IJCRR - 4(14), July, 2012

Pages: 103-107

Date of Publication: 31-Jul-2012

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

A CLINICAL ANALYSIS OF EMERGENCY PERIPARTUM HYSTERECTOMY

Author: G.Ganitha

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Objectives: To determine the incidence, maternal factors, indications, associated mortality and morbidity and prophylactic measures for peripartum hysterectomy. Methods: A retrospective analysis of 18 cases of peripartum hysterectomy performed over a period of 18 months was done. Results: During the studyperiod, there were 16,385 deliveries which included 1903 cesarean deliveries. 18 cases underwent peripartum hysterectomy giving an incidence of 0.11%. The incidence following vaginal delivery was 0.12% and that of cesarean hysterectomy was 0.9%. 50% of the cases had a scar on the uterus due to previous LSCS or repair of rupture. Indication for surgery was rupture of uterus in 66.6% cases and uncontrolled PPH due to uterine atonicity in33.3% cases. All cases underwent subtotal hysterectomy. The commonest postoperative complications were hypovolemic shock (83%) and febrile morbidity (16%). Perinatal mortality was 72%. Maternal mortality was 22%. In spite of the associated intraoperative and postoperative complications, peripartum hysterectomy is still one of the important life saving procedures.

Keywords: Obstetric hysterectomy; Cesarean hysterectomy; Rupture uterus; uterine atonicity

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

Peripartum hysterectomy is hysterectomy performed at the time of delivery or during immediate postpartum period. Peripartum hysterectomy is generally performed in the setting of life threatening hemorrhage. It is a double edged sword. Though, it is a life saving procedure, it is associated with loss of reproductive ability, serious morbidity and sometimes mortality. Proper timing and meticulous care are must to reduce complications. . Several studies report incidence rates for peripartum hysterectomy ranging from 0.04% to 0.32%1-9 . The incidence and indications for peripartum hysterectomy varies with the clinical setting, patient characteristics, availability of blood banking facilities and individual practitioner skills. The present study was conducted in a tertiary care, teaching hospital catering mainly to rural population of India.

METHODOLOGY

Among the 16,385 cases admitted for delivery during the study period of 18 months, 18 cases underwent peripartum hysterectomy. These cases were analyzed by a descriptive retrospective study. Data was obtained by reviewing the obstetric admission records, operation records and intensive care unit records.

