IJCRR - 10(10), May, 2018

Pages: 39-45

Date of Publication: 30-May-2018

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

Seroepidemiology of Equine Brucellosis and Role of Horse Carcass Processors in Spread of Brucella Infection in Enugu State, Nigeria

Author: Emmanuel Okechukwu Njoga, Joseph Ikechukwu Onunkwo, Samuel Okezie Ekere, Ugochinyere Juliet Njoga, Okoro Winifred N.

Category: Healthcare

Abstract: Aim: The study was undertaken to obtain baseline data on seroepidemiology of equine brucellosis and role of horse carcass processors in spread of Brucella infection in Enugu State.

Materials and Methods: Rose Bengal plate test was used to screen for presence of Brucella antibody in 402 horses slaughtered for human consumption in the State. Structured and pretested questionnaire was used to obtain information on socioeconomic characteristics and involvement of 94 randomly selected horse carcass processors in slaughterhouse practices that facilitate spread of Brucella infection during slaughterhouse operations.

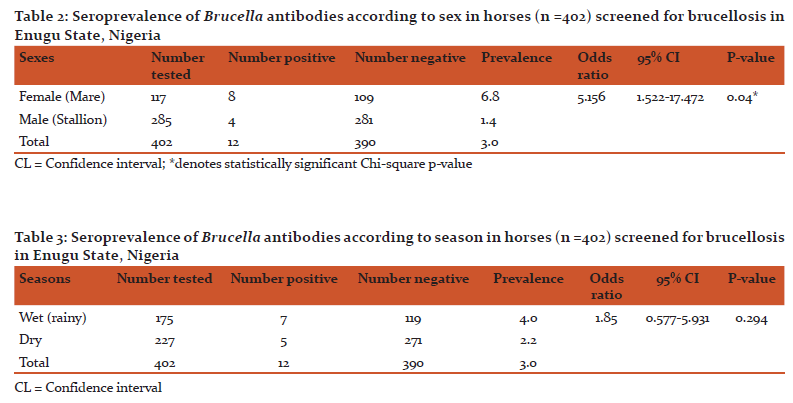

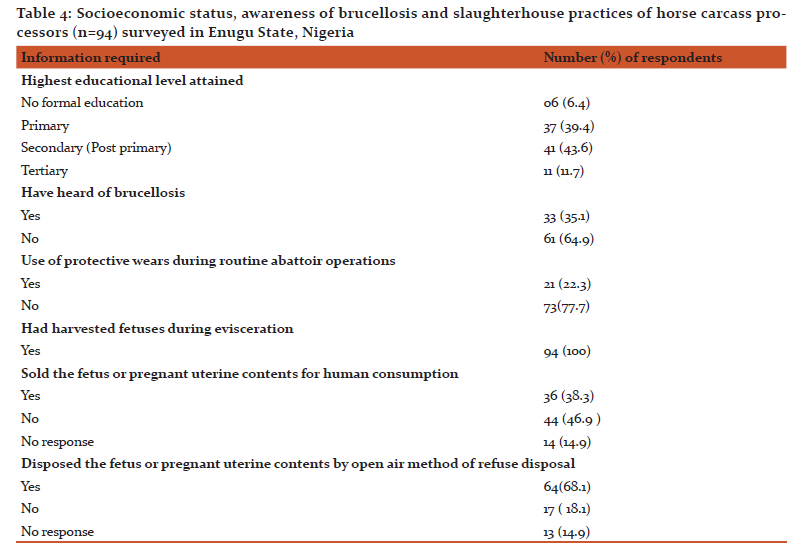

Results: An overall seroprevalence of 3% (12/402) was recorded. Seroprevalence of 8.8 %, 2.1% and 1.9% were obtained from young (1-5 years), adult (6-12 years) and old (>12 years) horses respectively. Similarly, seroprevalence of 6.8% and 1.4% were recorded for females and males respectively while 4% and 2.2% seroprevalence were documented during the rainy and dry seasons respectively. Significant association (p < 0.05) was found between Brucella seropositivity and age and sex. Slaughterhouse practices facilitating dissemination of Brucella infections identified among horse carcass processors and the percentage of the processors involved were: non-use of protective wears during abattoir operations (77.7%), sale of horse fetuses or pregnant uterine contents for human consumption (38.3%) and discharge of eviscerated fetuses or gravid uterine tissues by open dump method of waste disposal (68.1%).

Conclusion: Although the 3% seroprevalence is low, establishment of brucellosis control programme in Enugu State is imperative to avert devastating public health and economic consequences of brucellosis in animal and human populations.

