IJCRR - 5(6), March, 2013

Pages: 92-97

Date of Publication: 30-Mar-2013

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND AETIOLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS OF KERATOMYCOSIS IN A TERTIARY CARE HOSPITAL IN NORTH KARNATAKA

Author: Sathyanarayan M.S., Suresh B. Sonth, Surekha Y.A., Mariraj J., Krishna S.

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Introduction: Keratomycosis is a common cause of corneal blindness and requires prompt diagnosis for early initiation of antifungal treatment. The present study was undertaken to determine the epidemiological features associated with laboratory confirmed cases of keratomycosis, to compare the direct microscopy and culture in the diagnosis of keratomycosis and to determine the pattern of fungal isolates in these cases. Research Methodology: Epidemiological data of 87 suspected keratomycosis cases over a period of one year from July 2009 to June 2010 was noted and the cases were investigated for evidence of fungal pathogens in corneal scrapings by direct microscopy using 10% Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) preparation, Gram stain and fungal culture as per standard protocols. Results: A majority of the 34 laboratory confirmed cases were noted in the rural population, with a male predominance and mostly in the age group associated with outdoor activity. KOH preparation was found to be most sensitive (82.35%) among the techniques studied. Aspergillus spp. were the commonest isolates (69.56%) encountered. Conclusion: Rural population, especially males in the active working age group and those involved in agriculture were found to be predisposed to the development of fungal corneal ulcers. Rapid and reliable detection of presence of fungal elements in suspected cases of keratomycosis can be done using direct microscopy with KOH preparations of corneal scrapings. Aspergillus spp. were found to be the commonest isolates, followed by Fusarium spp. and dematiaceous fungi in patients presenting with keratomycosis in Bellary.

Keywords: Keratomycosis, KOH preparation, Gram stain, Culture, Aspergillus spp.

Full Text:

INTRODUCTION

The term ‘keratomycosis’ refers to invasive infection of corneal stroma caused by a variety of fungal species and is frequently encountered in many tropical countries including India and is a significant cause of infective monocular blindness. The precipitating event for fungal keratitis is often trauma with a vegetable / organic matter, seen mostly in agricultural workers. Implantation of fungus directly in the cornea by trauma leads to slow growth and proliferation to involve the anterior and posterior stromal layers. The fungus can penetrate the descemet's membrane and pass into the anterior chamber. The patients present a few days or weeks later with fungal keratitis. Keratomycosis is reported to be very common, representing 40%-50% of all cases of culture-positive infectious keratitis in India.1,2 Fungi have been reported as the commonest isolates in studies of microbial keratitis from South India.3,4 Bellary is a district in North Karnataka region in southern part of Indian subcontinent with a predominant agriculture based rural population. The study was intended to determine the epidemiological factors and to compare microscopic techniques with culture for the diagnosis of keratomycosis. The present study was undertaken in the department of microbiology to determine the epidemiological features in patients with confirmed keratomycosis, to compare direct microscopy using 10% KOH preparation, Gram stain and Culture on Sabouraud’s Dextrose Agar (SDA) in the diagnosis of keratomycosis and also to study the pattern of isolation of fungal pathogens in cases of keratomycosis among patients attending the tertiary care hospital attached to Vijayanagar Institute of Medical Sciences (VIMS), Bellary, Karnataka.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective study was carried out over a period of one year from July 2009 to June 2010. Patients presenting with clinically suspected fungal corneal ulcers with signs and symptoms of inflammation with or without hypopyon were included in this study. Patients presenting with suspected or confirmed viral keratitis, bacterial keratitis, interstitial keratitis, sterile neurotropic ulcers and ulcers associated with autoimmune conditions were excluded from the study.5 The clinical history and epidemiological data of the patients included in the study were noted. Corneal scrapings were collected for direct microscopic examination and fungal culture after, performing a detailed ocular examination and clinical diagnosis of keratomycosis as per standard protocol. A total of 86 specimens of corneal scrapings from 48 male and 38 female patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were collected using standard techniques and processed for direct microscopy using 10% KOH preparation, Gram stain and culture on SDA in the mycology section of the department of microbiology, VIMS, Bellary during the study period. A stained smear or wet mount using 10% KOH preparation was considered positive for fungus if one or more fungal filament was seen on the entire slide and the findings correlated with the clinical condition. The scrapings from the corneal ulcers were inoculated directly onto Sabouraud’s dextrose agar with antibiotics but without cycloheximide as per standard protocols. The material was directly inoculated onto the surface of solid media in a row of c-shaped streaks, incubated at 25°C and 37oC for a period of three weeks; the plates were examined daily during the first week and twice weekly during the next two weeks. The isolate was considered to be significant if it was consistent with the clinical signs, growth occurred on the ‘c’ streak, smear results were consistent with culture and the same organism showed growth on more than one media.2,5,6 The mycelial isolates were identified by their colony characteristics on SDA plates, microscopic morphology on lactophenol cotton blue (LPCB) mount and slide culture as per standard mycological guidelines. The culture was considered as sterile if no growth was observed even after four weeks of incubation.2,5 A definitive case of keratomycosis was considered when fungal elements were detected by microscopic methods or culture on SDA yielded a fungal isolate and the finding was consistent with the clinical condition of the patients.

