IJCRR - 12(18), September, 2020

Pages: 136-141

Date of Publication: 22-Sep-2020

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

Vertigo in Pediatric Age: Often Challenge to Clinicians

Author: Santosh Kumar Swain, Satyabrata Achary, Saurjya Ranjan Das

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Vertigo or dizziness is perceived to be a common handicapping clinical entity in all the age group of the human being. Vertigo is an uncommon symptom in pediatric age group and rarity of this clinical entity may be due to unrecognized in children. It is often associated with a range of otological, neurological and psychiatric diseases. In younger children, benign paroxysmal vertigo is often seen whereas vestibular migraine is common in adolescent girls. The aetiology of the pediatric vertigo is usually multifactorial, so each pediatric patient with vertigo should be approached in an open mind. Thorough history taking is important for getting a diagnosis of pediatric vertigo. Establishing the diagnosis of vertigo or dizziness is often challenging, especially in the pediatric age group. This article is a narrative review discussion on prevalence, etiopathology, clinical manifestations and management of pediatric vertigo. This review article will make a baseline from where further prospective trials can be designed and help as a spur for further research in this clinical entity as there are not many studies of pediatric vertigo.

Keywords: Pediatric age, Vertigo, Vestibular migraine, Benign paroxysmal vertigo, Meniere’s disease, Vestibular neuritis

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Vertigo is common complaint posed to a clinician in routine clinical practice. Vertigo is considered as the most common causes for referral to neuro physician and Otorhinolaryngologists in office-based settings and emergency clinics1. Vertigo is described as as a subjective sensation of movement, typically spinning or turning, in absence of actual movement of the body2. Vertigo is not an uncommon clinical symptom in pediatric age group, though it may often unrecognized. Disorders that cause vertigo in pediatric age vary concerning one another in many ways. Vertigo or dizziness may be a nonspecific squeal of the several impairments including problems in proprioception, vision, vestibular function, musculoskeletal and autonomic systems2. Proper history taking is often difficult to obtain because of the pediatric age and unable to tell their clinical symptoms precisely. There is an added challenge faced by the clinician in evaluating and managing pediatric vertigo owing to a lack of the proper history, practical difficulties during clinical examination and a lack of standard objective evaluation methods. Here, this review article discusses the aetiology, prevalence, clinical presentations, diagnosis and treatment of pediatric vertigo. This review article aims to give awareness among the readers with the difficult clinical entity such as vertigo, particularly in the pediatric age group.

METHODOLOGY

We conducted an electronic search of the SCOPUS, Medline and PubMed databases for searching the published articles. The search terms in the database included vertigo, pediatric age, dizziness and impairment of balance in children. The abstracts of the published articles are identified by this search method and other articles were identified manually from these citations. This review article reviews vertigo in the pediatric age group including the etiopathology, prevalence, presentations, diagnosis and current treatment. This review article presents a baseline from where further prospective trials can be designed and help as a spur for further research in this clinical entity where not many studies are done.

PREVALENCE

Dizziness and balance disorders are thought to be uncommon in the pediatric age group. This may be due to poor understanding of the epidemiology of vertigo or balance problems in children 3. The literature for pediatric vertigo is scant. Prevalence of vertigo in the pediatric age group ranges from 8% to 15% 4. In otolaryngology clinic, the prevalence of the pediatric vertigo patients constitutes around 0.7% 5. A study in Scotland with 2165 pediatric patients with an age range from 5 to 15 years found the one-year prevalence of one episode of rotary vertigo to be 18% along with the prevalence of reducing to 5% for minimum three episodes [6]. One study sampled 1050 children with an age range from 1 to 15 years in Finland and found the lifetime prevalence of vertigo to be 8% and that for poor body balance to be 2% 4. Episodic vertigo and dizziness are usually uncommon in pediatric age group than in the adult population. Valid estimation of the prevalence of vertigo among pediatric age group must be determined when someone considers that such clinical symptoms could have some adverse psychosocial associations like anxiety and avoidance behaviour, which leads to child’s educational impairment and poor quality of life 7. It is also vital that physicians should keep it in mind and aware of those characteristic features of vertigo or dizziness in pediatric patients, so that appropriate intervention can be provided.

