IJCRR - Vol 09 issue 10 current issue , May, 2017

Pages: 28-31

Date of Publication: 27-May-2017

Print Article

Download XML Download PDF

The Incidence of Heparin Induced Thrombocytopenia in Orthopedic Surgery Patients in Khartoum, Sudan

Author: Amar Ibrahim Omer Yahia, Maria Mohamed Hamad Satti

Category: Healthcare

Abstract:Aim: The aim of this study was to determine the incidence of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) induced thrombocytopenia in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery in Khartoum Teaching Hospital. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a complication of heparin therapy in which the platelet count falls by 50% or more of the baseline value, or falls to below 150×109/L.

Methodology: This is a prospective cross sectional study carried out in Khartoum Teaching Hospital, Department of Orthopedic Surgery in the period between April-July 2013.

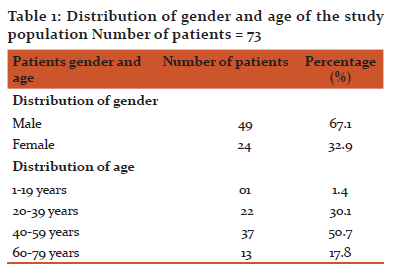

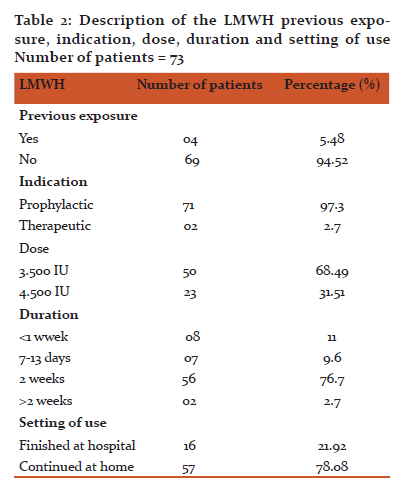

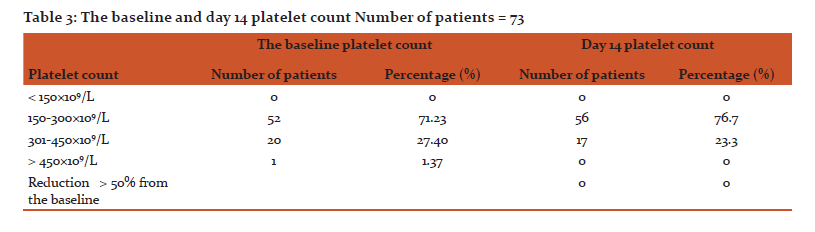

Results: Seventy three patients were included, forty nine (67.1%) were males and 24 (32.9%) were females. Most of the patients were between 40-59 years of age (50.7%). Sixty nine (94.52%) of the patients were not exposed to heparin before. All patients received LMWH as prophylaxis except 2 patients who received it for treatment. Fifty patients (68.49%) received LMWH in a dose of 3500 (IU) per day while 23 patients (31.51%) received it in a dose of 4500 IU. Fifty six of the patients received LMWH for 2 weeks, 15 patients for less than 2 weeks while 2 patients for more than 2 weeks. All patients had a baseline platelet count equal or more than 150×109/L. On day 14, none of the patients had 50% reduction or more in the platelet count from the baseline or a platelet count of less than 150×109/L.

Conclusion: The study found that no patient treated with LMWH had significant HIT.

Keywords: Low molecular weight heparin, Khartoum teaching hospital, Baseline platelet count

Full Text:

Introduction

Heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a complication of heparin therapy in which the platelet count falls by 50% or more from the patients baseline platelet count, or falls to below 150×109/L, and it may associated with increased incidence of arterial and/or venous thromboembolic complications [1]. Most often thrombocytopenia with or without thrombosis is seen. The presence platelet factor 4 /heparin-dependent immunoglobulin G antibodies can be implicated, so HIT is considered as a clinicopathologic syndrome since both clinical and laboratory features are important [2, 3]. HIT is around 10 fold less common with low molecular weight heparin preparations (LMWH) than with unfractionated heparin (UFH) [4]. Heparin is a drug widely used for thromboprophylaxis or treatment in many clinical conditions, including cardiovascular surgery and invasive procedures, acute coronary syndromes, venous thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, peripheral occlusive disease, dialysis and during extracorporeal circulation [5, 6]. Unfortunately, it can cause serious adverse effects, such as HIT which is a common, serious and potentially life-threatening condition [2, 7-9]. The majority of patients have type I HIT which appears to result from non immunologic activation of platelets [10] resulting in platelet aggregation due to heparin itself [11]. Type I HIT is relatively mild (platelet count >100×109/L), and has no adverse clinical consequences, even if the heparin is continued and usually resolves spontaneously [10]. Type II HIT occurs in 3 to 5% of patients receiving UFH, it is less common in patients receiving LMWH (< 1%). It is caused by an immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody that reacts with a complex of heparin bound to platelet factor 4 (PF4), results in platelet activation and endothelial cells injury. Type II HIT usually occurs after 5 to 14 days of heparin exposure. The platelet count is typically 50 to70×109/L, with a 50% (or more) drop in the platelet count from the baseline value [10]. Thrombotic events in type II HIT can include deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, arterial or venous gangrene of limbs, myocardial infarcts and strokes, and skin necrosis [10]. The apparent range in frequency of HIT was ranges from common (1%) in postoperative orthopedic and cardiac surgery patients receiving heparin for 1–2 week, to infrequent (0.1–1%) in medical patients receiving UFH or surgical patients receiving LMWH to rare (<0.1%) in medical and obstetrical patients receiving LMWH [12]. Some prospective studies suggest that the incidence of thrombosis is between 35 and 58 % in patients with documented HIT [13-15]. HIT often remains unrecognized with high risk of death from associated venous or arterial thrombosis [4], so the clinical and laboratory recognition is essential in order to stop heparin use immediately and commence an alternative anticoagulant. It`s incidence has not been studied in this country. The purpose of this study was to prospectively determine the incidence of HIT in Sudanese orthopedic patients treated with LMWH.