Keywords: Brucellosis, Brucella antibodies, Horses, Risk factors, Nigeria

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

The domestic horse (Equus caballus is an odd-toed (perissodactyla) ungulate mammal belonging to the Equidae family, made up of horses, asses and zebras. In Nigeria, horses are treasured animals used for diverse purposes such as draft, transport, sports, exhibitions, research, recreation, security, crowd control, food (meat and milk), ceremonial and religious festivals, as well as source of variety of products and medicines [1]. In addition, horses are used in rural parts of northern Nigeria, for shepherding ruminants by nomadic herdsmen [2]. The multipurpose use of horse makes them very important in the epidemiology of transmission of Brucella infection at both the animal-animal and animal-human interfaces.

Brucellosis caused by bacteria of the genus Brucella is an important zoonosis ravaging most parts of the world especially the tropics. Although many Brucella species have been described, B. abortus, B. melitensis and B. suis are the principal agents responsible for more than 90% of brucellosis burden globally [3]; preferentially infecting cattle, goats and pigs respectively [4]. Despite their distinct host preferences, these agents can under favorable conditions cause brucellosis of varying degree in most terrestrial animals and humans [4]. Equine brucellosis is caused mainly by B. abortus and to a lesser extent by B. suis biovar 3 and B. melitensis [5]. Horses usually acquire Brucella infection orally by licking vaginal or prepucial discharges from infected animals [6], generally via coitus or use of infected semen for artificial insemination [7], via inhalation of aerosolized Brucella agents in overstocked stables [8], through lactation by an infected dam [9] and by direct or indirect wound contamination with infected tissues and fluids [7, 10].

Brucellosis in horses is characterized by a clinical manifestation called “poll-evil” or “fistulous withers”[1]. This lesion results from the inflammation of supraspinous or supra-atlantal bursa and the associated connective tissue; leading to pus formation and fistulation of the affected parts of the body[1, 10]. Other signs and symptoms of the disease include middle or late term “abortion storm” due to Brucella invasion of the developing fetus and gravid uterus structures[9]; birth of weak/unthrifty foals, retained placenta, neonatal losses and un-thriftiness, repeat breeder syndrome, increased foaling interval, lameness due to polyarthritis, carpal bursitis, orchitis and epididymitis in stallions [7, 9, 10].

Brucellosis is associated with tremendous economic loses and enormous public health problems. The economic importance of equine brucellosis is based on infertility problems and decrease productivity or performance associated with the disease in most stables and recreational centers [5]; costs of treatment and biosecurity or control programs against the disease, financial losses due to emergency slaughter of infected animals and trade restrictions in animals or their products [11]. Studies on the impact of brucellosis on econometrics of livestock production in Nigeria are few and dated but the most recent report in 1996 estimated an annual loss of US$3.2 million in only two States in the country [12].

The public health importance of brucellosis lies in very low infective dose of B. melitensis and B. abortus, estimated at 10 - 100 colony-forming units [13] and ease of transmission of Brucella agents from animals to humans via multiple routes, especially consumption of raw or undercooked animal products (meat and milk) from infected animals [14]. Control of human infection with zoonotic food borne pathogens such as Brucella is a daunting task because food habits are very difficult to change. Horses are slaughtered for human consumption and the meat sometime preferred over other meat types in parts of Enugu State. Slaughterhouse workers and others in the livestock industry are occupationally at risk of Brucella infection but strict adherence to workplace safety measures, such as use of protective wears (PWs) during routine duties, may greatly reduce the odds of the infection.

In most developed countries, brucellosis has been effectively controlled but the disease continues to devastate most parts of tropical Africa and Asia; where livestock production is incidentally a major means of livelihood [3, 6]. Establishment of appropriate control measures against brucellosis in a population depends on estimation of the disease burden in the population [15]. Serological test such as Rose Bengal Plate Test (RBPT) has been recommended for epidemiological screening for brucellosis because the test is sensitive, economical and easy to perform [16]; especially in resource limited parts of the world, where other methods of brucellosis diagnosis are rarely undertaken, due to cost, skills and laboratory infrastructural issues [3].

