IJCRR - 4(20), October, 2012

Pages: 15-25

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

AN ASSESSMENT OF TRAINING AND SALESFORCE PRODUCTIVITY IN THE NIGERIA'S MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY: LESSON FROM NASCO COMPANY LTD, JOS

Author: Meshach Gomam Goyit, Dakung Reuel Johnmark

Category: General Sciences

Abstract:Training is very important and so viable that organizations cannot do without it. If organizations want to succeed and even achieve goals and objectives, reliance on the skills and knowledge of their sales force to deliver products and services to the market place becomes imperative. Deploying and sustaining a highly skilled and competitive sales force requires a strong management commitment towards effective initial and on-going training solutions. A remote training program is capable of delivering a continuous curriculum of training solutions to meet the needs of both new and veteran members of the deployed sales force. The problem under focus was to assess the impact of training on sales force productivity in the Nigeria's manufacturing industry, using Nasco company Ltd, Jos as a case study. The data obtained from secondary sources were analyzed and the hypothesis formulated was tested using regression analysis. The result from the hypothesis tested revealed that there is a significant relationship between investment in training and profit of Nasco Company Ltd. Based on our findings we recommended that: rather than outsourcing the distribution of its products, Nasco Company should train its sales force personnel. Since investment in training of the sales force enhances the company's productivity as well as company's profit, the company under review should invest more on the training of its sales force.

