected Panama and Illinois habitats. Ecol. Monogr. 41: 207-233.

19. Karr, J. R. (1976b): Seasonality, resource availability and community diversity in tropical bird communities. American Naturalist. 110: 973-994.

20. Karr, J. R., M. Dionne and I. J. Schlosser (1992): Bottom-up versus top-down regulation of Vertebrate populations: Lessons from birds and fish. In. Effects of resource distribution on animal plant interactions. Academic press Inc. pp. 243-286.

21. Katti, M. and J. Price (1996): Effects of climate on palaearctic warblers over-wintering in India. J. Bombay nat. Hist. Soc. 93(1): 411-427.

22. Koen, J. H. (1992): Medium-term fluctuations of birds and their potential food resources in the Knysna forest. Ostrich. 63: 21-30.

23. Levey, D. J. (1988): Spatial and temporal variation in Costa Rican fruit and fruit-eating bird abundance. Ecol. Monogr. 58: 251-269.

24. Loiselle, B. A. (1988): Bird abundance and seasonality in Costa Rican lowland forest canopy. Condor. 90: 716-722.

25. MacArthur, R. H. and H. S. Horn (1969): Foliage profile by vertical measurements. Ecology. 50: 802-804.

26. MacArthur, R. H. and J. W. MacArthur (1961): On bird species diversity. Ecology. 42: 594-598.

27. Mathew, G. (1990): Studies on the Lepidoptera fauna. In. Ecological studies and long-term monitoring of the biological processes in the Silent Valley National Park. Report submitted to Ministry of Environment, Govt. of India, Kerala forest Research Institute. pp. 239.

28. Murali, K. S. and R. Sukumar (1993): Leaf flushing phenology and herbivori in a tropical dry deciduous forest, Southern India. Oecologia. 94: 114-119.

29. Natuhara, Y., C. Imai, M. Ishii, Y. Sakuratani and S. Tanaka (1996): Reliability of transect count method for monitoring butterfly communities;1. Repeated counts in an urban park. Japaneese Journal of Environmental Entomology and Zoology. 8(1): 13-22.

30. Nestel, D., F. Dicksschen and A. Altieri (1994): Seasonal and spatial population loads of a tropical insect: The case of the coffee leaf miner in Mexico. Ecological Entomology. 19(2): 159- 167.

31. Nirmala, T. and L. Vijayan (2000): Ecology of the Yellow-eyed Babbler. Proc. of Second Pan Asian Ornithological Congress. 27: 2.

32. Norusis, M. J. (1994): SPSS Inc. SPSS release 6.0 for Unisys 6000, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

33. Pollard, E. (1977): A method for assessing changes in the abundance of butterflies. Biological conservation. 12: 115-131.

34. Pollard, E. and T. J. Yates (1993): Monitoring butterflies for Ecology and Conservation. Chaman and Hall, London. pp. 274.

35. Poulin, B., G. Lefebvre and R. McNeil (1994): Characteristics of feeding guilds and variation in diets of birds species of three adjacent tropical sites. Biotropica. 26: 187-197.

36. Pramod, P. (1995): Ecological studies of Bird communities of Silent Valley and neighbouring forests. Ph. D. Thesis submitted to the university of Calicut, Kerala.

37. Price, P. W. , I. R. Diniz, H. C. Moraise and E. S. A. Marques (1995): The abundance of insect herbivore species in the tropics: the high richness of rare species. Biotropica. 27(4): 468-478.

38. Price, T. D (1979): The seasonality and occurrence of birds in the Eastern Ghats of Andhra Pradesh. J. Bombay nat. Hist. Soc. 76 (3): 379 - 422.

39. Pyke, G. H. (1985): Seasonal patterns of abundance of insectivorous birds and flying insects. Emu. 85: 34-39.

40. Raman, T. R. S. (1999): Flocking and altitudinal movements of the Black Bulbul Hypsipetes madagascariensis in the southern western ghats, India. J. Bombay nat. Hist. Soc. 96(2): 320-321.

41. Richards, O. W. and R. G. Davies (1977): Imm’s General Text Book of Entomology, 10th edition; vol 2,Classification and Biology. Chapman and Hall, London pp. 933.

42. Southwood, T. R. E. (1971): Ecological methods with particular reference to insect populations. English Language Book Society. pp.524.

43. Sparks, T. H. and T. Parish (1995): Factors affecting the abundance of butterflies in the field boundaries in Swaresey fens. Cambridge, U. K. Biological conservation. 73(3): 221.

44. Sundaramoorthy, T. (1991): Ecology of terrestrial birds inKeoladeo National Park, Bharatpur. Ph. D. Thesis, Bombay University, Bombay.

45. Vijayan, L. (1984): Comparative biology of Drongos (Family: Dicruridae, Class: Aves) with special reference to ecological Isolation. Ph. D. Thesis, Bombay University, Bombay.

46. Vijayan, L., S. N. Prasad, P. Balasubramanian V. Gokula, N.K. Ramachandran, D. Stephen and M. V. Mahajan (1999): Impact of human interference on the plant and bird communities in the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. Final report, SACON.

47. Vijayan, L., V. Gokula and S. N. Prasad (2000): A study of the Population and habitat of the Rufous-breasted Laughing Thrush Garrulax cachinnans. Project report, SACON. pp. 26.

48. Woinarski J. C. Z. and J. M. Cullen (1984): Distribution of invertebrates on foliage in forests of south-eastern, Australia. Aust. J. Ecol. 9: 207-232.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License