ETIOLOGY AND TYPES OF VERTIGO IN PEDIATRIC AGE

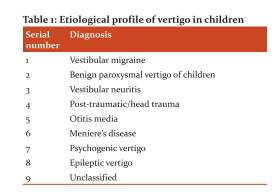

The aetiology of vertigo in children is multi-factorial, so the management depends on accurate diagnosis. Vertigo in the children is broadly classified into Acute nonrecurring spontaneous vertigo, recurrent vertigo and non-vertiginous dizziness, disequilibrium and ataxia. Vestibular migraine and benign paroxysmal vertigo are commonly found cause for vertigo in pediatric age. The common differential diagnosis of vertigo in the pediatric age group is discussed below.Table.1 showing the differential diagnosis in higher than two thousand pediatric patients with vertigo and dizziness obtained by a group of clinicians 8.

Vestibular migraine

Majority of the pediatric vertigo is due to vestibular migraine. The patient typically presents with headache, cyclical vomiting, abdominal pain, vertigo, recurrent episodes of pyrexia or head banging, attacks of pallor and somnolence. The diagnosis of the vestibular migraine in children needs awareness where a meticulous history for headache and careful family history towards migraine is an important part of the diagnosis. However, vestibular migraine remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Neuhauser and Lempert (2009) used the term vestibular migraine as it stresses the vestibular manifestations of migraine 9. It is often seen in adolescent girls and is usually associated with menstrual periods. The vertigo is associated with a headache which lasts for hours with nausea and vomiting as well as photophobia and phonophobia. Sensory stimuli like intense smell, bright lights and loud noise may precipitate the attack. A history of motion sickness is often associated with a family history of migraine. The otologic, neuro-otologic, general physical and vestibular examinations are often normal in between the episodes of the vestibular migraine 10.

Benign paroxysmal vertigo (BPV)

The characteristic features of the BPV in pediatric age are recurrent brief attacks of vertigo without any warning and resolving spontaneously in otherwise normal child 11. BPV is a common cause of vertigo in pediatric patients, showing with a prevalence of 2.6% 12. It is often reported classically at less than four years of age and uncommon after 8 years of the age 13. The etiopathology of this clinical entity is still not known. It appears to occur due to vascular changes which produce transient hypoxia at the vestibular nuclei and the vestibular pathways. This type of pathophysiology of BPV is similar to the pathophysiology of the migraine; so the majority of pediatric patients with BPV will develop migraine in later part of the life 13. There are no presentations of altered consciousness, neurological abnormalities and audiovestibular changes during the attack. The vestibular evoked myogenic potential l (VEMP) and caloric test results support the diagnosis. In the majority of BPV patients, thermal caloric tests show asymmetry 14. The prognosis of BPV is usually favourable and tends to disappear spontaneously before adolescence age.

Post-traumatic vertigo

Children having post-traumatic vertigo without any deafness in the pediatric age could be due to labyrinthine concussion whiplash syndrome, vertiginous seizures, basilar artery migraine or non-specific dizziness 15. In the case of temporal bone fracture, inner ear disruption may happen which results in vestibular dysfunction and leakage of the cerebrospinal fluid. Temporal bone trauma may lead to perilymphatic fistula which can occur even without evidence of the fracture line in temporal bone and often associated with the fluctuating type of deafness16. Surgical closure of the labyrinthine fistula can reduce the vertiginous symptoms completely but the deafness may not be recovered 17. After trauma to the labyrinth, pediatric patients may exhibit abnormal results of the vestibular tests in approximately half of the cases, even children are asymptomatic 18. After trivial trauma in case of children with congenital inner ear anomalies such as Mondini’s dysplasia, enlarged vestibular aqueduct and genetic disease like CHARGE syndrome are predispose to vertigo along with hearing loss 19. The prognosis of the post-traumatic cases with vestibular dysfunction is variable and unpredictable.

