IJCRR - 9(7), April, 2017

Pages: 33-38

Date of Publication: 11-Apr-2017

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

Anthropometric Characteristics and Body Composition of the Rural and Urban Children

Author: Kanwar Mandeep Singh, Mandeep Singh, Karanjit Singh

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Aim: The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the anthropometric characteristics and body composition components of the rural and urban children from Punjab.

Methodology: Total 360 children (180 rural and 180 urban) of age between 12 to 18 years were selected to participate in the study. Height of the subjects was measured with the stadiometer. Body mass was assessed by using the portable weighing machine. Widths and diameters of body parts were measured by using digital caliper. Girths and lengths were taken with the flexible steel tape. Skinfold thicknesses were measured with the help of Harpenden skinfold caliper.

Results: The results revealed that the rural children were significantly taller (p< 0.01) and heavier (p< 0.01) than the urban children. Body mass index was significantly higher (p< 0.05) in rural children as compared to urban children. The rural children also had significantly greater length measurements (p< 0.01), circumferences (p< 0.01) and diameters (p< 0.01) in comparison to urban children. The rural children possessed significantly higher lean body mass (p< 0.01) than the urban children.

Conclusion: In conclusion, it is evident from the results that place of residence had impact on the anthropometric characteristics among the children.

Keywords: Anthropometric Measurements, Rural, Urban, Children, Percent body Fat

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Human settlements are categorized as rural or urban areas on the basis of the density of population and human formed structures in a particular area. Urban areas consist of towns and cities while rural areas contain villages and hamlets. Rural areas may develop randomly on the foundation of natural vegetation and fauna available in a region, whereas urban settlements are proper, suitable and planned settlements developed according to a process called urbanization. The urbanization process takes place in various countries under different circumstances in recent times (Valladares and Coelho, 1993). The differences in growth, body dimensions, body composition and fitness levels of children due to urban and rural environmental disparities have come into center of attention during the last few years.

Nowadays studies are conducted to examine the evolutionary importance of differences in anthropometric characteristics, body proportions and body composition between populations whose ancestors lived in different environmental settings. Many research studies in the human biological literature investigated the differences in urban and rural populations and in different socio-economic strata with regard to anthropometric characteristics. Height, weight and other body dimensions are differed in rural and urban children and in children from different socio-economic groups in nearly all the developed and in developing countries. Many studies have reported that physical parameters related to growth and development in urban children was at higher level than in rural children (ICMR, 1972; Phadake, 1968; Sahoo et al, 2011). There are several studies from Europe in the past 100 years show that urban children have greater body dimensions and mature earlier compared to children living in rural areas and urban and rural differences are existed among adults in many countries (Bielicki, 1986). The greater anthropometric characteristics among urban children are attributed to advantageous transformations in health and diet and in wide-ranging living circumstances related to urbanization. The differences among urban and rural children are exaggerated by unending dietary problems in the rural areas and noticeable economic disparities in many African, Asian and Latin American countries. In the more developed countries of these continents, the greater anthropometric characteristics and earlier growth and development of children living in urban areas reveal the advantageous outcomes of urbanization related with enhanced economic status and access to facilities (Eveleth and Tanner, 1990). There is little agreement from published comparisons of urban and rural children with regard to anthropometric measurements. A study of children in Crete (Mamalakis et al, 2000) found higher skinfolds among urban children, while higher levels of body fat have been reported in rural Belgian (Guillaume et al, 1997) and North American (McMurray et al, 1999) youth. A Polish study (Wilczewski et al, 1996) reported lower skinfolds in rural boys compared with urban boys but no differences for girls. Booth et al (1999) found no differences between urban and rural children with regard to body mass index and skinfolds in New South Wales. Henneberg and Louw (1998) reported that urban South African children had greater height, weight and skinfold thickness than their rural counterparts. Arm muscle area and waist/hip ratio were higher among rural adolescents compared to urban adolescents in the Cameroon (Dapi et al, 2005). Aberle et al (2009) found no differences in anthropometric characteristics between rural and urban children in Croatia. Greater height and lower body mass index were reported among rural Vietnamese children compared to their urban counterparts (Dang et al, 2010). Mesa et al (1996) reported no significant differences in percent body fat, lean body mass and sum of skinfolds between rural and urban children in central Spain. In a study on Kenyan children, Adamo et al (2010) reported that none of rural children were overweight or obese and they had lower body mass index, waist circumference and triceps skinfold than urban children. Body mass index and skinfolds thickness were higher among urban children in Turkey (Ozdirenc et al, 2005; Tinazci and Emiroglu, 2008; Tinazci Emiroglu, 2009). Urban children in Oman had higher percentage of body fat and body mass index compared to their rural counterparts (Albarwani et al, 2009; Al-Shamli, 2010).