Materials and Methods

This is a prospective cross sectional study carried out in Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Khartoum Teaching Hospital, Sudan, in the period between April-July 2013. Seventy three patients who had orthopedic surgery and received low molecular weight heparin were included. HIT was defined as a complication of heparin therapy in which the platelet count falls by 50% or more from the patients baseline platelet count, or falls to below 150×109/L, and it may be associated with increased incidence of arterial and/or venous thromboembolic complications [1]. Exclusion criteria were the age group below one year and above eighty year, patients who had a low baseline platelet count, patients who were transfused with platelets or whole blood in the previous three months, patients on drugs known to cause thrombocytopenia or patients with co morbidity. Clinical data were recorded and platelet count were done as base-line (pre heparin administration), and at day 14 from s.c. heparin administration. Heparin was usually started on the first postoperative day but sometimes it was started before surgery and continued until discharge or full mobilization in all patients. 68.49% of the cases received LMWH in a dose of 3.500 IU while 31.51% of the patients received LMWH in a dose of 4.500 IU. Although 2 different LMWH preparations were used, we analyzed all the data as one group. The platelet count was obtained from complete blood counts (CBC) performed on an automated hematology analyzer, sysmex (model KX-21N), using well mixed whole blood collected in the ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) container and Blood samples were processed within two hours of collection. Peripheral blood films were stained with Leishman stain and examined using × 40 microscope lens to check the platelet count. The data were analyzed by statistical package for social science (SPSS) analytical system. This study was conducted after an informed consent was obtained from all patients (or parent or guardian for incapable participants).

Results

Out of 73 cases studied, 49 (67.1%) were males and 24 (32.9%) were females (Table 1). The distributions of the patients within the age groups were 50.7%, 30.1%, 17.8% and 1.4% for age group 40-59, 20-39, 60-79 and 1-19 years respectively (Table 1). Most patients were not exposed to heparin before, representing 69 patients (94.52%) and only 4 patients received heparin before (Table. 2). All patients received LMWH as prophylaxis except 2 patients received LMWH for treatment of a postoperative deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (Table. 2). Fifty cases (68.49%) received LMWH in a dose of 3.500 IU while 23patients (31.51%) received LMWH in a dose of 4.500 IU (Table. 2). The duration of heparin therapy was 2 weeks in 56 of cases (76.7%), less than 2 weeks in 15 cases (20.6) and more than 2 weeks in only 2 patients (2.7%), (for 17 days and 3 weeks respectively) (Table. 2). All patients started treatment in the hospital, 16 patients (21.92%) finished their treatment on discharge while 57 patients (78.08%) continued the treatment at home for 2 weeks except for 2 patients who had received it for more than 2 weeks (Table. 2). Baseline platelet count was between 150-300×109/L in 52 patients (71.23%), between 301-450 ×109/L in 20 patients (27.40) and in only one patient (1.37%) it was more than 450×109/L (Table. 3). On day 14, none of the patients had a ≥ 50% reduction in the platelets count from the base line or a platelets count of less than 150×109/L (in other words none of patients who received LMWH had HIT) (Table. 3).

Discussion

The incidence of HIT was studied in 73 patients who received LMWH for Prophylaxis or treatment of thrombosis in patients who underwent orthopedic surgery.

In this study, baseline platelet counts were obtained for all patients, in addition, platelets count on day 14 were carried out using an automated blood cell counter – sysmex (model KX-21N).

In conclusion, our data indicate that no patient treated with LMWH had HIT. These results are consistent with previous studies in international literature, in which platelet counts have been monitored in several large clinical trials that compared UFH with LMWH as antithrombotic prophylaxis after hip surgery or for the treatment of deep venous thrombosis [16]. The investigators found that HIT occurred in 2 out of 199 patients (1.0%) who received UFH after hip-replacement surgery, as compared with none of 198 patients who received LMWH; both patients with thrombocytopenia also had proximal deep venous thrombosis [17].