Vestibular neuritis

The aetiology of the vestibular neuritis is somewhat controversial; many authors have suggested that is due to viral infections although bacterial and other variety of infections have also been suggested 20. One study found around 47% of the upper respiratory tract infection before the onset of the vestibular neuritis 21. The exact aetiology of vestibular neuritis is controversial, although an association with herpes simplex virus has been found. Pediatric patients suffering from vestibular neuritis often present with similar symptoms as their adult counterparts. Vestibular neuritis is rarely found in children less than 10 years of the age 21. It presents with sudden onset of severe vertigo, nystagmus, nausea and vomiting. This vertigo is worsened by head movements and children or patients usually prefer to lie down, often with the affected ear up. They do not present with hearing loss and tinnitus. Vestibular laboratory investigation shows the unilateral reduced vestibular response to the thermal caloric test. The clinical symptoms of the child will resolve within a few days. The management of this patient includes supportive and symptomatic treatment with early ambulation. A short treatment with vestibular suppressants such as meclizine (≥12 years) or dimenhydrinate (≥2 years) may be prescribed but should be limited as it often delays central compensation 22.

Vestibular paroxysmia (VP)

This is an interesting type of the vestibular entity because of the involvement or compression of the vestibular or eighth cranial nerve also termed as disabling positional vertigo 23. In 1994, Brandt and Dieterich coined the term vestibular paroxysmal 24. Although it is rare in clinical practice, the VP can cause vertigo in the pediatric patient as well. It usually presents frequent episodes of vertigo, multiple times in a day, lasting for seconds to minutes with or without the presence of postural variation. The attacks of vertigo can be up to thirty times or more in a day. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or angiography helps demonstrate the neurovascular compression of the vestibulocochlear nerve and also to rule out cerebellopontine angle tumours 25. In the majority of the cases, vascular lop by anterior inferior cerebellar artery is seen to compress the nerve, however posterior inferior cerebellar artery and vertebral artery or vein are rarely involved. Low dose sodium channel blocker such as carbamazepine is shown to help control vertigo in pediatric age of VP. Micro-vascular decompression is an absolute option for relieving the vestibular symptoms but indicated only in certain cases such as a failed pharmacotherapy, fear of surgical morbidity and difficulty in deciding the size of the lesions.

Meniere’s disease (MD)

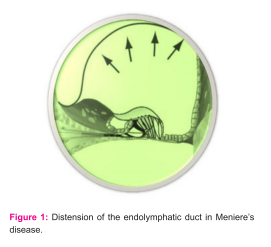

MD is an uncommon disease among the pediatric age group and accounts for <3% of all the MD patients 26. Out of all aetiology for vertigo in the pediatric age group, MD is found in 1.5-4% of pediatric age 27. MD or endolymphatic hydrops (Fig.1) in children present with episodic vertigo, fluctuating deafness, aural fullness and tinnitus. The pure tone audiometry reveals sensorineural hearing loss with the involvement of low-frequency sound. But children often unable to communicate about aural fullness and tinnitus, so MD should not be excluded in case of absence of aural fullness and ringing sound in the ear. The pediatric patients with MD are usually older than 10 years of the age and very few cases have been reported in less than 7 years of age 28. The pathophysiology of MD is associated with allergy both in children and adults and the treatment of the allergy will cure the symptoms of MD. The management of MD in both adults and pediatric patients are similar and include labyrinthine sedatives, low salt diet, intra-tympanic gentamycin and less commonly endolymphatic sac decompression 29.

Middle ear effusion and otitis media

Pediatric patients with vertigo may occur due to middle ear effusion and otitis media. [30] As many pediatric patients with abnormal ventilation of the middle ear cleft do not present vertigo, the symptoms are often presented by their parents who say clumsiness, awkwardness and falling. In case of the middle ear pathologies, the released toxins seen in the middle ear fluid absorbed into the inner ear fluid and lead to serious labyrinthitis 30. Others have proposed that alteration of the pressure in the middle ear cause displacement of the oval window and round windows which move the inner ear fluids 31. One study documented a greater chance of sway in a group of 41 pediatric patients with otitis media in comparison to pediatric patients with no ear disease 32. Similarly, one more study documented that body sway was more pronounced in pediatric patients with otitis media in comparison to the control group. However, the authors also documented that elimination of these by treating otitis media by myringotomy and insertion of the grommet 33.