Genetic endowments influence the growth and maturation process can better evident under better environmental conditions. In the growth studies, the effects of socioeconomic factors and rural and urban environment are related. In the present study, the attempt has been made to study the differences (if any) in anthropometric characteristics and body composition with regard to place of residence among children from Punjab, India.

METHODOLOGY

The subjects of the present study were selected from the camps organized under “Catch Them Young Programme” by Department of Physical Education (AT), Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar. A total 360 children, aged 12-17 years, from the various districts of Punjab viz. Amritsar, Jalandhar, Tarn-taran, Kapurthala, Nawashehar and Gurdaspur were purposively selected to participate in the study. Out of 360 male children, 180 children were from rural areas and 180 children were belonged to the urban areas. The meaning and definition of rural and urban residence is differing in different studies and countries according to their country norms. An area with a minimum population of 15,000, with 75 percent of the male population is engaged in non-agricultural works is considered as urban area tn the present study.

Anthropometry

Standing height of the subjects was measured using a Stadiometer, with the subject’s shoes off and head in the Frankfort horizontal plane. Body mass of the subjects was assessed by using the portable weighing machine. Diameters of body parts of the subjects were measured by using digital sliding caliper. Circumferences and length measurements of body parts of the subjects were taken with the flexible steel tape. Skinfold thicknesses of the subjects were measured with the help of Harpenden skinfold caliper.

Body Mass Index

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by the following formulae

BMI (Kg/m2) = (Body mass in Kg)/(Stature in Meters)2

(Meltzer et al., 1988)

Percent Body Fat

Percentage body fat as estimated from the sum of skinfolds was calculated using equations of Slaughter et al (1988).

Percent Body Fat = 1.21(triceps+subscapular)x0.008(triceps+subscapular)x2-1.7

Total Body Fat (kg) = (%body fat/100) ´ body mass (kg)

Lean body mass (LBM) was calculated using the % body fat value estimated from the sum of skinfolds.

Lean Body Mass (kg) = body mass (kg) – total body fat (kg)

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 16.0 for windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). All descriptive data pertaining to anthropometric measurements and body composition variables was reported as mean and standard deviation. An independent sample t-test was used to compare the mean values of anthropometric measurements and body composition variables between rural and urban boys. Significance levels were set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

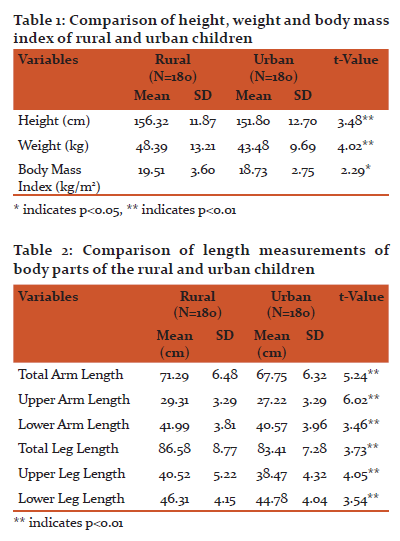

The height, weight and body mass index of the rural and urban children is given in table 1. The rural children were significantly taller (t = 3.48, p < 0.01) as compared to their urban counterparts. The rural boys children also significantly heavier (t = 4.02, p < 0.01) than the urban children. Similarly, the rural children were reported to have significantly greater body mass index (t = 2.29, p < 0.05) as compared to children residing in the urban areas.