Keywords: Training, Sales force, Productivity

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

The basis for the development of any country depends on the level of training. Training is very important and so viable that organizations cannot do without, if an organization wants to succeed and even achieve its goals and objectives. Companies rely on the skills and knowledge of their sales force to deliver products and services to the market place. Deploying and sustaining a highly skilled competitive sales force requires a strong management commitment towards effective initial and on-going training solutions (Hall, 2005). Sales management is ultimately responsible for the direction and content of the training provided to the remote sales force, by directly or indirectly managing the training needs. A remote training program is capable of delivering a continuous curriculum of training solutions to meet the needs of both new and veteran members of the deployed sales force. According to Lorge and Smith (1998), by providing product knowledge and sales skill training to the sales force, companies can position their products into the market place, knowing that the remote sales force has the necessary skills and information to make the sale, service their customers, and recognize additional sales opportunities. The role that effective sales training plays in a firm's strategic advantage extends from home country to global business environments (Honeycutt, Ford and Simintiras, 2005). As a result, global powerhouses like Canon, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, and Saab invest sales training dollars across national borders (Hall, 2005). In 2000, $56.8 billion (N8, 520 billion) were invested in training (Galvin, 2001) of which one-quarter or $14.2 billion were devoted to sales training (Wilson, Strutton and Farris, 2002). Global firms believe that investing in sales training programs contribute positively to sales force motivation (Liu, 1996), effectiveness (Piercy, Craven and Morgan, 1998), and performance (Pelham, 2002). On average, each member of the sales force generated approximately $15,000 (N225, 000) to $25,000 (N375, 000) of revenue per day, depending upon the territory. Therefore, the time dedicated to the training needed to be both practical and effective, off-setting the missed selling opportunities when the sales representative is out of their territory. Additionally, the sales training department’s curriculum had to be flexible enough to integrate new product training to warrant the travel and lodging costs associated with the training (Skiera and Albers, 1998). According to Piercy et al. (1998), the need for training is very necessary for employee as well as organizational productivity. Training represents the single largest investment in enhancing employee productivity. Manufacturing industries in Nigeria are always emphasizing training of sales force and most often, substantial funds are being invested in it. In order to inculcate quality delivery (to satisfy customers), training and workshops are being arranged. For instance, Companies such as GCOML, SWAN, JIB, NASCO Foods, Coca-Cola, Integrated Dairies Ltd generally develop their own guidelines for training. The quantitative literature on sales force management has examined several methods by which sales force productivity can be increased. These include, but are not limited to, sales force compensation (Basu, Lal, Srinivasan and Staelin, 1986; Basu and Kalyanaram, 1990), sales force sizing (e.g., Lodish, Curtis, Ness and Simpson, 1988), call allocation (e.g., Lodish, 1971), territory design and alignment (Rangaswamy, Sinha and Zoltners, 1990; Skiera and Albers, 1998), and sales force benchmarking (Horsky and Nelson, 1996). Seemingly overlooked, however, has been the use of training as a means to increase the productivity of the sales force. This omission is surprising given that studies have consistently stressed that training is a prerequisite for successful selling (Churchill, Hartle and Walker, 1986). Training increases sales force productivity by giving salespeople the skills needed to perform their tasks effectively. For example, data from a Bell South video sales training program showed that training increased sales effectiveness by 50% (Martin and Collins, 1991). Training also increases profits by lowering the firm’s selling and supervision costs. A study of Nabisco’s sales training program by Klein (1997) found a $122 (N18, 300) increase in sales and a twenty-fold increase in profit for every dollar invested in training. Adept salespeople are particularly important for a firm to maintain its competitive edge in the face of keen competition (Ingram and LaFord, 1992). Today’s customers expect salespeople to have deep product knowledge, to add ideas to improve the customer’s operations, and to be efficient and reliable. These facts, highlights the crucial role of training sales force which brings about the profit maximization of the company. With this understanding in mind, it is very important to assess the training and sales force productivity in the Nigeria’s manufacturing industry. Statement of the Problem Sales teams are under constant pressure to meet customer expectations, while bringing in revenue for the company. As globalization brings the world closer together, these pressures increase. A recent Aberdeen survey revealed; companies that implement mobile sales force automation solutions are 1.5 times more likely to see an improvement in sales force productivity versus those that do not. Sales teams are looking at Mobile Sales Force Automation (SFA) technologies to arm their field representatives to be able to handle the ever increasing customer demands on a global basis.The challenge most companies face is that users are not fully utilizing or even using salesforce.com at all. They are noticing an increase in user resistance, not adoption, and what will be accomplished through sales training. When objectives are aligned with strategic organizational objectives and identified salesperson needs, deficiencies, requirements and competencies, then sales training is maximized (Attia et al., 2005). They further listed the sales training objectives derived from global/crosscultural research appearing over the past two decades to include: ? Improve sales force negotiation skills to increase successful sales encounters and longterm relationships for small/medium sized firms. ? Decrease sales training costs for local firms, improve sales force control for global companies, and improve customer relations and time management for both global and local firms. ? Improve sales force morale, sales routing, selling skills, market share, sales volume, and competitive position. ? Impart effective product, selling, intercultural skills, and increase salesperson knowledge about companies. ? Reduce turnover rates and increase salesperson motivation levels. ? Promote communication flow between parent companies and subsidiaries related to selling and compensation policies. ? Build customer information systems and databases, and disseminate parent companies market orientation practices. ? Improve salespersons’ negotiation skills, increase abilities to nurture and sustain longterm relationships and help evaluate performance (quantitative/qualitative) measures. Sales training program design and implementation Firms cautiously adapt and transfer training content and methods to locations within and abroad. For example, Geber (1989) recommended that global firms utilize local bi-cultural employees or consultants to identify gaps in training programs designed in the home country. Montago (1996), discussed how Korean trainers met with their U.S. managers and then modified the training concepts and ideas to address local cultural conditions. Jantan and Honeycutt (2002), reported that global firms in Malaysia translated training manuals, used joint headquarters/local trainers, and selected/integrated training methods to minimize cultural barriers. Also, different training methods were necessary to transfer salesperson negotiation skills/behaviors in northern European (UK, Netherlands, and Finland) and southern European (Spain and Portugal) countries because these two groups of nations exhibit distinct cultural characteristics (Roman and Ruiz, 2003). In Singapore for instance, local and global hotel training programs offered different program content, levels of demonstration, and inclass participation. Global firms also incorporated sales training into their strategic marketing plan (Honeycutt et al., 2005). Global firms’ sales managers in Malaysia, in contrast to their local counterparts, reported significant improvement in salespersons performance (sales presentation, communication, technical, and customer relations skills) after completing sales training (Jantan et al., 2004). Global companies employ a higher level of demonstration methods, while local firms use onthe-job (OJT) training methods (Honeycutt et al., 2005 and Jantan and Honeycutt, 2002). Empirical studies conducted in Saudi Arabia (Erffmeyer et al., 1993), Singapore (Honeycutt et al., 2005), Malaysia (Jantan and Honeycutt, 2002), and Slovakia (Honeycutt et al., 1999), reveal that the sales training content of global companies consistently focused on market and customer information, in contrast to product knowledge for local firms. Also, ethical sales issues were significantly more prevalent in global sales training programs in Singapore (Honeycutt et al., 2005). Other issues that can affect sales training program content and methods include: translation problems (Kallet, 1981 and Honeycutt et al., 1996), industry and corporate culture-related issues (Keater, 1994 and Keater, 1995), parent firm market orientation (Cavusgil, 1990; Erffmeyer et al., 1993 and Honeycutt et al., 1999), and technological capability (Flynn, 1987 and Zeira and Pazy, 1985). Additionally global companies, in contrast to local firms, devote greater resources – in the form of time, effort, and money – to train new sales representatives (Honeycutt et al., 2005; Jantan and Honeycutt, 2002 and Honeycutt et al., 1999). To minimize cultural mistakes, global firms do carefully select, adapt, and balance their training delivery methods across cultures. Market orientation and Critical sales skills Market orientation relates to the firm's desired level of company-wide concern and responsiveness to customer needs and competitive actions (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990 and Narver and Slater, 1990). The construct indicates the extent to which the marketing concept has been adopted as a business philosophy (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993). Market orientation can be considered as a set of behaviors, activities and cultural norms that emphasize customers, competitors, and strong inter-functional coordination (Brown et al., 2002; Hurley and Hult, 1998] and Zhao and Cavusgil, 2006). Interests in market orientation have moved increasingly from issues of definition and measurement to those of implementation, and particularly the link between market orientation and the attitudes and behaviors of people employed in the organization (Narver et al., 1998 and Piercy et al., 2002). In examining the impact of market orientation on the sales organization, Siguaw, Brown and Widing (1994), argued strongly that the firm-level behaviors incorporated in the market orientation construct indicate the level of meaningful support provided to salespeople. They argued for a strong correspondence between the market orientation desired as a firm level, and the market orientation displayed by the sales force. Certainly, market orientation has been associated with a number of positive salesperson attitudes and behaviors (Siguaw et al., 1994), and customer orientation has been widely considered as an important salesperson characteristic. However, while market orientation has been widely studied in the marketing literature, and to a lesser extent in prior sales research, we have been unable to locate any previous studies concerning the relationship between market orientation and sales management control. In particular, prior research does not appear to have examined the impact of market orientation on sales manager control priorities, behaviors and corresponding competencies. Nonetheless, prior research suggests the advantages of a strong linkage between sales management strategy and a company's overall competitive strategy (Olson, Cravens, and Slater, 2001), and a similar logic should apply to market orientation. Importantly, sales managers in different selling situations are likely to have different priorities regarding salespersons’ skills level (e.g. competence). Therefore, market oriented imperatives for the sales unit, in terms of the most important or critical salesperson skills should be associated with the sales manager's behavior control strategy. Accordingly, the skills/management control relationship considers how well sales manager control level corresponds to the salespersons’ skills level. If the importance of skills for the organization's selling situation is correctly assessed by the sales manager, and management control activities are consistent with salespeople's critical skills needs, then a positive control level relationship should be present. The higher the importance of sales skills required by the selling situation, the higher the level of behavior-based control will be. This should provide the manager with the basis to more effectively develop these skills in salespeople and then monitor their application by salespeople to the customer relationships for which they are responsible