DIAGNOSIS

Despite significant development of the technology in diagnostic tools, the diagnosis is still based mainly on proper history taking and examination findings. However, the diagnosis of pediatric vertigo differs from the adult age group because of the etiologies are often unique to the vertigo of the children 34. Around 90% of the pediatric patients with vertigo are categorized as “unspecified dizziness”, showing that the diagnostic accuracy and treatment options in the pediatric age group with vertigo should be improved 35. Getting the exact diagnosis of pediatric vertigo can be difficult, specifically in very young pediatric patient whose ability to tell the symptoms is very less. Patience and time are required for the proper diagnosis of pediatric vertigo. Patient history and clinical examinations including otological and neuro-otological examinations help in diagnosis. Patient history has a vital role in the evaluation of vertigo and the diagnosis of vertigo. The pediatric patient often unable to describe the symptoms, so parent’s observation of vertigo should be taken into consideration for diagnosis. Although rare, the child may present with vertigo on exposure to loud noise as in superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome 36. In the pediatric age group, common etiologies for vertigo are benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood(BPVC) and migraine-associated vertigo(MAV), although the frequencies of occurrence vary between different studies 37. The characteristics of the BPVC are brief and recurrent episodes of vertigo in absence of any warning and resolving spontaneously in a normal child 38. The criteria for diagnosis are at least 5 attacks of vertigo along with minimum one of the following: nystagmus, vomiting, ataxia, pallor, fearfulness; in addition to normal audiometric findings, normal examination and vestibular functions in between attacks needed. Seizures, posterior fossa neoplasms and vestibular lesions should be ruled out 38. BPVC has better prognosis as clinical symptoms tend to be absent after six to twelve months 39. In addition to thorough neuro-otologic and systemic examination, vestibular tests like cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potential (cVEMP), posturography, electronystagmography (ENG), rotatory chair test and caloric test. A complete hearing assessment is mandatory in the pediatric patient with vertigo which includes Otoacoustic emissions (OAEs), hearing test or behavioural audiometry, brainstem evoked response audiometry (BERA), auditory steady-state response (ASSR) and impedance audiometry. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred imaging for assessing vertigo in the pediatric age group. Clinicians should advice neuro-imaging studies for children with vertigo who have neurologic signs and symptoms, risk factors of cerebrovascular lesions or progressive unilateral sensorineural hearing loss or tinnitus 40. MRI avoids ionizing radiation of computed tomography (CT) scan and gives a greater sensitivity for posterior fossa and labyrinthine defects 41. The negative aspects of the MRI are cost and requirement of sedation in the pediatric patient. History of head trauma and focal neurological deficit brings up the indication for MRI. Evaluation of the blood pressure and electrocardiography (ECG) is useful to rule out a cardiovascular disease like arrhythmia or long QT syndrome. Diseases of the eye and refractive errors should be ruled out even with a known cause for vertigo, as these may cause worse symptomatology 42.

TREATMENT OF PEDIATRIC VERTIGO

The difficulty and enigma in the treatment of the pediatric vertigo are because it is not a definite disease but a symptom which usually diagnosed late in children. The treatment of vertigo in the pediatric age should be individualized. Based on the aetiology, the treatment includes medications, physical therapy, psychiatric treatment and less commonly surgery. There is still a paucity of documentation on the drug treatment of vertigo even in the current scenario since there have been no multicentric, well-controlled studies to show the advantages of treatment over no treatment 43. The treatment of the vestibular migraine includes watchful waiting and education of the children of vertigo and their parents in addition to stress reduction, encouragement for adequate sleep, psychological counselling, rehabilitation therapy if required as well as dietary restrictions of foods own to provoke. Medical treatment of vestibular migraine includes simple analgesic and/or vestibular suppressant such as meclizine during the attack. In children with benign paroxysmal vertigo, vestibular suppressants are usually not very useful due to the very short duration of the attack. In vestibular neuritis, vestibular rehabilitation and corticosteroids are often helpful and facilitate recovery of the disease, particularly when prescribed initial period of the disease. Ophthalmological evaluation and correction are also important as visual problems can lead to vertigo or dizziness. Management of the Meniere’s disease in pediatric age is reassurance and explanations of this condition to the caregivers along with low salt diet and a diuretic 28. The requirement of surgery in pediatric Meniere’s disease is uncommon.

