IJCRR - 4(20), October, 2012

Pages: 143-148

Date of Publication: 20-Oct-2012

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

ANOMALOUS ORIGIN OF HEPATIC ARTERY AND ITS RELEVANCE IN HEPATOBILIARY SURGERIES

Author: Sunita Sethy, G. R. Nayak, D. Agrawal, B. Mohanty, R. Biswal

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Background: Introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, hepatobiliary surgeries and liver transplantations has stimulated a renewed interest in hepatic arterial anatomy. The variant arterial anatomy recognized during routine cadaveric dissection offers great learning potential. This imparts the concept of patient individuality and subsequent individualization of medical and surgical therapies and helps the surgeons for safe surgery and low morbidity. Objective of the study: To report on hepatic artery variations observed in the dissecting room and to find out the different pattern of hepatic arteries by cadaveric dissection. Materials and Methods: Twenty five human cadavers of SCB Medical College were dissected to study the source and pattern of hepatic arterial supply to liver. Results: Twenty four cadavers exhibited typical common hepatic arterial supply from the celiac trunk. Only one female body out of twenty five cadavers had an anomalous origin of common hepatic artery. Common hepatic artery originated from the superior mesenteric artery. Conclusion: Aberrant hepatic vascularisation should be assessed preoperatively to avoid fatal complications in hepatobiliary surgeries.

Keywords: Hepatic artery, Superior mesenteric artery, Hepatobiliary surgeries.

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

In adults the Common Hepatic Artery (CHA) is intermediate in size between the left gastric and splenic arteries. In fetal and early postnatal life it is the largest branch of the coeliac axis. The hepatic artery gives off right gastric, gastroduodenal and cystic branches as well as direct branches to the bile duct from the right hepatic and sometimes the supraduodenal artery. It may be subdivided into the common hepatic artery, from the coeliac trunk to the origin of the gastroduodenal artery, and the hepatic artery ‘proper', from that point to its bifurcation. It passes anterior to the portal vein and ascends anterior to the epiploic foramen between the layers of the lesser omentum. Within the free border of the lesser omentum the hepatic artery is medial to the common bile duct and anterior to the portal vein. At the porta hepatis it is divided into right and left branches before these run into the parenchyma of the liver. A replaced hepatic artery is a vessel that does not originate from an orthodox position and provides the sole supply to that lobe. Rarely a replaced common hepatic artery arises from the superior mesenteric artery and is identified at surgery by a relatively superficial portal vein (reflecting the absence of a common hepatic artery that would normally cross in front of the vein). More commonly a replaced right hepatic artery or an accessory right hepatic artery arises from the superior mesenteric artery. In this case they run behind the portal vein and bile duct in the lesser omentum and can be identified at surgery by pulsation behind the portal vein. The presence of replaced arteries can be lifesaving in patients with bile duct cancer: because they are away from the bile duct and hence not affected by cancer, making excision of the tumour feasible. Knowledge of these variations is also important in planning the whole and split liver transplantation. (Grays Anatomy-40th edition, Liver, 1169-70). The hepatic arteries may arise from the abdominal aorta, the left gastric or the superior mesenteric arteries (2). The hepatic arterial anatomy is aberrant in almost 33-41% individuals (1, 2, 3, 4). The most common anomalies include, the right hepatic artery arising from superior mesenteric artery (25%) and left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery (25%) (4) . Anomalies of the common hepatic artery, usually a branch of the celiac trunk, are relatively uncommon (5). However, Kadir et al., (1991) demonstrated angiographically a 5% incidence of the replaced common hepatic artery (6) whereas Woods and Traverso (1993) found the replaced common hepatic artery, branching off the superior mesenteric artery in 2.5% of the cases (7). An aberrant hepatic artery may cause a potential error in the angiographic diagnosis of traumatic liver hematoma (8). Moreover the existence of aberrant hepatic arteries emphasizes the mode of development of liver during perinatal period (9). Liver transplantation and peripancreatic surgery needs extensive, adequate and clear knowledge of varied blood supply of liver.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We carefully dissected twenty five cadavers of SCB Medical College Cuttack origin (twenty males and five females), aged between 45-65 years and randomly assigned to medical students for dissection over a period of three years. We took the task of dissection from origin to termination of all the major arteries supplying the liver. To study the variational anatomy of hepatic arterial supply, we decided to follow all the branches of celiac and superior mesenteric arteries. Especially all hepatic vessels were painstakingly dissected from origin to ultimate distribution in the substance of liver. We selected only those bodies, which were properly embalmed and having arteries in good condition. The dissection of arteries were done and then coloured and photographed. The measurement of length and external diameter of arteries were done by sliding Vernier Callipers.