Concept of Productivity

Webster’s Dictionary defines productivity as a state of yielding or furnishing results, benefits or profits. This definition may be intuitively appealing, but it is of little use to managers of economic activities since it overlooks the resources used to yield the results. Economists like Prokopenko (1987) and Garvin (1992), overcome this short coming by defining productivity as the ratio of output to input, or the results achieved per unit of resource; a measure of how effectively the resources are utilized. This entry emphasizes the roles of sales management in increasing the productivity of the sales force and the firm. There is an extensive body of literature covering techniques for measuring and improving sales force productivity (Poole and Warner, 2001). The aim of this entry is to provide an overview or conceptual framework to enable sales force as well as the firm and select the techniques to be used for its implementation. According to Lawlor (1985), the conceptual approach to improvement can help sales managers to focus on productivity program results instead of on program activities. If for instance, as a result of the program, the values of fixed and variable inputs are decreased and output is increased, the sales force and firm’s productivity must increase. Conversely, if the improvement program fails to achieve any of these results, it will be a failure regardless of the amount of enthusiasm and activity it generates among the sales force and within the firm. Garvin (1992), further opined that the approach also emphasized the need for developing adequate measures for evaluating the performance of improvement programs, measures that track reductions in variables and fixed inputs and increases in outputs to ensure actual productivity (i.e sales force) improvement.

