IJCRR - 4(15), August, 2012

Pages: 165-170

Date of Publication: 15-Aug-2012

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

HERPES ZOSTER OF TRIGEMINAL NERVE: A CASE REPORT AND REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Author: Sandeepa N. C., Manoj Kumar A D, Umesh Malavalli Devraju, Syed Shahbaz, Vijay Guduba

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Herpes zoster (HZ), commonly called shingles taken from the Latin word cingulum, meaning belt, is an acute skin infection associated with the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (the virus that causes primary infection chickenpox). The risk of HZ increases with age; approximately half of all cases occur in persons older than 60 years. One of the most common and debilitating sequelae of HZ is postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), defined as pain persisting more than 3 months after the rash has healed. During chicken pox infection, the virus enters the cutaneous nerves and then travels to the dorsal root ganglia where it lies dormant until something triggers it to become active again. Stress, illness, dental manipulation, emotional upset, immuno-suppressant drugs, fatigue and radiation therapy can trigger the latent virus to travel back down the sensory nerve to infect the surface of the skin. The practising dentist must be familiar with the presenting signs and symptoms of patients experiencing the prodromal manifestations of herpes zoster of the trigeminal nerve. A thorough knowledge of the disease will prevent unnecessary and delayed treatment. Here we report a case of herpes zoster which presented with difficulty in opening mouth and intraoral pustules which was diagnosed at the earliest and was given the proper treatment.

Keywords: Herpes zoster (HZ), Shingles, Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN)

Full Text:

CLINICAL FEATURES

The clinical feature of HZ can be grouped into 3 phases.1) prodrome, 2) acute, 3) chronic. During initial viral replication, active ganglionitis develops with resultant neuronal necrosis and severe neuralgia. This inflammatory reaction is responsible for the prodromal symptoms of intense pain that preceeds the rash in more than 90%of cases. Prodromal symptoms that herald HZ include pruritus, dysesthesia, and pain along the distribution of the involved dermatome and may be mistaken for myocardial infarction, biliary or renal colic, pleurisy, dental pain, glaucoma, duodenal ulcer, or appendicitis, leading to misdiagnosis and potentially mistreatment. In rare instances, the nerve pain is not accompanied by a skin eruption, a condition known as zoster sine herpete1 . The classic skin findings are grouped vesicles on a red base in a unilateral, dermatomal distribution. However, the lesions of HZ progress through stages, beginning as red macules and papules that, in the course of 7 to 10 days, evolve into vesicles and form pustules and crusts. The exanthema typically resolves in within 2-3 weeks in otherwise healthy individuals Typically, HZ is unilateral, does not cross the midline, and is localized to a single dermatome of a single sensory ganglion (adjacent dermatomes are involved in 20% of cases). The most common sites are the thoracic nerves and the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus, which occurs in 10% to 20% of HZ episodes, can involve the entire eye, causing keratitis, scarring, and vision loss. An early sign of this condition is vesicles on the tip, side, or root of the nose (Hutchinson sign). Herpes zoster of the second and third divisions of the trigeminal nerve may produce symptoms and lesions in the mouth, ears, pharynx, or larynx. Ramsay hunt syndrome, ie, facial paralysis and lesions of the ear (zoster oticus) that are often accompanied by tinnitus, vertigo, and deafness, results from involvement of the facial and auditory nerves. Some cases of Bell palsy may be a form of zoster sine herpete. Disseminated HZ occurs primarily in immunocompromised patients; it usually presents with a dermatomal eruption followed by dissemination. Oral lesions occur with trigeminal nerve involvement andmay be present on the movable or bound mucosa. The lesions often extend to the midline andfrequently are present in conjunction with involvement of the skin overlying the affected quadrant. Individual lesions manifest as 1-4mm white opaque vesicles that rupture to form shallow ulcerations. Differential diagnosis includes herpes simplex virus infection, impetigo, contact dermatitis, insect bites, autoimmune blistering disease, dermatitis herpetiformis, and drug eruptions Several reports have documented significant bone necrosis with loss of teeth in areas involved with HZ because of close anatomical relationship between nerves and blood vessels within neurovascular bundles, inflammatory process within nerves have the potential to extend to adjacent blood vessels2 . The average interval between the appearance of the exanthema and the osteonecrosis is 21 days but has been reported as late as 42 days. The neurologic complications of HZ may include acute or chronic encephalitis, myelitis, aseptic meningitis, retinitis, autonomic dysfunction, motor neuropathies, Guillain-Barré syndrome, hemiparesis, and cranial or peripheral nerve palsies3 . More common complications include bacterial super infection by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes, scarring, and hyperpigmentation. Diagnosis Herpes zoster is usually diagnosed clinically by the prodromal pain, characteristic rash, and distinctive distribution but other procedures may be necessary in atypical cases. Although shell vial viral culture remains the criterion standard test, detection of viral DNA by polymerase chain reaction, is the most useful test because it is sensitive and specific and results can be obtained within a few hours. Other tests are direct fluorescent antibody staining, immunoperoxidase staining, histopathology, and Tzanck smear4 . TREATMENT OF ACUTE HZ: The goal of treatment during the acute episode is to control symptoms and prevent complications. Treatment options include antiviral therapy, corticosteroids, and pain medication5 Antivirals Acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir are nucleoside analogues that inhibit replication of human herpes viruses. These agents reduce the duration of viral shedding, hasten rash healing, reduce the severity and duration of acute pain, and reduce the risk of progression to PHN. These medications are most effective if initiated within 72 hours after the development of the first vesicle. Valacyclovir and famciclovir may be more successful than acyclovir in reducing the prevalence of post herpetic neuralgia. Immunocompromised patients are at greater risk of complications and may require intravenous antiviral therapy. Analgesics Acute pain will be reduced by antiviral drugs, but patients will generally also require analgesics. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are usually ineffective, and opioids may be required. Corticosteroids Review of the data indicated a reduction of pain and disability during the first 2 weeks but no effect on the incidence or severity of post-herpetic neuralgia. In combination with antiviral therapy, they modestly reduce the severity and duration of acute symptoms. Corticosteroids are associated with a considerable number of adverse effects and hence should be used only in patients with severe symptoms at presentation or in whom no major contraindications to corticosteroids exist Postherpetic Neuralgia (PHN) and Management Approximately 15% of affected patients progress to the chronic phase of HZ, which is charecterised by pain (PHN) that persists longer than 3 months after the initial presentation of acute rash. PHN Greater than 25% of patients with HZ will experience PHN over 1 yr. The V-Z virus injures the peripheral nerves by demyelination, wallerian degeneration and sclerosis but change in CNS, including atrophy of dorsal horn cells in the spinal cord, have also been associated with PHN. This combination of central andperipheral injury results in the spontaneous discharge of neurons and an exaggerated response to non painful stimuli. There is also evidence to support the theory that a low grade persistent infection of the ganglion contributes to the PHN pain. Effective therapy often requires multiple drugs. Another general principle is to have patients begin a medication at a very low dose and increase the dose gradually until either analgesia or adverse effects are noticed. It is usually best to begin with a medication that either has the fewest adverse effects or that is perhaps associated with desirable side effects. For example, topical medications are almost always free of systemic adverse effects. Conversely, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) often have sedating side effects that may be helpful for patients who suffer from insomnia. Medications that are in use include the following: topical agents, opioids, antidepressants and anticonvulsants5 . Topical Agents Topical lidocaine patches are particularly effective for patients with allodynia. Lidocaine works by decreasing small fiber nociceptive activity, and the patch itself serves as a protective barrier 6 . Capsaicin is another topical agent that has shown efficacy in randomized clinical trials. However, the burning sensation associated with the application of capsaicin often limits its clinical use7 .However, the medication‘s effect often does not occur until 2 weeks or more of therapy. Capsaicin is derived from red peppers andis not recommended for placement on mucosa or open cutaneous lesions. Opioids Their long-term use presents with risks of sedation, mental clouding, and abuse. Because elderly people bear the overwhelming burden of PHN and also have comorbidities that may limit the use of other medications, opioids may have a role in the treatment of these patients. Mixed μ- opioid agonists and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors such as tramadol may be good choices for patients with PHN, especially for those with risk factors for substance abuse. Other reasonable options include oxycodone with acetaminophen, or morphine. When prescribing opioids, clinicians should recommend prophylactic constipation therapy from the outset in the form of a stool softener and laxative Antidepressants Tricyclic antidepressants are the criterion standard for relieving the pain of PHN. Multiple clinical studies have shown the efficacy of nortriptyline and amitriptyline, the most commonly used members of this class8 . Unfortunately, TCAs are often associated with a variety of anticholinergic adverse effects, sedation, and potential cardiac dysrhythmias. Patients who are unable to tolerate TCAs may do better with selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, such as duloxetine or venlafaxine. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants effectively relieve depression symptoms but they do not specifically relieve neuropathic pain. Anticonvulsants Several anticonvulsants are of use against neuropathic pain. The newer-generation anticonvulsant drugs, such as pregabalin and gabapentin, have fewer adverse effects and require less hematologic monitoring than older anticonvulsants, such as carbamazepine and valproic acid. Pregabalin and gabapentin have both been shown to relieve the pain of PHN9 .Pregabalin has the advantage of a more predictable and linear pharmacokinetic profile. Other therapeutic modalities that have been proposed for PHN include electrical stimulation of the thalamus, anterolateral cordotomy, cryotherapy of the intercostal nerves, and ablation of the dorsal roots using pulsed radiofrequency; however, limited data exist to support these therapies.