RESULT

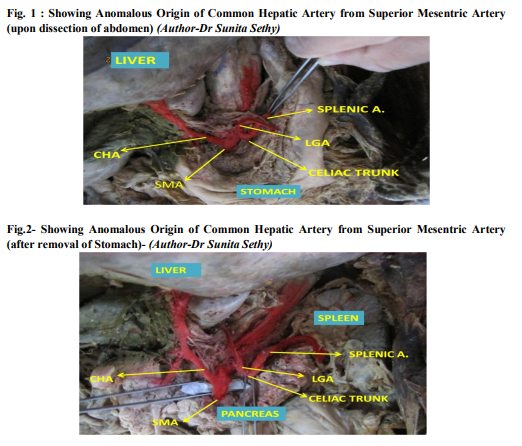

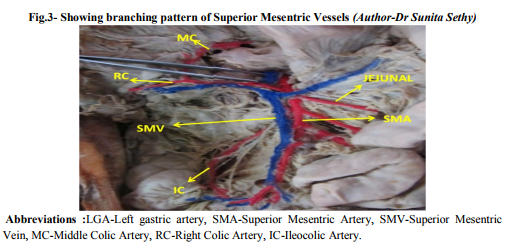

After a careful dissection of twenty five cadavers, we analyzed the variation pattern of celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery and the source and distribution of hepatic arteries. Celiac trunk: Except one, all the cadavers exhibited classical (Hepatoleinogastric) pattern of celiac trunk's origin and distribution. In a study of twenty five celiac trunks, the length of celiac trunk varied from 6 to 25mm and the width from 9 to 20 mm. The celiac trunk was constricted at its site of origin from the abdominal aorta. The distance on the aorta between the sites of origin of celiac and superior mesenteric arteries varied from 10 to 15mm. In twenty three cases, splenic artery was the largest branch of celiac trunk, whereas in two cases common hepatic was the largest branch. However left gastric was found as the first and smallest branch of celiac trunk in all cases. Anomalous celiac trunk had only 2 branches [Fig1],[Fig-2] (1)Left gastric artery (2)Splenic artery Hepatic arteries: Five cadavers exhibited three hepatic arteries, i.e., right, left and middle hepatic arteries for the right, left and quadrate lobes of the liver respectively. Twenty cadavers had two hepatic arteries, i.e., right and left. Hepatic arteries had normal celiac origin in twenty four cadavers. One common hepatic artery had a superior mesenteric origin (4%) [Fig-1and2]. The width of the anomalous common hepatic artery (16mm) was relatively wider than that of classical celiac common hepatic artery (12mm). The anomalous common hepatic artery routed to the posterior of the head of the pancreas and, entered the right margin of hepato-duodenal part of lesser omentum, where it was lying medial to the common bile duct and anterior to the portal vein. [Fig-1, Fig-2]. The CHA then gave a branchGastroduodenal artery and continued as the Proper Hepatic artery. The proper hepatic artery was further divided into 2 branches-right and left hepatic artery. The right hepatic artery further gave cystic artery. Cystic artery: In twenty cases the cystic artery was single and arising from the right hepatic artery. The left hepatic artery was found in one case and proper hepatic artery in four cases. Superior mesenteric artery: Except one, all 24 cadavers exhibited normal branching pattern. In one case the Common Hepatic Artery was the 1st branch and middle colic artery arose from the right colic artery [Fig-1, 2 and 3].