Effects of Sales training on Sales force productivity

According to Honeycutt et al., 1993; Dubinsky, 1996), sales training typically has three stages: assessment (establishing training needs and objectives); training (selection of trainers, trainees, training facilities and methods, program content and implementation) and evaluation (assessment of program effectiveness). It involves the systematic attempt to describe, explain and transfer ?good selling practices? to salespeople (Leigh 1987). The most common sales training objective is to increase sales performance (ElAnsary, 1993; Honeycutt et al., 1993; Jackson and Hisrich, 1996; Churchill et al., 1986). Salespersons’ productivity represents behaviours that are evaluated in terms of their contributions to the goals of the organisation (Walker et al., 1979). Skill level is one of the antecedents of sales performance (Churchill et al., 1985; Sujan et al., 1988) and refers to the individual capacity to implement sales tasks (Leong et al., 1989). Research suggests that training may increase the salesperson’s knowledge base and skill level, resulting in higher productivity (Anderson et al., 1995). Also, findings from Ingram et al. (1992), suggest that the most significant factors contributing to salespeople’s failure can be addressed through training. Similarly, according to the results of Piercy et al. (2002), sales managers rated sales training as one of the most important factors in improving sales force performance as well as sales force productivity. From this point of view, training enhances learning so that salespeople reach more acceptable productivity levels in less time than learning through direct experience alone (Leigh, 1987). Results that partially agree with this influence have been found by Christiansen et al. (1996) in an exploratory study based on three companies gathering data from salespeople. In relating the above discussion to sales management research, several authors argue that sales training can be effective in achieving training objectives, the most common of which is geared towards increasing sales performance and sales force productivity (Donaldson, 1998), but only if managers have the appropriate attitudes towards involvement in the training.

METHODOLOGY

The study was undertaken to assess the impact of training on sales force productivity in Jos metropolis. It is simply because the services offered by sales force personnel in this very important sector have gone through varying degree of changes and sophistication in recent times. To achieve that, secondary source of data was used to obtain the information. Information about the cost of training sales force of Nasco Company and the profit realized for the periods between 2006 -2010 was used to analyze the data. From the data collected, the hypothesis formulated was tested using regression tool of analysis.

DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

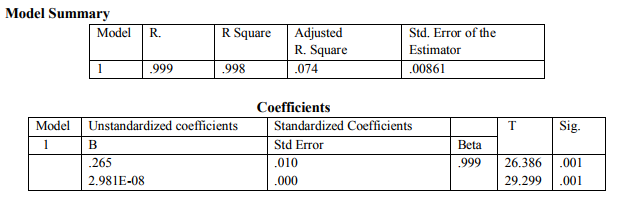

To ascertain whether or not there is a significant relationship between investment in sales force training and profit, regression statistical tool was employed. The SPSS package was used to analyze the data. The results are presented below: Predicators (Constant), INVESTMENT Dependent variables: PROFIT

Interpretation

R, which is 0.999 (coefficient of relationship) explains the strength of relationship between investment in training sales force and profit. This means that there is a strong positive relationship between the two variables. It therefore implies that if there is a significant drop in investment in sales force training, there will be a corresponding decrease in profit. R2 (coefficient of determination) measures forecasting power of the independent variable. Since R2 = 0.998, it means that about 99% of the total variation in y (profit) is accounted for by a 100% increase in x (investment in sales force training). The values of t – computed for both a and b which are 26. 386 and 29.299 respectively show that they are greater than the t – tabulated (1. 960). This suggests that null hypothesis be rejected. This implies that there is significant relationship between investment in sales force training and profit,

CONCLUSION

This research study was aimed at assessing the impact of training on sales force productivity in the Nigeria’s manufacturing industry, taking an empirical study of Nasco Company Ltd Jos. Overview of training, Assessing sales training needs,

Sales training objectives setting, Sales training program design and implementation, market orientation and critical sales skills, concept of productivity and sales training effects on sales force productivity were discussed. Furthermore, from the hypothesis tested, the result revealed that there is a significant relationship between investment in training and sales force productivity of Nasco Nigeria Ltd.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on our findings, we hereby advance the following recommendations:

I. Nasco Company should always remember to consider the potentials of its sales force at the organization, activity, and individual levels.

II. Rather than outsourcing the distribution of its products, Nasco Company should train its employees.

III. Since investment in training sales force enhances sales force productivity as well as company’s profit, the company under review and indeed other companies as well should invest more in the training of their sales force.

References:

1. Anderson, A. (1993). Successful training practice: A manager's guide to personnel development, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford.

2. Anderson, R.E., Hair, J. F. and Bush, A. J. (1995), Sales Management, 2nd ed., McGraw Hill, NewYork, NY

3. Attia, A., Honeycutt Jr. E. D. and Leach, M. (2005). A three-stage model for assessing and improving sales force training and development, Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 25(3).