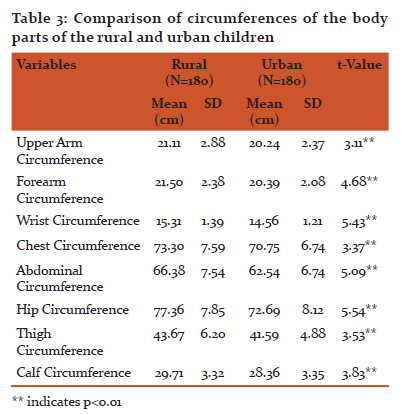

The table 2 presents the length measurements of body parts of the rural and urban children. The rural children were found to have significantly greater total arm length (t = 5.24, p < 0.01) when compared to their urban counterparts. The rural children were also reported to have significantly greater upper arm length (t = 6.02, p < 0.01) and lower arm length (t = 3.46, p < 0.01) than the children living in urban areas. Similarly, the children from rural areas had significantly greater total leg length (t = 3.73, p < 0.01), upper leg length (t = 4.05, p < 0.01) and lower leg length (t = 3.54, p < 0.01) than the children residing in urban areas.

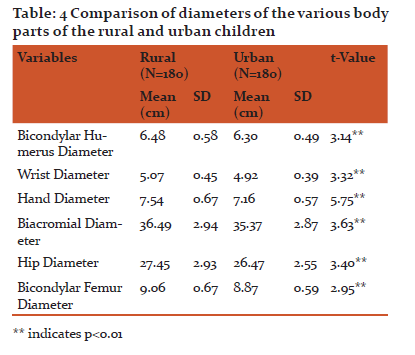

The table 3 presents the various circumferences of body parts of the rural and urban children. The rural children were found to have significantly greater upper arm circumference (t = 3.11, p < 0.01), forearm circumference (t = 4.68, p < 0.01) and wrist circumference (t = 5.43, p < 0.01) when compared to their urban counterparts. The rural children were also reported to have significantly greater chest (t = 3.37, p < 0.01), abdominal (t = 5.09, p < 0.01) and hip (t = 5.54, p < 0.01) circumferences than the children living in urban areas. Similarly, the children from rural areas had significantly greater thigh (t = 3.53, p < 0.01) and calf (t = 3.83, p < 0.01) circumferences than the children residing in urban areas.

The various diameters of body parts of the rural and urban children are given in table 4. The rural children were found to have significantly greater bicondylar humerus diameter (t = 3.14, p < 0.01) as compared to their urban counterparts. The rural children were also reported to have significantly greater wrist (t = 3.32, p < 0.01), hand (t = 5.75, p < 0.01) and biacromial (t = 3.63, p < 0.01) diameters than the children living in urban areas. Similarly, the children from rural areas had significantly greater hip (t = 3.40, p < 0.01) and bicondylar femur (t = 2.95, p < 0.01) diameters than the children residing in urban areas.

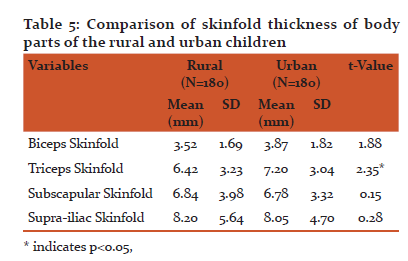

The table 5 depicts the skinfold thicknesses of the body parts of the rural and urban children. There was no significant difference in relation to biceps skinfod thickness between the rural and urban children. The urban children were found to have significantly greater triceps skinfold thickness (t = 2.35, p < 0.05) as compared to their rural counterparts. Whereas, in case of subscapular and supra-iliac skinfold thicknesses, there were no significant differences between rural and urban children.