There is no published data on equine brucellosis in Enugu State despite the endemicity of the disease in Nigeria [4]; and large scale multipurpose use of horses in the study area. Additionally, there is dearth of information on the role of horse carcass processors on practices that facilitate dissemination of Brucella infections during routine slaughterhouse operations. The importance of horses in the epidemiology of transmission of Brucella infection, due to its close association with ruminants (considered reservoir of Brucella infection to horses) and human, may be significant and therefore needs to be investigated. Consequently, the study was conducted to determining the seroepidemiology of equine brucellosis and role of horse carcass processors in spread of Brucella infection in Enugu State, Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection

Research visits to various horse slaughter points in Enugu State for blood sample collection, were made once weekly for six months; covering three months of dry season (December to February) and another three months of rainy season (June to August). Simple random sampling method was used to select horses to be sampled. The sex of each selected animal was determined by visual examination. The age was estimated as described by Richardson et al. [17] and then categorized as young (1- 5 years), adult (6-12 years) and old (> 12 years). Foals (< 1 year) were not presented for slaughtered and therefore not included in the study. About five milliliter of blood was aseptically collected into a 15mL test tube from the severed jugular vein of each selected animal immediately after bleeding. The blood samples were allowed to clot and then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 minutes. Sera samples formed were decanted into a clean labeled sample bottle and stored at -20ºC for serological screening.

Sample screening

The RBPT was performed by mixing equal volumes (30 µL) of stained Brucella antigen and serum samples as described by Alton et al. [18] . The RBPT reagents were sourced from the Veterinary laboratory agency, United Kingdom and preserved at -20ºC. Sera samples that formed distinct granules (agglutination) within four minutes of stirring the serum-antigen mixture were recorded as positive, containing detectable amounts of Brucella antibodies, while absence of agglutination was recorded as negative.

Questionnaire survey

Structured questionnaires were used to extract information on: educational level, awareness on brucellosis, use of PWs during slaughter operations and method of disposal of eviscerated fetuses or pregnant uterine content; from 94 randomly selected horse carcass processors who consented to participate in the study. The questionnaire survey was conducted in the form of interview, in native language, to respondents who were limited in their ability to read or write. Thereafter, completed copies of the questionnaire were retrieved, the responses collated and statistically analyzed.

Data analysis

Chi-square statistics was used to test for association (P<0.05) between Brucella seropositivity and age, sex, and season. The statistics was also used to test for association (P<0.05) between educational levels of the respondents and awareness of brucellosis and involvement in practices that aid spread of Brucella infection. The tests were performed using IBM® SPSS (Statistical Package for Scientific solutions) version 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois) at 5% probability level.

RESULTS

Seroprevalence of Brucella antibodies

The study recorded an overall seroprevalence of 3% (12/402). Results on the seroprevalence of Brucella antibodies according to age, sex and season in the 402 horses screened are presented in Tables 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Old (> 12 years) horses had the least seroprevalence of 1.9% while young (1-5 years) horses had the highest seroprevalence of 8.8%. Seroprevalence of 6.8% and 1.4% were recorded in mares and stallions respectively. Significant associations (p<0.05) was found between Brucella seropositivity and age and sex while there was no association found at p = 0.294) between occurrence of Brucella antibodies and seasons.

Socioeconomic status, awareness of brucellosis and slaughterhouse practices of respondents

Information on the socioeconomic status, awareness of brucellosis and slaughterhouse practices of horse carcass processors surveyed is presented in Table 4. Majority (64.9%) of the respondents have not heard of brucellosis. Slaughterhouse practices aiding spread of Brucella infection and the percentage of horse carcass processors involved were: non-use of PWs during slaughterhouse operations (77.7%), sale of eviscerated fetuses or pregnant uterine contents for human consumption (38.3%) and discard of fetuses or pregnant uterine tissues by open dump method of waste disposal (68.1%). There were significant association (p<0.05) between educational levels of the respondents and awareness of brucellosis and sale of fetuses for human consumption (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

The 3% seroprevalence of Brucella antibodies recorded in this work is lower than 14.7% and 16% reported respectively by Ehizibolo et al. [2] and Ardo et al. [9] in other parts of Nigeria. Despite the low seroprevalence, evidence of Brucella infection in a multipurpose animal like horse should be taken seriously; considering the excruciating economic and public health consequences associated with brucellosis in both human and animal populations. The economic importance of equine brucellosis is based on infertility and decrease performance problems caused by the disease. Brucella agents display tropism to gravid uterus, where it invade developing fetuses and associated maternal tissues, resulting in middle or late term abortion, pathognomonic of brucellosis in pregnant animals [19]. Other economically important clinical manifestations of brucellosis in mares include repeat breeder syndrome, increased foaling interval, mastitis, decreased milk yield and birth of weak or unthrifty foals [9]. Pain and discomfort associated with “poll-evil” in Brucella infected horses greatly reduces performance of the animals used for sports or security purposes. Additionally, the lesion of “pull evil” is an offence to the aesthetic sensibility of tourists and holiday makers, who may not want to ride infected horses in recreational centers. The resultant effect of all these is economic losses due to brucellosis.