STATISTICAL METHODS

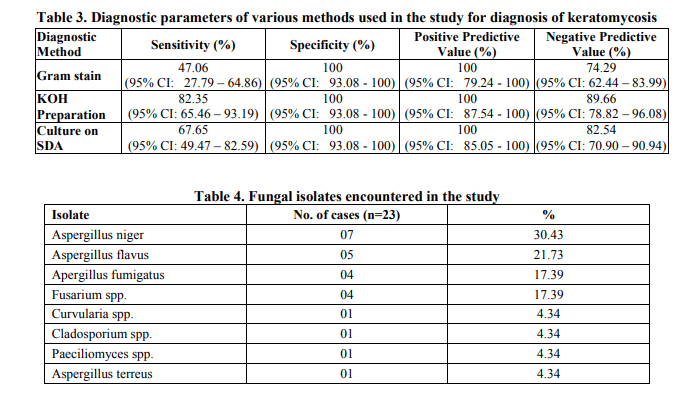

Diagnostic parameters like Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), Negative Predictive Value (NPV) of the three diagnostic methods were calculated using standard formulae.

RESULTS

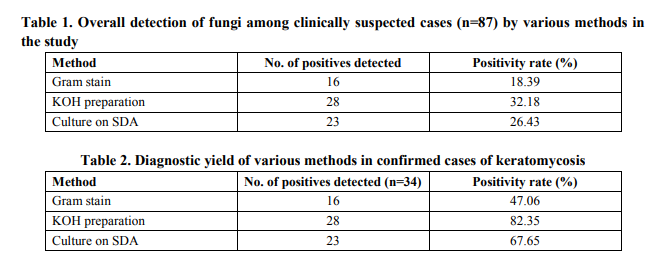

A total of 34 cases (39.08%) were confirmed as keratomycosis in the present study by correlating the laboratory and clinical findings. Males were predominantly affected by keratomycosis as compared to females in the present study- 20 males and 14 females (Male: Female ratio- 1.7:1). Mean age of occurrence of keratomycosis was 46.44 years. Maximum number of keratomycosis cases was encountered in the age groups of 41 – 60 (13/34 cases), followed closely by the age group of 21 – 40 (12/34 cases). No cases were detected in cases in patients below 20 years of age. 18 of the 34 confirmed cases were found to be involved in agricultural occupation (52.94%), 26 of the 34 cases (76.47%) were from a rural area and 19 of them had history of corneal trauma (55.88%). Fungal elements were identified by microscopy by Gram stain in 16 cases, KOH mount in 28 cases and 23 cultures grew fungal isolates on SDA and fulfilled the criteria of being pathogens (Table 1 and 2). All Gram stain positive smears were found to be positive by KOH mount. 11 cases were positive only by KOH preparation and 6 cases were only positive on culture. Thus, Gram stain and KOH mount were found to be sensitive in 69.56% and 73.91% of culture proven keratomycosis cases respectively. Among the techniques studied, the sensitivity of KOH preparation was found to be higher than culture and Gram stain in laboratory confirmed cases of keratomycosis (Table 3). Of the 23 fungal isolates, Aspergillus spp. were the commonest isolates (16/23 isolates- 69.56%), Aspergillus niger being the commonest pathogen isolated in 7 cases, followed by Fusarium spp., and dematiaceous fungi. (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Fungal infections of the cornea are important causes for monocular blindness, being mainly prevalent in tropical countries and regularly reported from South India.3,4 Fungal infections of the cornea are commoner in persons involved in agricultural occupation. Early diagnosis of cases of keratomycosis is essential to initiate antifungal therapy and to prevent complications including corneal blindness. The incidence of 39.08% of fungal aetiology noted in the present study compares with the findings of other studies.5,7 The mean age of occurrence of keratomycosis in the present study was found to be 46.44 years and the pattern of age distribution of cases encountered showed a majority of the cases being reported in the 21 – 60 years age group reflecting the active working period of life with a higher incidence in those over 40 years of age, exposing them to risk of developing