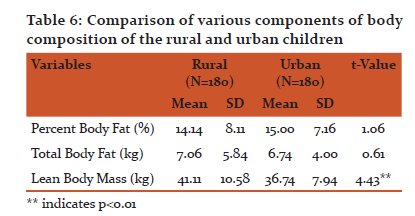

The various components of body composition of the body parts of the rural and urban children are shown in table 6. There was no significant difference in relation to percent body fat and total body fat between the rural and urban children. On the other hand, the rural children were found to have significantly greater lean body mass (t = 4.43, p < 0.01) as compared to their urban counterparts.

DISCUSSION

The principle aim of the current study was to examine potential differences in anthropometric measurements and body composition of Punjabi boys living in either urban or rural settings. The main findings were that rural children had significantly higher values on the most of the parameters than their urban counterparts. The rural children were significantly heavier and taller than urban children. These results are in conformity with various studies published on the children of the Punjab (Kaur and Singh, 2010). Matsuura et al, (1974) reported similar findings on Thai and Indonesian children. But the present data do not agree with the reports published on children in other states of India which reported greater height and weight among the urban children than the rural children (Bharati et al, 2005; Kolekar and Sawant, 2013; Khan et al, 1990; Adak et al, 2002). Similarly the findings of the present study are not in line with various studies reported on children in other countries. It has been found that Hungarian, Brazilian, Spanish, Greek and Mexico urban children have greater height and weight than their rural counterparts (Mazzuco et al. 2006, Eiben et al. 2005, Pena Reyes et al. 2003; Chillon et al. 2011; Mesa et al, 1996; Tambalis et al, 2010). In line with the previously published reports on Indian children (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2005, Venkaiah et al. 2002) the present data demonstrated that children of Punjab from both rural and urban areas have higher height and body weight than the rural Indian boys and urban Bengalese boys. In the present study the rural children had significantly greater body mass index as compared to urban children. These results are in conformity with the results reported by Ramachandran et al (2009) on Kerala boys and Tambalis et al (2010) on Greek children. But the findings of the present study are not in agreement with studies reported on children in many countries (Booth et al, 1999; Aberle et al, 2009; Adamo et al, 2010; Ozdirenc et al, 2005; Tinazci and Emiroglu, 2008; Tinazci and Emiroglu, 2009; Albarwani et al, 2009; Pena Reyes et al. 2003; Dana et al, 2011; Ujevic et al, 2013). The body mass index of children in present study was higher than those among urban children of Kolkata reported by de Onis et al (2001) and Bengalese boys studied by Chatterjee et al (2006). But the subjects in the present study have lower body mass index than the Swedish children (Orjan et al. 2005). The rural boys were reported to have significantly greater length measurements of body parts than the urban boys. The results are in conformity with those of reported by Singh and Bhola (2012) on rural and urban children in Haryana. But these findings are not in agreement with those of Henneberg and Louw (1998) who reported that the urban children had better length of body segments than the rural children in Cape Town. Masturra et al (1974) also reported that Japanese, Thai and Indonesian urban boys had greater leg length than the rural boys. The results revealed that the rural boys had significantly greater circumferences and diameters of the body parts than the urban boys. Similar findings are reported by many studies in literature (Adak et al, 2002; Singh and Bhola, 2012). In contrast, Booth et al (1999) reported that there were no differences in rural and urban New South Wales children. Bharati et al (2005) reported better circumferences in the urban children from Raichur region of India. Eiben et al (2005) compared the Hungarian Children from rural and urban settings and reported that urban children had better diameters of body parts than their rural counterparts. Adamo et al (2010) also found that the urban children had greater circumferences than the rural children from Kenya. There were no significant differences in skinfold thicknesses between rural and urban boys except for triceps skinfold thickness. Similar results are reported by Ozdirenc et al, (2005) and Tinazci and Emiroglu (2008) on Turkish children, Dollman et al (2002) on Australian children, Ramachandran et al (2009) on Kerala children. In body composition, no significant differences were reported for percent body fat and total body fat among the rural and urban boys. Similar findings are reported by Ujevic et al (2013) on the Croatian children. But Kangane and More (2013) reported contrasting findings on Maharashtra children in which rural boys had significantly higher percent body fat than the urban boys. Vyas et al (2012) also reported that rural boys had higher percent body fat than the city boys in Gandhinagar. However, the urban children showed higher percent body fat than their rural counterparts in Greece, Oman, Turkey and Bengal (Tsimeas et al, 2005; Al-Shamli, 2010; Saha and Haldar, 2012; Ozdirenc et al, 2005). The rural boys were possessed significantly greater muscle mass than their urban counterparts. This might be due to fact that the rural boys have more activity oriented environment and more physical workload due to engagement in agriculture related works. The results of present study are not in line with those reported by Mesa et al (1996) on the Spanish children with regard to the body composition which showed no significant differences in lean body mass between rural and urban children.