4. Basu, A. K. and Kalyanaram, G. (1990). On the relative performance of linear versus nonlinear compensation plans. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 7(3).

5. Basu, A. K., Lal, R., Srinivasan, V. and Staelin, R. (1986). Sales force compensation plans: An agency theoretic perspective. Marketing Science, 4(4).

6. Baldauf, A., Cravens, D. W. and Piercy, N. F. (2005). Sales management control research — synthesis and an agenda for future research, Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 25 (1)

7. Brown, T. J., Mowen, J. C., Donavan, D. T. and Licata, J. W. (2002). The customer orientation of service workers: Personality trait effects on self- and supervisor performance ratings, Journal of Marketing Research 39 (1)

8. Cascio, Wayne F. (1989), Managing Human Resources, 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill 9. Cavusgil, S. T. (1990). The importance of distributor training at caterpillar, Industrial Marketing Management 19

10. Churchill, Jr., G. A., Hartley, S. W. and Walker, O. C. (1986). The determinants of salesperson performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 22.

11. Churchill, G.A., Ford, J., Hartley, S.W. and Walker, O. C. (1985), "The determinants of salespeople performance: a meta-analysis", Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 22.

12. Christiansen, T., Evans, K.R., Schlacter, J. L. and Wolfe, W.G. (1996), "Training differences between services and good firms: impact on performance, satisfaction, and commitment", Journal of Professional Services Marketing, Vol. 15 No.1

13. Dubinsky, A. J. (1996), "Some assumptions about the effectiveness of sales training", Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, Vol. 16 No.3.

14. Dubinsky, A. and Barry, T. (1982). A survey of sales management practices, Industrial Marketing Management 11

15. Dubinsky, A. J. (1996). Some assumptions about the effectiveness of sales training. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 16 (3).

16. El-Ansary, A. I. (1993), "Selling and sales management in action: sales force effectiveness research reveals new insights and reward-penalty patterns in sales force training", Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, Vol. 13

17. Erffmeyer, R., Russ, R., and Hair, J. F. (1991). Needs assessment and evaluation in sales training programs, Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 11 (1).

18. Erffmeyer, R. Russ, R., and Hair, J. F. (1992). Traditional and high-tech sales training methods, Industrial Marketing Management 21

19. Erffmeyer, R., Al-khatib, J. A., Al-Habib, M. I. and Hair, J. F. (1993). Sales training practices: A cross-national comparison, International Marketing Review 10 (1).

20. Flynn, B. H. (1987). The challenge of multinational sales training, Training and Development Journal 41

21. Galvin, T.(2001). Industry report, Training 38 (10)

22. Garvin ,D,(1992).Operations Strategy: Text and Cases, Eaglewood cliffs, NJ: Prentice Itall.

23. Geber, B. (1989). A global approach to training, Training

24. Hall, B. (2005), Sales training makeovers, trainingmag.com, accessed July 4, 2005.

25. Honeycutt, E.D., Howe, V., Ingram, T.N. (1993), "Shortcomings of sales training programmes" Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 22

26. Honeycutt, E. D. Ford, J. B. and Kurtzman, L. (1996). Potential problems and solutions when hiring and training worldwide sales teams, Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 11 (1)

27. Honeycutt, E. D., Ford, J. B., Lupton, R. and Flaherty, T. (1999).Selecting and training the international sales force: A comparison of China and Slovakia, Industrial Marketing Management 28.

28. Honeycutt, E. D., Mottner, S. and Z. Ahmed, Z. (2005). Sales training in a dynamic market: The Singapore service industry, Services Marketing Quarterly 26 (3).

29. Horsky, D., and Nelson, P. (1996). Evaluating sales force size and productivity through efficient frontier benchmarking. Marketing Science, 15(4).

30. Hurley, R. F. and G.T.M. Hult, G.T.M. (1998). Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: An integration and empirical examination, Journal of Marketing 62 (3)

31. Ingram, T. N. and R.W. LaForge, R. W. (1992). Sales management: Analysis and decision making (2nd ed.), Dryden, Fort Worth, TX.

32. Ingram, T. N., Schwepker, C. H., Hutson, D. (1992), "Why salespeople fail", Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 21.

33. Jackson, R. and Hisrich, R. (1996), Sales and Sales Management, Prentice Hall International Editions, London.

34. Jantan, M. A. and E.D. Honeycutt, E. D. (2002). Sales training practices in Malaysia, Multinational Business Review 10 (1).