keratomycosis. A majority of the cases noted were from rural areas and in those involved in agriculture. These are comparable to the findings in the studies of J.Chander et al and Parmjeet Kaur Gill et al.5,7 20 of the 34 confirmed cases (58.82%) were in males in the present study which is comparable to the study of Tahereh Shokohi et al.8 Various modalities are available for diagnosis of the condition, but the lack of infrastructure in many laboratories especially in developing countries act as an impediment for the diagnosis. Direct microscopy using a 10% KOH preparation is a technique which can be easily followed even in resource poor settings. The sensitivity of KOH preparations in detecting fungal elements in corneal scrapings have been reported to be high and these preparations have been useful in confirming a diagnosis of fungal keratitis in clinically suspected cases even when the cultures were negative.9 Other microscopic techniques using Calcofluor white (CFW) and its modifications like KOH + CFW preparations have been reported to have higher positive microscopic yield as compared to conventional KOH preparations. However, these methods require the availability of fluorescent microscope. Recent advances include Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), Confocal microscopy, Immunofluorescence staining etc.2,10 Gram stain among other stained preparations has been evaluated by various researchers earlier and in the present study lacks sensitivity and hence can result in underreporting of cases of keratomycosis. Isolation is considered as a definitive method of diagnosis of keratomycosis. Culture on SDA was considered as gold standard in many studies.11 However, reports suggest that direct microscopy from the corneal scrapings by KOH preparation can reveal more cases than culture on SDA when microscopic findings are correlated with clinical presentation.12 Agricultural occupation which has been identified as the major risk factor in the present study for keratomycosis has been reported in a number of studies. 5,7 The sensitivity of KOH preparation in confirming the diagnosis of keratomycosis was determined to be 82.35% overall (28/34 cases) and 73.91% among culture positive cases (17/23 cases) in the present study, while that of Gram stain was 47.06% overall and 69.56% among culture positive cases. These findings are comparable to the reports of Jagdish Chander et al and Tahereh Shokohi et al.5,8 The absence of growth on culture in cases where the direct microscopy was positive could be the administration of topical antifungal agents or steroids prior to collection of corneal scrapings. Aspergillus spp. have been reported as the leading cause of keratomycosis in the Indian subcontinent by various authors. 5,6,13,14 The pattern of isolation in the present study is comparable to the report of J. Chander et al. and Samar Basak et al.5,15