CONCLUSION

It is concluded that the place of residence has clear impact on anthropometric measurements and body composition of children as studied herein. The way of life and food habits and the constituents of food might have played significant role in the differences among children from different settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Authors acknowledge the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. The authors are also grateful to authors/editors/publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed. Authors also acknowledge the cooperation of subjects during the data collection.

References:

- Aberle, N., Blekic, M., Ivanis, A. and Pavlovic, I. (2009). The comparison of anthropometrical parameters of the four-year-old children in the urban and rural Slavonia, Croatia, 1985 and 2005. Collegium Antropologicum, 32(2):447-451.

- Adak, D.K., Tiwari, M.K., Randhawa, M., Bharati, S. and Bharati, P. (2002). Pattern of adolescent growth among the brahmin girls: rural-urban variation. Collegium Antropologicum, 26(2): 501–507.

- Adamo, K.B., Sheel. A.W., Onywera, V., Waudo, J., Boit, M. and Tremblay, M.S. (2010). Child obesity and fitness levels among Kenyan and Canadian children from urban and rural environments: A KIDS-CAN Research Alliance Study. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 1–8.

- Albarwani, S., Al-Hashmi, K., Al-Abri, M., Jaju, D. and Hassan, M.O. (2009). Effects of overweight and leisure-time activities on aerobic fitness in urban and rural adolescents. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders, 7:369–374.

- Al-Shamli, A. (2010). Physical activity and physiological fitness status of 10th grade male students in Al-Dhahirah region, Sultanate of Oman. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences 2(2):99-109.

- Bharati, P., Itagi, S., and Megeri, S.N. (2005) Anthropometric measurements of school children of Raichur, (Karnataka). Journal of Human Ecology, 18(3):177-179.

- Bielicki, T. (1986). Physical growth as a measure of economic well-being of populations: The twentieth century. In F Falkner and JM Tanner, eds.: Human Growth. A Comprehensive Treatise, Vol 3. Plenum Press, New York. pp: 283-305.

- Booth, M.L., Macaskill, P., Lazarus, R. and Baur, L.A. (1999). Socio demographic distribution of measures of body fatness among children and adolescents in New South Wales, Australia. International Journal of Obesity, 23:456–472.

- Chatterjee, S., Chatterjee, P. and Bandyopadhyay, A. (2006). Skinfold thickness, body fat percentage and body mass index in obese and non-obese Indian boys. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 15 (2):231-235.

- Chillon, P., Ortega, F.B., Ferrando, J.A. and Casajus, J.A. (2011). Physical fitness in rural and urban children and adolescents from Spain. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 4(5):417-23.