35. Jantan, M.A., E. D. Honeycutt, E. D., Thelen, S. and Attia, A. (2004). Managerial perceptions of sales training and performance, Industrial Marketing Management 33 (7).

36. Jaworski, B. J. and Kohli, A. K. (1993). Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences, Journal of Marketing 57. 37. Kallet, M. W. (1981). Conducting international sales training, Training and Development Journal 35 (11).

38. Keater, M. (1994). Training the world to sell, Training. Vol. 56

39. Keater, M. (1995). International development, Training. Vol. 32

40. Kohli, A. K. and Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications, Journal of Marketing 54.

41. Klein, R. (1997). Nabisco sales soar after sales training. Marketing News, January 6, 23.

42. Lawlor, A. (1985). Productivity Improvement Manual, Wesport, CT: Quorum.

43. Learning International (1989). What Does Sales Force Turnover Cost You? Stanford, CT: Learning International, Inc 44. Leigh, T.W. (1987), "Cognitive selling scripts and sales training",Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management.

45. Leong, S., Busch, P.S., John, R. (1989), "Knowledge bases and salesperson effectiveness: a script-theoretic analysis", Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 26

46. Lodish (1971), CALLPLAN: An interactive salesman's call planning system, Management Science 18

47. Lodish, E. Curtis, M. Ness and M. K. Simpson (1988), Sales force sizing and deployment using a decision calculus model at Syntex laboratories, Interfaces 18

48. Martin, W. S., and Collins, B. H. (1991). Interactive video technology in sales training: A case study. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 11.

49. Montago, R. V. (1996). Integrated cross-cultural business training, Journal of Management Development 15 (4).

50. Narver, J. C., Slater, S.F. and Tietje, B. (1998). Creating a market orientation, Journal of MarketFocused Management 54

51. O’Connell, W. A. (1988). A 10-year report on sales force productivity. Sales and Marketing Management, 140(16).

52. Olson, E. M; Cravens, D. W. and Slater, S. F. (2001). Competitiveness and sales management: A marriage of strategies, Business Horizons

53. Pelham, A. (2002). An exploratory model and initial test of the influence of firm level consulting-oriented sales force programs on sales force performance, Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 22 (2).

54. Piercy, N. F., Craven, D. W. and Morgan, N. A. (1998). Sales force performance and behaviorbased management processes in business to business sales organizations, European Journal of Marketing 32.

55. Piercy, M. F. Harris, L. C. and Lane, N. (2002). Market orientation and retail operatives' expectations, Journal of Business Research 55

56. Pinkowitz, W. H; Moskal, J. and Green, G. (1997). How much does your employee turnover cost? Small Business Forum 14

57. Prokopenko, J. (1987). Productivity Management: A practical Handbook, Geneva: International Labour Office.

58. Rangaswamy, A; Sinha, P. and A. Zoltners, A. (1990). An integrated model-based approach for sales force structuring, Marketing Science 9 (4)

59. Richardson, R. (1999). Measuring the impact of turnover on sales. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 19

60. Roman, S. and Ruiz, S. (2003). A comparative analysis of sales training in Europe: Implications for international sales negotiations, International Marketing Review 20 (3)

61. Skiera, B., and Albers, S. (1998). COSTA: Contribution maximizing sales territory alignment. Marketing Science, 17(3).

62. Siguaw, J. A. Brown, G. Widing, R. E. (1994). The influence of the market orientation of the firm on sales force behavior and attitudes, Journal of Marketing Research 31 (1994, February)

63. Sujan, H., Sujan, M., Bettman, J.R. (1988), "Knowledge structure differences between more effective and less effective salespeople", Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 25

64. Walker, O.C., Churchill, G.A., Ford, N.M. (1979). "Where do we go from here? Some selected conceptual and empirical issues concerning the motivation and performance of industrial salesforce", in Albaum, G., Churchill, G.A. (Eds),Critical Issues in Sales Management: State of the Art and Future Research Needs.

65. Wilson, P., Phillip, Strutton, Farris; Strutton, D. and Farris, M. T. (2002). Investigating the perceptual aspect of sales training, Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 22 (2)

66. Zeira, Y. and Pazy, Y. (1985). Crossing national borders to get trained, Training and Development Journal (November 1985).

67. Zhao, Y. and Cavusgil, S. T. (2006). The effect of a supplier's market orientation on manufacturer's trust, Industrial Marketing Management 35

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License