CONCLUSION

Vertigo in the pediatric age group has myriad of clinical presentations and possible diagnoses. The aetiology of vertigo in the pediatric age group is often multi-factorial, so a pediatric patient is approached with an open mind. A thorough evaluation of vertigo in children though difficult is mandatory. Disorders that cause vertigo in the pediatric age group vary concerning one another in many ways. The peripheral vestibular disorders rarely cause symptoms lasting more than a few minutes although Meniere’s disease and vestibular neuritis lasting for hours. Vestibular migraine causes symptoms lasting for virtually any duration. Vertigo in children can be highly challenging for evaluation and treatment. Relying on vestibular tests alone may cause misleading of the diagnosis. The physicians must judiciously utilize all the diagnostic modalities at his/her disposal before dismissing less commonly encountered diagnosis.

References:

1.Moulin T, Sablot D, Vidry E, Belahsen F, Berger E, Lemounaud P, et al. Impact of emergency room neurologists on patient management and outcome. Eur Neurol 2003; 50:207-14.

2. Swain SK, Baliarsingh D, Sahu MC. Vertigo among elderly people: Our experiences at a tertiary care teaching hospital of eastern India. Annals of Indian Academy of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2018; 2(1):1-5.

3.Swain SK, Behera IC, Das A, Sahu MC. Prevalence of Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: Our experiences at a tertiary care hospital of India. Egyptian Journal of ear, nose, throat and allied sciences2018;19(3):87-92.

4.Niemensivu R, Pyykkö I, Wiener-Vacher SR, Kentala E. Vertigo and balance problems in the children-an epidemiologic study in Finland. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology2006;70(2):259-65.

5.Riina N, Iimari P, Kentala E. Vertigo and imbalance in children: a retrospective study in a Helsinki University Otorhinolaryngology clinic 2005;131:996-1000.

6. Abu-Arafeh I, Russell G. Paroxysmal vertigo as a migraine equivalent in children: a population-based study. Cephalagia1995; 15: 22-5.

7.Royal College of Physicians, Hearing and balance disorders: achieving excellence in diagnosis and management. Report of a Working Party. London, RCP,2008.

8.Weiner-Vacher S. Vestibular disorders in children. Int J Audiol 2008;47:578-83.

9.Neuhauser H, Lempert T. Vestibular migraine. Neurol Clin2009;27:379-91.

10.Cutter FM, Baloh RW.Migraine associated dizziness.Headache 1992;32:300-4.

11. Ralli G, Atturo F, de Filippis C. Idiopathic benign paroxysmal vertigo in children, a migraine precursor. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2009; 73 (1):16-18.

12. Balatsouras DG, Kaberos A, Assimakopoulos D, Katotomichelakisc M, Economou NC, Korres SG. Aetiology of vertigo in children. Int J Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol2007; 71:487-94.

13.McCaslin DL, Jacobson GP, Gruenwald JM. The predominant forms of vertigo in children and their associated findings on balance function testing. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2011; 44 (2):291-307.

14.Koenigsberger MR, A.M. Chutorian AM, Gold AP, Schvey MS. Benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood. Neurology1968; 18 (3):301-2.

15. Eviatar L, Bergtraum M, Randel RM. Post-traumatic vertigo in children: a diagnostic approach. Pediatric neurology1986;2(2):61-6.

16.Kim SH, Kazahaya K, Handler SD. Traumatic perilymphatic fistulas in children: aetiology, diagnosis and management. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology2001;60(2):147-53.

17.Neuenschwander MC, Deutsch ES, Cornetta A, Willcox TO. Penetrating middle ear trauma: a report of 2 cases. Ear, nose & throat journal2005;84(1):32-5.

18.Vartiainen E, Karjalainen S, Kärjä J. Vestibular disorders following head injury in children. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology1985;9(2):135-41.