- Dana, A., Habibi, Z., Hashemi, M. and Asghari, A. (2011). A description and comparison of anthropometrical and physical fitness characteristics in urban and rural 7-11 years old boys and girls in Golestan Province, Iran. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 8(1):231-236.

- Dang, C.V., Day, R.S., Selwyn, B., Maldonado, Y.M., Nguyen, K.C., Danh, T. and Le, M.B. (2010) Initiating BMI prevalence studies in Vietnamese children: changes in a transitional economy. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 19(2):209-216.

- Dapi, L.N., Nouedoui, C., Janlert, U. and Glin, L.N. (2005). Adolescents food habits and nutritional status in urban and rural areas in Cameroon, Africa. Scandinavian Journal of Nutrition, 49(4):151-158.

- de Onis, M., Dasgupta, P., Saha, S., Sengupta, D. and Blossner, M.T (2001). The National Center for Health Statistics reference and the growth of Indian adolescent boys. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 74:248-253.

- Dollman, J., Norton, K. and Tucker, G. (2002). Anthropometry, fitness and physical activity of urban and rural south Australian children. Pediatric Exercise Science, 14:297-312.

- Eiben, O.G., Barabas, A. and Nemeth, A. (2005). Comparison of growth, maturation, and physical fitness of Hungarian urban and rural boys and girls. Journal of Human Ecology, 17(2):93-100.

- Eveleth, P.B. and Tanner, J.M. (1990). Worldwide variation in human growth. Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition, Cambridge.

- Guillaume, M., Lapidus, L., Bjornstorp, P. and Lambert, A (1997). Physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular risk factors in children: The Belgian Luxembourg Child Study II. Obesity Research, 5:549-556.

- Henneberg, M. and Louw, G.J. (1998). Cross-sectional survey of growth of urban and rural ‘Cape Coloured’ schoolchildren: Anthropometry and functional tests. American Journal of Human Biology, 10:73-85.

- ICMR, (1972). Growth and physical development of Indian infants and children. Technical Report Series No 18, New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research.

- Kangane, S. and More, S. (2013). Study on percentage body fat of 13 years school going boys in Nashik district. Variorum Multi-Disciplinary e-Research Journal, 4(2):1-3.

- Kaur, B. and Singh, G. (2010). A comparative study of anthropometric characteristics and motor abilities between urban and rural sports girls. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(Suppl I):i39.

- Khan, A.Z., Singh, N.I., Hasan, S.B., Sinha, S.N. and Zaheer, M. (1990). Anthropometric measurements in rural school children. Journal of Rural Social Health, 110(5):184-186.

- Kolekar, S.M. and Sawant, S.U. (2013). A comparative study of physical growth in urban and rural school children from 5 to 13 years of age. International Journal of Recent Trends in Science and Technology, 6(2):89-93.

- Mamalakis, G., Kafatos, A., Manios, Y., Anagnostopoulou, T. and Apostolaki, I. (2000). Obesity indices in a cohort of primary school children in Crete: a six year prospective study. International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders, 24(6):765-771.

- Matsuura, Y., Ohyama, Y. and Murai, A. (1974). A comparative study on physical fitness of children of three nations; Japanese, Thai and Indonesia. Southeast Asian Studies, 12(3):383-400.

- Mazzuco, M., Siqueira, A. and Giana S. (2006). Differences in anthropometrical and fitness variables among male students from Brazilian urban and rural schools. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 38(5): S214-S215.

- McMurray, R.G., Harrell, J.S., Bangdiwala, S.I., et al. (1999). Cardiovascular disease risk factors and obesity of rural and urban elementary school children. Journal of Rural Health, 15:365–74.

- Meltzer, A., Muller, W., Annegers, J., Grines, B. and Albright, D. (1988). Weight history and hypertension. Clinical Epidermiology, 41:867-874.

- Mesa, M.S., Sanchez-Andres, A., Marrodan, M.D., Martin, J. and Fuster, V. (1996). Body composition of rural and urban children from the central region of Spain. Annals of Human Biology, 23(3):203-212.