CONCLUSIONS

Keratomycosis is commoner in the active working age group, presenting mostly among patients from a rural background with agricultural occupation and exhibits a male predominance. Early diagnosis of the condition is imperative for initiation of antifungal therapy and to prevent blindness. KOH preparation is a simple, rapid and less labour intensive method with reliable sensitivity which can be used for confirming the diagnosis of keratomycosis. Identification of fungal elements in direct microscopy using 10% KOH preparation of corneal scrapings and isolation of fungal pathogens on SDA and correlation with clinical findings are recommended as confirmatory for the diagnosis of keratomycosis. Aspergillus species were the commonest causative fungi, followed by Fusarium spp. and dematiaceous fungi in keratomycosis in the present study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their deep gratitude to the faculty of the departments of ophthalmology and microbiology, VIMS, Bellary for their valuable help in collection and processing of clinical specimens from patients with clinical suspicion of keratomycosis for the study. Authors acknowledge the great help received from the scholars whose articles cited and included in references of this manuscript. The authors are also grateful to authors / editors / publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed. Authors are grateful to IJCRR editorial board members and IJCRR team of reviewers who have helped to bring quality to this manuscript.

References:

1. Agarwal V, Biswas J, Madhavan HN et al. Current perspectives in infectious keratitis. Indian J Ophthalmol 1994; 42: 171-92.

2. Nayak N. Fungal infections of the eye: laboratory diagnosis and treatment. Nepal Med Coll J. 2008;10:48–63.

3. Thomas PA, Kaliamurthy J, Geraldine P. Epidemiological and microbiological diagnosis of suppurative keratitis in gangetic West Bengal, Eastern India. Indian J Ophthalmol 2005;53:143.

4. Srinivasan M, Gonzales CA, George C, Cevallos V, Mascarenhas JM, Asokan B, et al. Epidemiology and aetiological diagnosis of corneal ulceration in Madurai, south India. Br J Ophthalmol 1997; 8: 965-71.

5. Chander J, Singla N et al. Keratomycosis in and around Chandigarh. A five-year study from North Indian tertiary care hospital. Indian J Path Microbiol 2008; 51 (2): 304-6.

6. Chowdhary A, Singh K. Spectrum of fungal keratitis in North India. Cornea 2005; 24: 8- 15.

7. Parmjeet Kaur Gill, Pushpa Devi. Keratomycosis- A retrosprective study from a North Indian tertiary care institute. JIACM 2011; 12(4): 271-3.

8. T. Shokohi, K. Nowroozpoor-Dailami, T. Moaddel-Haghighi. Fungal keratitis in patients with corneal ulcer in Sari, Northern Iran. Arch Iranian Med 2006; 9 (3):222 – 227.

9. Vajpayee RB, Angra SK, Sandramouli S, Honavar SG, Chhabra VK. Laboratory diagnosis of keratomycosis: Comparative evaluation of direct microscopy and culture results. Ann Ophthalmol 1993; 25: 68-71.

10. Rajeev Sudan, Yog Raj Sharma. Keratomycosis: Clinical diagnosis, Medical and Surgical Treatment. JK Science 2003; 5(1): 3-10.

11. A Laila, Salam MA, B Nurjahan, R Inthekhab, I Sofikul, A Iftikhar. Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) wet preparation for the Laboratory Diagnosis of Suppurative Corneal Ulcer. Bangladesh Journal of Medical Science 2010; 9(1): 27-32.

12. Sharma S, Garg P, Gopinathan U, Athmanathan S, Garg P, Rao GN. Evaluation of corneal scraping smear methods in the diagnosis of bacterial and fungal keratitis: A survey of eight years of laboratory experience. Cornea 2002; 21: 643-647.

13. Venugopal PL. Venugopal TL. Gomathi A, Ramakrishnan S. Ilavarasi S. Mycotic keratitis in Madras. lnd J Pathol Microbiol 1989: 32: 190-97.

14. Chander J, Sharma A. Prevalence of fungal corneal ulcers in Northern India. Infection.1994;22:207-09.

15. Basak SK, Basak S, Mohanta A, Bhowmick A. Epidemiological and microbiological diagnosis of suppurative keratitis in Gangetic West Bengal, eastern India. Indian J Ophthalmol 2005; 53 : 17-22.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License