19. Chiarella G, Viola P. The challenge of pediatric vertigo. J Ear Nose Throat Disord 2017;2(3):1027.

20.Strupp M, Brandt T. Vestibular neuritis. Semin Neurol2009; 29 (5): 509-19.

21. Taborelli G, Melagrana A, D'Agostino R, Tarantino V, Calevo MG. Vestibular neuronitis in children: study of medium and long term follow-up. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 2000;54(2-3):117-21.

22. Li CM, Hoffman HJ, Ward BK, Cohen HS, Rine RM. Epidemiology of dizziness and balance problems in children in the United States: a population-based study. The Journal of paediatrics 2016;171:240-7.

23. PJ J. Møller MB. Møller AR: Disabling positional vertigo. N Engl J Med1984;310:1700-5.

24. Brandt T, Dieterich M. Vestibular paroxysmal: vascular compression of the eighth nerve?. The Lancet 1994;343(8900):798-9.

25. Best C, Gawehn J, Krämer HH, Thömke F, Ibis T, Müller-Forell W, et al. MRI and neurophysiology in vestibular paroxysmia: contradiction and correlation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013;84(12):1349-56.

26. Meyerhoff WL, Paparella MM, Shea D. Meniere's disease in children. The Laryngoscope. 1978;88(9):1504-11.

27. Gioacchini FM, Alicandri-Ciufelli M, Kaleci S, Magliulo G, Re M. Prevalence and diagnosis of vestibular disorders in children: a review. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 2014;78(5):718-24.

28. Brantberg K, Duan M, Falahat B. Ménière's disease in children aged 4–7 years. Acta oto-laryngological. 2012;132(5):505-9.

29. Meyerhoff WL, Paparella MM, Shea D. Meniere's disease in children. The Laryngoscope1978;88(9):1504-11.

30. Golz A, Netzer A, Angel-Yeger B, Westerman ST, Gilbert LM, Joachims HZ. Effects of middle ear effusion on the vestibular system in children. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery1998;119(6):695-9.

31. Suzuki M, Kitano H, Yazawa Y, Kitajima K. Involvement of round and oval windows in the vestibular response to pressure changes in the middle ear of guinea pigs. Acta oto-laryngologica1998;118(5):712-6.

32. Casselbrant ML, Rubenstein E, Furman JM, Mandel EM. Effect of otitis media on the vestibular system in children. Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology 1995 ;104(8):620-4.

33. Jones NS, Prichard AJ, Radomskij P, Snashall SE. Imbalance and chronic secretory otitis media in children: effect of myringotomy and insertion of ventilation tubes on body sway. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology1990; 99(6):477-81.

34. Gruber M, Cohen-Kerem R, Kaminer M, Shupak A. Vertigo in children and adolescents: characteristics and outcome. The Scientific World Journal 2012;2012.Article ID 109624.

35.O’Reilly RC, Morlet T, Nicholas BD, Josephson G, Horlbeck D, Lundy L, et al. Prevalence of vestibular and balance disorders in children. Otol Neurotol 2010;31:1441-4.

36.Swain SK, Das A, Sahu MC. Superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome: An uncommon cause of vertigo.Archives of Medicine and Health Sciences 2018;6(2):262.

37.Langenhagen T, Schroeder AS, Rettinger N, Borggraefe I, Jahn K. migraine-related vertigo and somatoform vertigo frequently occur in children and are often associated. Neuropediatrics 2013 ;44(1):55-8.

38. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013;33(9):629-808.

39.Youssef PE, Mack KJ. Episodic and chronic migraine in children. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2020 ;62(1):34-41.

40.Drachman DA.A 69-year-old man with chronic dizziness.JAMA1998;280:2111-18.

41.Loevner LA. Imaging features of posterior fossa neoplasms in children and adults. Semin Roentgenol 1999;34(2):84-101.

42.Erbek SH, Erbek SS, Yilmaz I, Topal O, Ozgirgin N, Ozluoglu LN, et al. Vertigo in childhood: a clinical experience. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2006;70(9):1547-54.

43.Ruckenstein M, Rutka J, Hawke M.The treatment of Meinere disease: Torok revisited.Laryngoscope 1991;101:211-14.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License