DISCUSSION

Aberrant hepatic arterial anatomy occurs in 33- 41% of reported literature (3), (6), (10). The common hepatic artery is usually a branch of the celiac trunk (2). This classical "Michels type -I" pattern with right and left hepatic arteries originating from the common hepatic artery (of celiac origin) occurs in about 55% of the population (7). Although the normal pattern of arterial supply of hepatic parenchyma and biliary tract is well described (11), there is a considerable variation in the relative contribution of normal and abnormal arteries to parenchyma and biliary tree in the presence of anomalies (12),(13). The replaced hepatic arteries (replaced right hepatic and replaced common hepatic arteries) usually do not occupy the same position in the hepatoduodenal ligament as the normally occurring hepatic artery. Those typically lie lateral to the portal vein behind the head of the pancreas and enter the lesser omentum posterolateral to the common bile duct (6), (7). In Michels 200 liver dissections, he found half of the replaced common hepatic arteries (RCHA) actually passed through the pancreatic substance while the other half passed posterior to it. In our case the common hepatic artery never entered the pancreatic tissue. It was routing to posterior of the head of pancreas and first part of the duodenum. Later it had normal course. Another classification method is the one adopted by Michel et.al in 1955 I. standard anatomy : 55 - 61 % II. replaced LHA : 3 - 10 % III. replaced RHA : 8 - 11 % IV. replaced RHA and LHA : 0.5 - 1 % V. accessory LHA from LGA : 8 - 11 % VI. accessory RHA from SMA : 1.5 - 7 % VII. accessory RHA and LHA : 1 % VIII. accessory RHA and LHA and replaced LHA or RHA : 2 - 3 % IX. CHA replaced to SMA : 2 - 4.5 % X. CHA replaced to LGA : ~ 0.5 % XI. Others o CHA separate origin from aorta : ~ 2 % o double hepatic artery§ : 3.7 % o PHA replaced to SMA; GDA origin from aorta : 0.3 % Anomalous CHA seen in our study was similar to Michels, IX type. Moreover the existence of such an arterial variant in patients having liver metastasis carries the risk of misperfusion of intraarterial chemotherapeutic agents (14). The intraarterial chemotherapy technique for isolated, nonresectable liver metastasis achieves complete perfusion of whole liver only in patients with classical arterial anatomy. Patients having variant arterial anatomy need vascular reconstruction prior to intra-arterial chemotherapy or the use of double port catheter pumps, for ideal, uniform perfusion (15). The knowledge of hepatic arterial variations can be useful in the selection of donors for partial hepatic grafts in living related liver transplantation (LRLT) (16). Such anomalies should be ruled out preoperatively (17) by angiography, Axial CT and/or DCEMRI (18). Hepatic arterial anatomy must be defined precisely to ensure optimal donor hepatectomy and graft arterialization (19). Moreover the preoperative knowledge of anomalous vessels is also helpful for modification of surgical approach (20). Arterial anomalies preserved and managed appropriately do not necessarily compromise graft outcome. To our knowledge a unique case of aberrant common hepatic artery (of superior mesenteric origin) with a anomalous celiac trunk, having only two branches-left gastric and splenic artery was found in this study. The persistence of lower half of ventral longitudinal anastomosis between the 10th to 13th splanchnic (vitelline) arterial roots that normally disappear may be the possible embryological explanation for this variability. Such variations may be attributed to the rotation of gut, caudal displacement of abdominal viscera and hemodynamic changes taking place during organogenesis and differentiation (21), (22).

CONCLUSION

In our study we found a variant of celiac trunk, replaced common hepatic artery taking origin from superior mesenteric artery in (4%) of our dissections which is not very uncommon. Vascular injuries are the most lethal technical injuries encountered in laparoscopic cholecystectomy (24). Injury to hepatic blood supply is more common in the presence of aberrant arterial anatomy. Preoperative knowledge of normal and variant arterial anatomy can prompt to take measures to preserve the vessels and avoid fatal injury (25). The aberrant vessels can be identified on visceral angiography, dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCEMRI) and/or spiral CT [18].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all the students of SCB Medical College, Cuttack, Odisha who were assigned to dissection of cadavers for their efforts in data collection and those authors and scholars mentioned in the reference for their enlightening and informative articles, journals and books that helped to draw inferences of the study. The authors are also grateful to authors/editors/publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed.

References:

1. Michels NA. Variations in blood supply of liver, gallbladder, stomach, duodenum and pancreas. Year book of the Am Philosophical soc, 1943: 150.