Apart from the economic losses, the public health and food safety implications of equine brucellosis may be significant considering: the fact that horses enjoy very close contact with human beings, multipurpose use of the animals in modern human society; including its use for shepherding ruminants (considered reservoirs of Brucella infection to horses) and as food animal in parts of Nigeria. This makes horse very significant in the epidemiology of Brucella infections from animals to humans and vice versa, particularly via inhalation in overcrowded areas cohabited by humans and animals. Humans may also acquire Brucella infection from animals following consumption of infected raw or undercooked animal product (milk and meat) and through direct or indirect contact with fluid or tissues from infected animals.

The predominance of Brucella antibodies in mares is not surprising because Brucella organisms have predilection for the female reproductive tract, pregnant uterus or fetal tissues; because of the production of erythritol, a 4-carbon sugar in the organs which facilitates the proliferation and growth of the organisms [19]. Additionally, mares are generally kept for longer period in stables than the stallion and this extended period of stay tend to predispose them to Brucella infection. Furthermore, stress associated with pregnancy and lactation reduces immunity of the mares and puts them at greater risk of being infected by disease agents such as Brucella.

Similarly, the preponderance of Brucella antibodies in young horses aged 1-5 years, may be attributed to exaggerated sexual activities of the young animals shortly after attainment of sexual maturity. Fillies usually become sexually matured at 12 to 15 months of age, even though puberty may be attained earlier at 9 to 10 months or very lately at 18 months [20]. On the other hand, semen production begins in most stallions as early as 12 to 14 months of life but successful breeding usually starts at 15 months of age or latter [20]. The significance of old horses (aged 12 years and above) in spread of Brucella infection, especially those infected shortly after sexual maturation, is that they develop chronic carrier status characterized by low circulating antibodies levels [3, 21]. The antibody level may be too low to be detected during serology but the carrier mares shed large amounts of the Brucella agent into the environment. Recently, Brucella spp was detected in milk from seronegative in Algeria [21]. The infected aged animals remain ready-source of the infection, particularly to young stallions, for onward transmission to other animals, especially females on heat.

Furthermore, the aged horses are usually culled due to infertility or poor performance problems and may be slaughtered for human consumption in places where horse meat is consumed. When slaughtered, such animals, despite their low antibody levels, remain potent source of Brucella infection to humans, especially when workplace safety measures are ignored during slaughterhouse operations or meat processing.

Poor awareness of brucellosis, as evidenced in 64.9% of the respondents who had not heard of the disease is worrisome. This is because poor awareness of brucellosis may put individuals, who are occupationally exposed to the disease, at greater risk of the infection as they may not know or adopt appropriate preventive measures against the infection. Non-use of PWs by 77.7% of horse carcass processors surveyed shows that they are not only at risk of Brucella infection but represents an important link in the epidemiology of spread of Brucella organisms from horses to humans in the study area. An effective control to this important epidemiological link in the disease spread is provision of free PWs for compulsory use to all occupationally exposed individuals, especially slaughterhouse workers; and imposition of harsh sanctions against defaulters to limit the disease spread.

Sale of eviscerated fetuses or pregnant uterine tissues for human consumption or disposing same by open air dump method of waste disposal are easy means of spreading Brucella infection since the organism has predilection for mature female reproductive tract and fetal tissues. Open air dump method of disposal of fetuses or pregnant uterine contents favours the contamination of pasture and pasture land with Brucella species. This makes acquisition of Brucella infection inevitable for animals grazing around the disposal sites. The sale of fetuses or pregnant uterine content for human consumption equally predisposes buyers to Brucella infection, especially during handling and processing of the meat.

CONCLUSION:

The overall seroprevalence of 3% recorded in this study for Brucella antibodies in horses, shows that equine brucellosis exists in Enugu State. Age and sex were important risk factors identified for equine brucellosis. Horse carcass processors were massively involved in slaughterhouse practices that aid dissemination of Brucella infection and therefore may be playing critical roles in spread of the infection in Enugu State. Although the 3% seroprevalence recorded in this study is low; there is need for institution of holistic brucellosis control programs, using One Health approach, to minimize the untoward public health and economic consequences of equine brucellosis in the study area. Such programs should include awareness creation on the dynamics of Brucella spread in human and animal populations and mass vaccination of livestock against brucellosis. Provision of free protective clothing to horse carcass processors and other workers who are occupationally exposed to brucellosis, for compulsory use during routine duties is pertinent to limit spread of Brucella infection and safeguard human and animal health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Authors acknowledge the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. The authors are also grateful to authors / editors / publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed.