Our study confirms that HIT is rare with LMWH, this indicates that it is safe to use without a need for monitoring platelet count. Compared to UFH, LMWH has certain advantages, there is no need for anticoagulant monitoring, greater therapeutic index (less risk of bleeding for a given antithrombotic effect) and less chance for development of osteoporosis and HIT. In spite of the relatively high cost, the lower risk of immune sensitization and correspondingly lower risk of HIT and associated thrombotic events are important advantages of LMWH over UFH. UFH therapy is monitored by laboratory tests with consequent costs. Timing of sample collection and interpretation of results need experience in this field, which add to the disadvantages of using UFH. In addition to that, avoidance of difficulty associated with the diagnosis of HIT is the important factor for the use of LMWH, since the diagnosis of HIT depends on the clinical suspicion and can therefore be overlooked with grave consequences to the patient. The diagnosis of HIT is supported by screening laboratory testing and finally confirmed by functional assay by either heparin-induced platelet aggregation (HIPA) or serotonin release assay (SRA) which measure serotonin release from platelets induced by HIT antibodies and heparin. Or immunoassay such as enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA) to detect the HIT antibody that binds to the PF4/heparin complex [8, 9]. These confirmatory tests need to be made available. Another complication of long term heparin therapy is osteoporosis. This is much less with LMWH than UFH. This is especially important in women especially during pregnancy. This is another important advantage of LMWH and therefore it should be used more widely and be made available for a lower cost. However, a large number of patients cannot afford LMWH and are treated with UFH, so that the incidence of HIT in this category of patients needs to be studied.

Conclusion:

The study found that no patient treated with LMWH had significant HIT. These results are consistent with previous studies in international literature. This result indicates that the lower risk of immune sensitization and correspondingly lower risk of HIT and associated thrombotic events with use of LMWH.

Acknowledgement

Authors acknowledge the immense help received from the scholars whose articles are cited and included in references of this manuscript. The authors are also grateful to authors / editors / publishers of all those articles, journals and books from where the literature for this article has been reviewed and discussed. The authors are also thankful to all participating staff for their valuable role of this study and great thanks to the patients involved in this study for their unlimited Cooperation.

Funding

Nil.

Conflict of interest

Nil.

Authorship Contributions

AIOY designed the study, provided the cases, obtained clinical data and performed the platelets count. AIOY and MMHS were contributed together in reviewing the peripheral blood slides, interpretation of the results, statistical analysis and preparation of the manuscript.

References:

1. Kaushansky K, Lichtman MA, Beutler E, et al. Williams Hematology. 8th ed. China: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2010. P. 2685.

2. Warkentin TE. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: pathogenesis and management. Br J Haematol 2003; 121:535–555.

3. Warkentin TE. Platelet count monitoring and laboratory testing for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: recommendations of the College of American Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002; 126:1415–1423.

4. Hoffbrand AV, Catovsky D, Tuddenham EGD, et al. Acquired Venous Thrombosis. In: Hunt BJ, Greaves M. Post graduate Haematology. 6th ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. P. 891.

5. Chong BH: Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. J Thromb Haemost 2003; 1:1471-1478.

6. Jang I-K, Hursting HJ: When heparins promote thrombosis. Review of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Circulation 2005; 111:2671-2683.

7. Warkentin TE: Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Diagnosis and management. Circulation 2004; 110:e454-458.

8. Cines DB, Bussel JB, McMillan RB, et al: Congenital and acquired thrombocytopenia. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program) 2004; 390-406.

9. Warkentin TE, Greinacher A: Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: recognition, treatment, and prevention: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest 2004; 126(3 Suppl): 311S-337S.

10. Kern W. PDQ HEMATOLOGY. 1st ed. US: 1-55009-176-x; 2002. P.197-210.

11. Beck N, Diagnostic Hematology. 1st ed. London: Springer; 2009. P.275.

12. Lee DH, Warkentin TE. Frequency of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. In:Warkentin TE, Greinacher A, eds. In: Heparin-induced Thrombocytopenia, 3rd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., 2004:107–148.

13. Warkentin TE, Levine MN, Hirsh J, et al: Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in patients treated with low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparin. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:1330.

14. Greinacher A, Eichler P, Lubenow N, et al: Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with thromboembolic complications: Meta-analysis of 2 prospective trials to assess the value of parenteral treatment with lepirudin and its therapeutic aPTT range. Blood 2000; 96:846.

15. Wallis DE, Workman DL, Lewis BE, et al: Failure of early heparin cessation as treatment for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Am J Med1999; 106:629.

16. Colwell CW Jr, Spiro TE, Trowbridge AA, et al. Use of enoxaparin, a lowmolecular-weight heparin, and unfractionated heparin for the prevention of Deep venous thrombosis after elective hip replacement: a clinical trial comparing efficacy and safety. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:3-14.

17. Leyvraz PF, Bachmann F, Hoek J, et al. Prevention of deep vein thrombosis after hip replacement: randomised comparison between unfractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparin. BMJ 1991;303:543-8.

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License