2. Last RJ. Vessels and nerves of the gut. In: Sinnatamby CS, editor. Last's Anatomy: Regional and Applied. 10 th Ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999: 236-238, 254- 6.

3. Kemeny MM, Hogan JM, Goldberg DA et al. Continuous hepatic artery infusion with an implantable pump: problems with hepatic artery anomalies. Surgery. 1986 Apr;99(4):501–504.

4. Rosse C, Gaddum-Rosse P. The gut and its derivatives. In: Hollinshead's textbook of Anatomy. 5` h Ed. Philadelphia: LippincottRaven, 1997: 568-80.

5. Michels NA. Newer anatomy of the liver and its variants blood supply and collateral circulation. Am J Surg 1966; 112: 337-47.

6. Kadir S, Lundell C, Saeed M. Celiac, Superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. In: Kadir S, editor. Atlas of normal and variant angiographic anatomy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1991: 297-308.

7. Woods MS and Traverso LW. Sparing a replaced common hepatic artery during pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am Surg 1993; 59: 719-21.

8. Konstam MA, Novelline RA, Athanasoulis CA. Aberrant hepatic artery: a potential cause for error in the angiographic diagnosis of traumatic liver hematoma. Gastrointest Radiol 1979; 4: 43-5.

9. Severn CB. A morphological study of the development of the human liver (II), establishment of liver parenchyma, extrahepatic ducts and associated venous channels. Am J Anat 1972; 133: 85.

10. Lygidakis NJ, Makuuchi M. Pitfalls and complications in the diagnosis and management of hepatobiliary and pancreatic disease. Thieme Med Inc, 1993: 113, 231.

11. Padbury R, Anatomy AD. In: Toouli J, editor. Surgery of the biliary tract. Edinburgh: Chuchill Livingstone, 1993: 3-19.

12. Makisalo H, Chaib E, Krokos N, Calne R. Hepatic arterial variations and liver related diseases of 100 consecutive donors. Transpl Int 1993; 6: 325-9.

13. Shaw BWJ, Wood RP, Stratta RJ et al. Management of arterial anomalies encountered in split liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 1990; 22: 420-2.

14. Civelek AC, Sitzmann JV, Chin BB et al. Misperfusion of the Liver during hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy. Am J Roentgenol 1993; 160: 865-70.

15. Eid A, Reissman P, Zamir G, Pikarsky AJ. Reconstruction of replaced right hepatic artery, to implant a single-catheter port for intra-arterial hepatic chemotherapy. Am Surg 1998; 64: 261-2.

16. Daly JM, Kemeny N, Oderman P, Botet J. Long term hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy. Arch Surg 1984; 119: 936- 41.

17. Dooly WC, Cameron JL, Pitt HA et al. Is preoperative angiography useful in patients with periampullary tumors? Ann Surg 1990; 211: 649-55.

18. Muller MF, Meyenberger C, Bertschinger P et al. Pancreatic tumors: Evaluation with endoscopic US, CT and MR imaging. Radiol Soc N Am 1994; 190: 745-51.

19. Takayama T, Makuuchi M, Kawarasaki H, et al. Hepatic transplantation using living donors with aberrant hepatic artery. J Am Coll Surg 1997; 184: 525-8.

20. Volpe CM, Peterson S, Hoover EL, Doerr RJ. Justification for visceral angiography prior to pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am Surg 1988; 64: 758-61

21. Reuter ST, Redman HC. Vascular anatomy. In: Gastrointestinal angiography, 2nd Ed. Philadelphia, London, Toronto: W B Saunders, 1977: 31-65.

22. Arey LB. Developmental Anatomy: A textbook and laboratory manual of embryology. 7 th Ed. Philadelphia: W B Saunders, 1974.

23. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice by S Standring, Elsevier Health Sciences, 40th edition, 1169-70.

24. Deziel DJ, Millikan KW, Economou SG, Doolas A, Ko ST, Airan MC. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A national survey of 4292 hospitals and an analysis of 77604 cases. Am J Surg 1993; 165: 9-14.

25. Biehl TR, Traverso LW, Hauptmann E, Ryan JA Jr. Preoperative visceral angiography alters intraoperative strategy during the whipple procedure. Am J Surg 1993; 165: 607- 12.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License