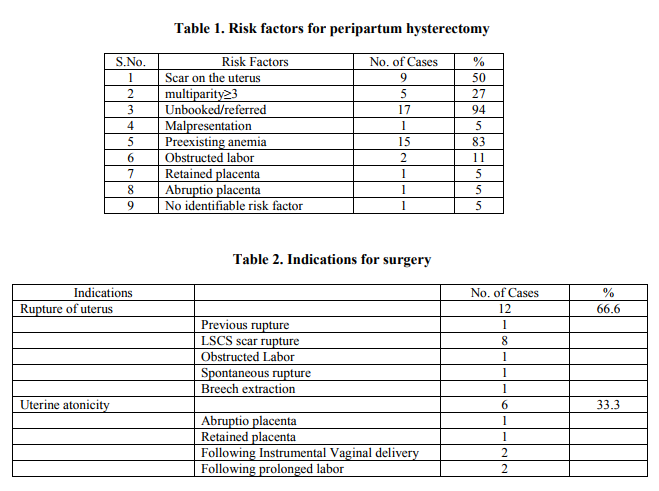

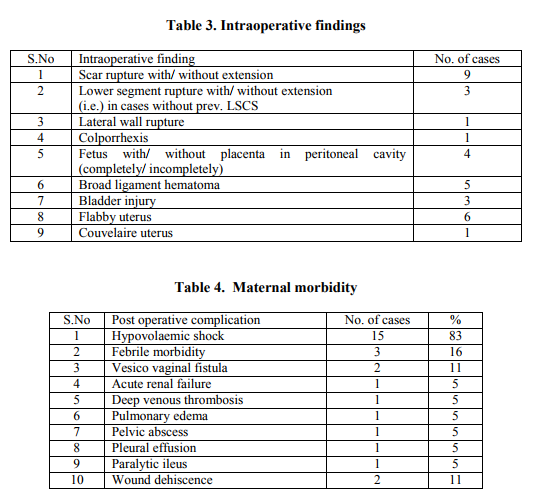

RESULTS Incidence: During the study period, there were 16,385 deliveries, out of which 1903 were cesarean deliveries. 18 cases underwent peripartum hysterectomy. Accordingly, the incidence of peripartum hysterectomy was 0.11%.The incidence of peripartum hysterectomy following vaginal delivery was 0.12% and following cesarean delivery was 0.94%. Maternal factors: Most women in the study were in the age group of 21-30years (61.1%). 5 were teenaged (27%) and 2 were above 30 years. 55% were of parity 2. There were 3 primigravidas (16%). 30% were of parity ≥3. 44% cases were referred and 50% cases were unbooked. Only one case was booked. In relation to previous pregnancy, 8 cases had undergone LSCS and 1 case had undergone repair for rupture uterus. Out of the 18 cases studied, 9 cases delivered vaginally including 2 VBAC and 2 instrumental deliveries. Labor was accelerated with ARM or oxytocin or both in 3 cases while 6 cases delivered vaginally without acceleration As shown in Table 1, the most common risk factor was scar on the uterus. The indications for surgery are enumerated in Table 2. Rupture uterus (66.6%) was the commonest indication followed by uterine atonicity (33.3%). Rupture uterus was commonest following trial of labor in previous LSCS (6 cases). Nature of surgery: All cases underwent subtotal hysterectomy. 2 cases (11%) required bladder repair. 2 cases (11%) required salpingooopherectomy. In 1 case, breech extraction was attempted and ended in uterine rupture. Decapitation followed by subtotal hysterectomy was done for the same. All patients were given general anaesthesia. No case developed anaesthetic complications or required relaparotomy. Intraperitoneal drain was kept in all cases. The intraoperative findings are summarized in Table 3. Maternal outcome: Hypovolaemic shock was seen in 15 cases. 3 cases (16%) developed febrile morbidity. Table 4 summarizes the post operative complications. At least, 2 units of blood was transfused in all cases. One patient required up to 7 units of blood transfusion. The average duration of stay in hospital was 10-15 days. Maximum duration of stay was 40 days. Maternal and perinatal mortality: There were 4 maternal deaths in the present study. The cause of death was irreversible hypovolaemic (hemorrhagic) shock. The commonest cause for hemorrhage leading to death was atonic PPH (3 cases). Perinatal mortality was 72% (13 cases) DISCUSSION Peripartum hysterectomy still remains a life saving resort in present day obstetrics. The incidence of peripartum hysterectomy in the present study is 0.11% as compared to that of Devi et al1 0.07%, Sahu et al2 0.26%, Gupta et al3 0.26%, Glaze et al4 0.08%, Knight et al5 0.04%, Mathe et al6 0.28%, Kanwar et al7 0.32%, Archana et al8 0.07%, Mukherjee et al 9 0.15%. In the present study 94% of the cases were unbooked or referred from elsewhere. Unbooked and referred cases were found to be at high risk for peripartum hysterectomy in other studies also7-9 . In the present study, 50% of the cases had scar on the uterus. 8 cases had previous LSCS and one case had undergone repair for rupture uterus. Cesarean history is associated with higher incidence of abnormal placentation and uterine rupture in the present pregnancy resulting in increased incidence of peripartum hysterectomy11. The high risk of peripartum hysterectomy associated with prior cesarean delivery has been reported in other studies as well4, 5, 10 .