- Mukhopadhyay ,A., Bhadra, M. and Bose, K. (2005). Physical exercise, body mass index, subcutaneous adiposity and body composition among Bangalee boys aged 10-17 years of Kolkata, India. Anthropologischer Anzeiger; Berichtuber die biologisch- anthropologische Literature, 63(1): 93-101.

- Orjan, E., Kristjan, O. and Bjorn, E. (2005). Physical performance and body mass index in Swedish children and adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Nutrition, 49(4):172-179.

- Ozdirenc, M., Ozcan, A., Akin, F. and Gelecek, N. (2005). Physical fitness in rural children compared with urban children in Turkey. Pediatrics International, 47(1):26-31.

- Pena Reyes, M.E., Tan, S.K. and Malina, R.M. (2003). Urban–rural contrasts in the physical fitness of school children in Oaxaca, Mexico. American Journal of Human Biology, 15:800–813.

- Phadake, M.V. (1968). Growth norms in Indian children. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 56, 851.

- Ramachandran, A., Deol, N.S. and Gill, M. (2009). Assessment of body mass index and health related fitness among school children. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 25(4):1-6.

- Saha, G.C. and Haldar, S. (2012). Comparison of health related physical fitness variables and psychomotor ability between rural and urban school going children. Journal of Exercise Science and Physiotherapy, 8(2):105-108.

- Sahoo, K., Hunshal, S. and Itagi, S. (2011). Physical growth of school girls from Dharwad and Khurda districts of Karnataka. Karnataka Journal Agricultural Science, 24(2):221-226.

- Singh, B. and Bhola, G. (2012). Comparison of selected anthropometric measurements and physical fitness of Haryana school boys in relation to their social status. Indian Journal of Movement Education and Exercises Sciences, 2(2):

- Slaughter, M.H., Lohman, T.G., Boileau, R.A., Horswill, C.A., Stillman, R.J., Van Loan, M.D. and Bemben, D.A. (1988). Skinfold equations for estimation of body fatness in children and youth. Human Biology, 60:709-723.

- Tambalis, K.D., Panagiotakos, D.B. and Sidossis, L.S. (2010). Greek children living in rural areas are heavier but fitter compared to their urban counterparts: A comparative, time-series (1997-2008) analysis. The Journal of Rural Health, 00:1–8.

- Tinazci, C. and Emiroglu, O. (2008) Assessment of physical fitness levels, gender and age differences of rural and urban elementary school children. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences, 30(1):1-7.

- Tinazci, C. and Emiroglu, O. (2009). Physical fitness of rural children compared with urban children in North Cyprus: a normative study. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 6: 88-92.

- Tsimeas, P.D., Tsiokanos, A.L., Koutedakis, Y., Tsigilis, N. and Kellis, S. (2005). Does living in urban or rural settings affect aspects of physical fitness in children? An allometric approach. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 39(9):671-674.

- Ujevic, T., Sporis, G., Milanovic, Z., Pantelic, S. and Neljak, B. (2013). Differences between health-related physical fitness profiles of Croatian children in urban and rural areas. Collegium Antropologicum, 37:75-80.

- Valladares, I. and Coelho, M. (1993). Urban research in Latin America: toward a research agenda. Disscussion paper series No. 4 (http://www. unesco.org/ most/valleng.htm).

- Venkaiah, K. et al. (2002). Diet and nutritional status of rural adolescents in India. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 56:1119-1125.

- Vyas, M.R., Thakur, S.J. and Parmar, P.P. (2012). Comparative study of body composition between city and rural area boys in Gandhinagar. Journal of Exercise Science and Physiotherapy, 8(1):48-50.

- Wilczewski, A., Sklad, M., Krawczyk, B., et al. (1996). Physical development and fitness of children from urban and rural areas as determined by EUROFIT test battery. Biology of Sport Warsaw, 13:113–26.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License