PREVENTION

Zostavax is a live, attenuated vaccine that contains the same strain of virus as the varicella vaccines but 14 times more potent than Varivax, the vaccine for chickenpox. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving around 38,000 healthy adults older than 60 years, the vaccine reduced the incidence of HZ by 51%, the burden of illness from HZ by 61%, and the risk of PHN by 66%10.The adverse effects of the vaccine are mild and usually consist of erythema, pain, and pruritus at the injection site. Systemic adverse effects are rare and consist of fever and headache

CASE REPORT:

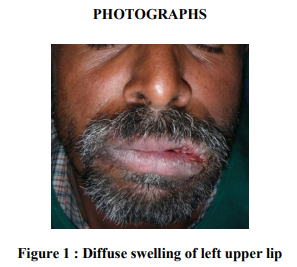

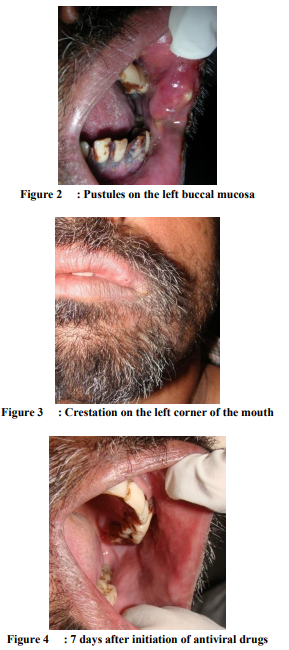

A 45 yr old male patient reported to us with a chief complaint of pain and swelling in relation to left upper lip and cheek region of duration of 2 days. Patient gave a history of eruptions on left upper lip 2 days back, which got ruptured within a day, followed which he noticed swelling of left upper lip and face and difficulty in opening mouth. Fever and body ache was noted prior to the swelling. Pain was severe, pricking type and was present on the upper lip region on the left side. There was no history of prodromal pain or burning sensation. Patient had itching sensation on the affected area .There was a previous history of chickenpox on general physical examination, there was no abnormality detected. Extra orally gross facial asymmetry on left side was noted .There was diffuse swelling on the left middle third of the face. Crestation was noted on the left middle third of the face. Upper lip along with labial mucosa and buccal mucosa was swollen on left side. Swelling was soft to firm in consistency and severely tender on palpation. There were multiple pustules noted on the left mucosa and lip which was severely tender. All the findings were lead to the tentative diagnosis of Herpes zoster of maxillary division of trigeminal nerve which was confirmed by pathological examination. He was treated with antiviral agents and corticosteroid. There was improvement in his general condition and the lesion. Following 7 days of antiviral therapy patient showed complete resolution of his symptoms. There was no history of pain persisted after the lesion is healed.

CONCLUSION

HZ in the orofacial region can have variable presentation. It is very important to diagnose HZ at the earliest to prevent unnecessary dental treatments and to reduce the risk of PHN.

References:

1. Barrett AP, Katelaris CH, Morris JGL :Zoster sine herpete of the trigeminal nerve ,Oral surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1993:75:173-175

2. Mendieta C, Miranda J,Brunet LI etal: alveolar bone necrosis andtooth exfoliation following herpes zoster infection: review of literature andcase report. J Periodontol 2005:76:148-153

3. Gilden DH, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, LaGuardia JJ, Mahalingam R, Cohrs RJ. Neurologic complications of the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus N Engl J Med. 2000;342(9):635-645

4. Espy MJ, Teo R, Ross TK, et al. Diagnosis of varicella-zoster virus infections in the clinical laboratory by Light Cycler PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(9):3187-3189

5. Priya S, Lisa AD, David PM. , Herpes zosterand post herpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc, 2009 March; 84(3): 274–280.

6. Rowbotham MC, Davies PS, Verkempinck C, Galer BS. Lidocaine patch: double-blind controlled study of a new treatment method for post-herpetic neuralgia. Pain 1996; 65(1):39-44

7. Watson CP, Tyler KL, Bickers DR, Millikan LE, Smith S, Coleman E. A randomized vehicle-controlled trial of topical capsaicin in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. Clin Ther. 1993;15(3):510-526

8. Wu CL, Raja SN. An update on the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. J Pain 2008;9:S19- S30

9. Rowbotham M, Harden N, Stacey B, Bernstein P, Magnus-Miller L. Gabapentin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280(21):1837-1842

10. Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. Shingles Prevention Study Group A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(22):2271-2284

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License