FUNDING

The authors did not receive any financial assistance for this work but solely financed the work by themselves

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest and therefore so declare.

References:

-

Ihedioha IJ, Agina O. Haematological profile of Nigerian horses in Obollo-afor, Enugu State. Journal of Veterinary and Applied Sciences 2014; 4:1-8.

-

Ehizibolo DO, Gusi AM, Ehizibolo PO, Mbuk EU, Ocholi RA. Serologic prevalence of brucellosis in horse stables in two northern states of Nigeria. Journal of Equine Science 2011; 22:17-19

-

Ducrotoy M, Bertu WJ, Matope G, Cadmus S, Conde-Álvarez R, Gusi AM et al. Brucellosis in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current challenges for management, diagnosis and control. Acta Tropica 2017; 165: 179-193.

-

Onunkwo JI, Njoga EO, Nwanta JA, Shoyinka SVO, Onyenwe IW, Eze JI. Serological survey of porcine Brucella infection in Southeast, Nigeria. Nigerian Veterinary Journal 2011; 32: 60-62.

-

Colavita G, Amadoro C, Rossi F, Fantuz F, Salimei E. Hygienic characteristics and microbiological hazard identification in horse and donkey raw milk. Veterinaria Italiana 2016; 52; 21-29.

-

Ducrotoy MJ, Bertu WJ, Ocholi RA, Gusi AM, Bryssinckx W, Welburn S et al. Brucellosis as an emerging threat in developing economies: Lessons from Nigeria. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2014; 8: e3008.

-

Ocholi RA, Bertu WJ, Kwaga JK, Ajogi I, Bale OOJ, Okpara J. Carpal bursitis associated with Brucella abortus in a horse in Nigeria. Veterinary Record 2004; 155: 566-567.

-

Nicoletti PL. Brucellosis. In: Sellon DC, Long MT (editors). Equine infectious disease. Missouri: Saunders Elsevier: 2007. p. 281-295.

-

Ardo MB, Abubakar DM. Seroprevalence of horse (Equus caballus) brucellosis on the Mambilla plateau of Taraba State, Nigeria. Journal of Equine Science 2016; 27: 1-6.

-

Tijjani AO, Junaidu AU, Salihu MD, Farouq AA, Faleke OO, Adamu SG, Musa HI, Hambali IU. Serological survey for Brucella antibodies in donkeys of north-eastern Nigeria. Tropical Animal Health and Production 2017; 49:1211-1216.

-

McDermott J, Grace D, Zinsstag J. Economics of brucellosis impact and control in low-income countries, Revue scientifique et technique (International Office of Epizootics) 2013; 32: 249-261.

-

Brisibe F, Nawathe DR. Bot CJ. Sheep and goat brucellosis in Borno and Yobe States of arid Northeastearn Nigeria. Small Ruminant Research 1996; 20: 83-88.

-

Pappas G, Panagopoulou P, Christou L, Akritidis N. Brucella as a biological weapon. Cellular and Molecular Life Science 2006; 63: 2229 -2236.

-

Dean AS, Crump L, Greter H, Schelling E, Zinsstag J. Global burden of human brucellosis: a systematic review of disease frequency. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2012; 6:e1865.

-

Kaltungo BY, Saidu SNA, Sackey AKB, Kazeem HM. A review on diagnostic techniques for brucellosis. African Journal of Biotechnology 2014; 13: 1-10.

-

Diaz R, Casanova A, Ariza J, Moriyon I. The Rose Bengal test in human brucellosis: a neglected test for the diagnosis of a neglected disease. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2011; 5:e950.

-

Richardson JD, Cripps PJ, Hillyer MH, O'Brien JK, Pinsent PJ, Lane JG. An evaluation of the accuracy of ageing horses by their dentition: a matter of experience? Veterinary Record 1995; 137: 88-90.

-

Alton GG, Jones IM, Angus RD, Verger JM. Techniques for brucellosis laboratory. Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (National Institute of Agricultural Research), 1998; Paris France.

-

Petersen E, Rajashekara G, Sanakkayala N, Eskra L, Harms J, Splitter G. Erythritol triggers expression of virulence traits in Brucella melitensis. Microbes and Infection 2013; 15: 440-449

-

Anonymous, Equine reproductive maturity in mares and stallions. Available at http://equimed.com/health-centers/reproductive-care. Accessed online on March 10, 2018.

-

Sabrina R, Taha MH, Bakir M, Asma M, Khaoula B. Detection of Brucella spp. in milk from seronegative cows by real-time polymerase chain reaction in the region of Batna, Algeria, Vet. World, 2018; 11: 363-367.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License