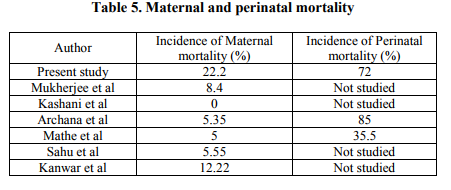

Rupture uterus was the commonest indication for peripartum hysterectomy in the present study (66.6%) followed by uterine atony (33.3%). Similarly, rupture uterus was reported as the commonest indication by Gupta et al3 70%, Archana et al8 75%, Mukherjee et al9 38.3% and Kanwar et al7 36.6%. However, uterine atony and abnormal placentation was reported as the commonest indication by Devi et al1 46%, Sahu et al2 41%, Glaze et al4 70%, Mathe et al6 40%, Kashani et al10 82%. Post operative shock and febrile morbidity were the commonest post operative complications in the present study and other studies2, 4, 7-10. The maternal and the perinatal mortality in the present study were higher than most studies. Probably, higher rate of mortality and morbidity noted were due to pre existing anemia, malnourishment, handling by untrained dais in peripheries and delayed referral. Table 5 shows the comparison of maternal and perinatal mortality in various studies. CONCLUSIONS In spite of the high incidence of intraoperative and post operative complications, peripartum hysterectomy is still one of the important life saving procedures. Though peripartum hysterectomy should be the last resort in obstetric hemorrhage, timely decision should be taken. All obstetricians should be trained to perform obstetric hysterectomies. Obstetricians should be familiarized with other management options such as the B-Lynch compression sutures and internal iliac artery ligation. Good Antenatal care, timely recognition of antepartum and intrapartum complications, timely referral of high risk cases, judicious selection of cases with prior cesarean delivery for trial of labor, careful intrapartum monitoring, active management of third stage of labor, availability of prostaglandins, good blood banking facilities and increasing familiarity of obstetricians to compression sutures and internal iliac or uterine artery ligation can reduce the incidence, morbidity and mortality of peripartum hysterectomy. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Author acknowledges the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. The author is also grateful to authors / editors / publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed.

References:

1. Praneshwari Devi R K, Singh N N, Singh D. Emergency obstetric hysterectomy. J Obstet Gynecol India 2004; 54:127-9.

2. Sahu L, Chakravertty B, Sabral P. Hysterectomy for obstetric emergencies. J Obstet Gynecol India 2004; 54:34-6.

3. Gupta S, Dave A, Bandi G et al. Obstetric hysterectomy in modern day obstetrics: a review of 175 cases over a period of 11 years. J Obstet Gynecol India 2001; 51:91- 3.

4. Sarah Glaze, Pauline Ekwalanga, Gregory Roberts et al, Peripartum Hysterectomy: 1999 to 2006 Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2008; 111: 732-738.

5. Knight M; UKOSS, Peripartum hysterectomy in the UK: management and outcomes of the associated hemorrhage. BJOG. 2007 114:1380- 7.

6. Jeff Kambale Mathe, Ahuka Ona Longombe. Obstetric hysterectomy in rural Democratic Republic of the Congo: an analysis of 40 cases at Katwa Hospital, African journal of reproductive health 2008; 12(1):60-6.

7. Kanwar M, Sood P L, Gupta K B, et al. Emergency hysterectomy in obstetrics. J Obstet Gynecol India 2003; 53 (4):350-2.

8. Kumari Archana, Sahay Priti Bala. A clinical review of emergency obstetric hysterectomy. J Obstet Gynecol India 2009; 59(5): 427-431.

9. Mukherjee P, Mukherjee G, Das C. Obstetric hysterectomy: A review of 107 cases. J Obstet Gynecol India 2002; 52:34-6.

10. Kashani E, Azarhoush R. Peripartum hysterectomy for primary postpartum haemorrhage: 10 years evaluation. European journal of experimental biology 2012;2 (1):32-6.

11. Whiteman M K, Kuklina E, Hillis S D, Jamieson D J, Meikle S F, Posner S F, Marchbanks P A. Incidence and determinants of peripartum hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108 (6):1486–92.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License